Julia Ibbini is a visual and mixed media artist of Jordanian and British heritage. Based in Abu Dhabi, she is the founder of Studio Ibbini, an award-winning studio that creates work that intersects between contemporary art, design, and engineering. Studio Ibbini's work revolves around the themes of identity, place, and belonging.

Julia’s work has been showcased in the region and across the world including Art Basel Miami and Sharjah Islamic Arts Festival. In 2017, she was named the second-place winner of Delusional: Jonathan LeVine’s Search for the Next Great Artist and then in 2019 she was awarded the prestigious Van Cleef and Arpels Middle East Design Prize.

Saira Malik (S.M.): You are now a full-time visual artist and a designer but before this you had a career in marketing. What is your background in and how did you switch to this field?

Julia Ibbini (J.I.): Art has always been with me, even from very early childhood. Wanting to be an artist and having the courage to actually make it happen are two different things though. I didn't really commit to an artist practice until I was in my late 20s, and it took many years before I was able to become a full-time artist. I worked in marketing for over a decade after leaving university and while it was good work and great life experience, I was quite unhappy for much of the time, as if a piece of my life was missing. Leaving a stable corporate career was a scary process and being in a creative field has endless challenges but I’m always grateful to be where I am today.

(S.M.): How would you describe your work?

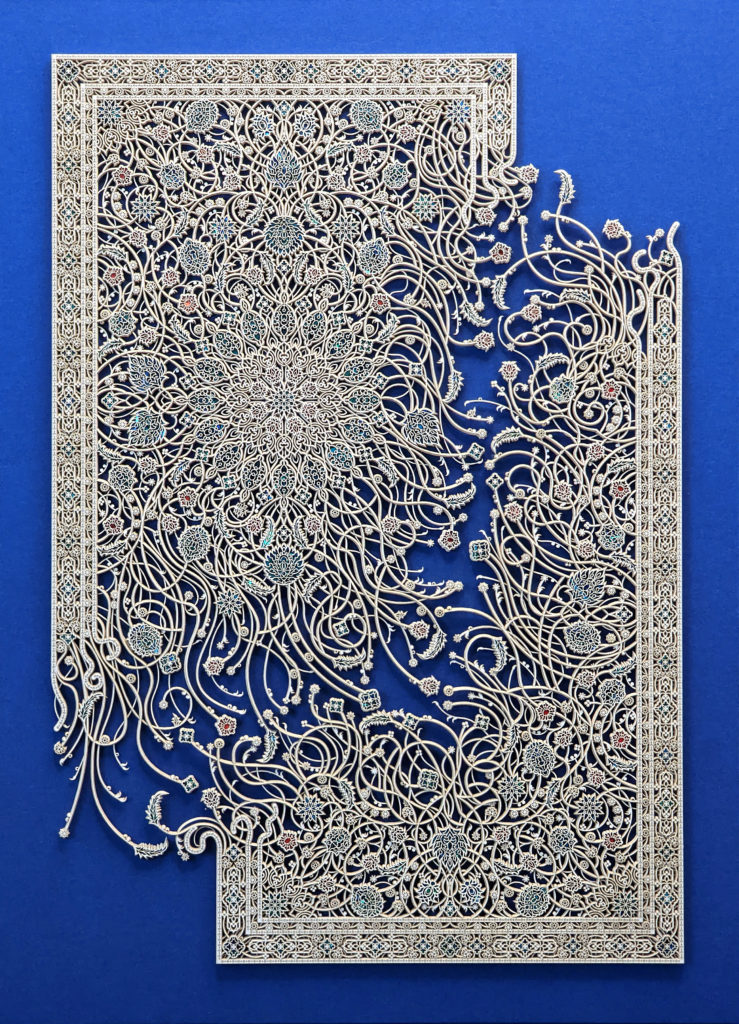

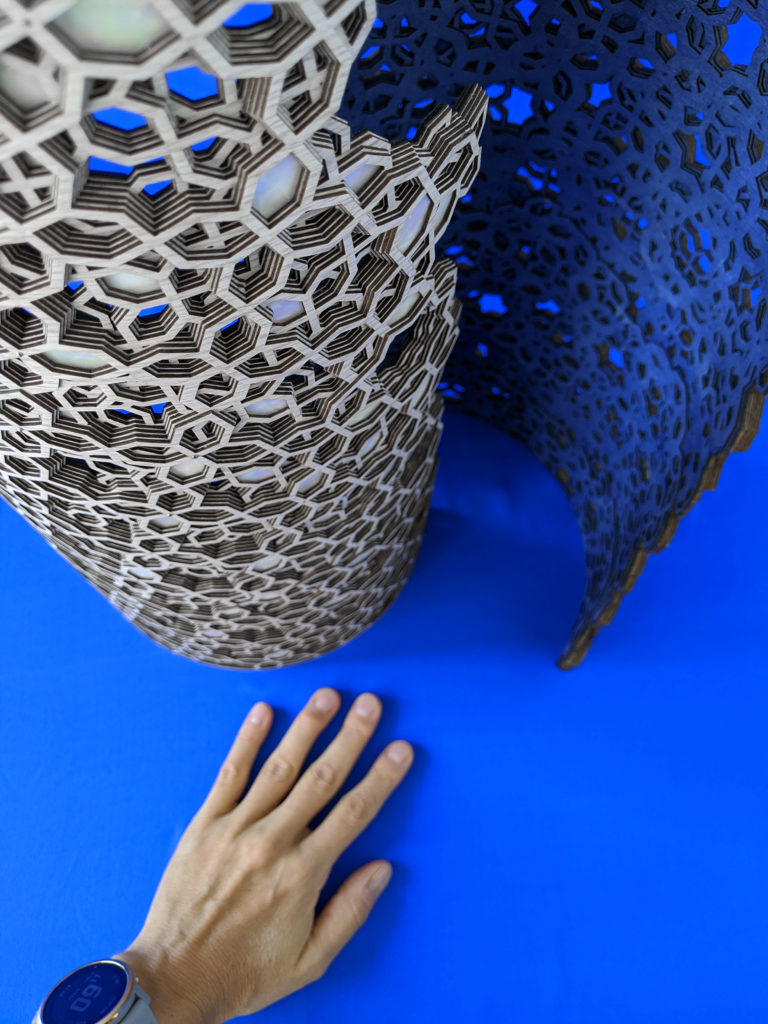

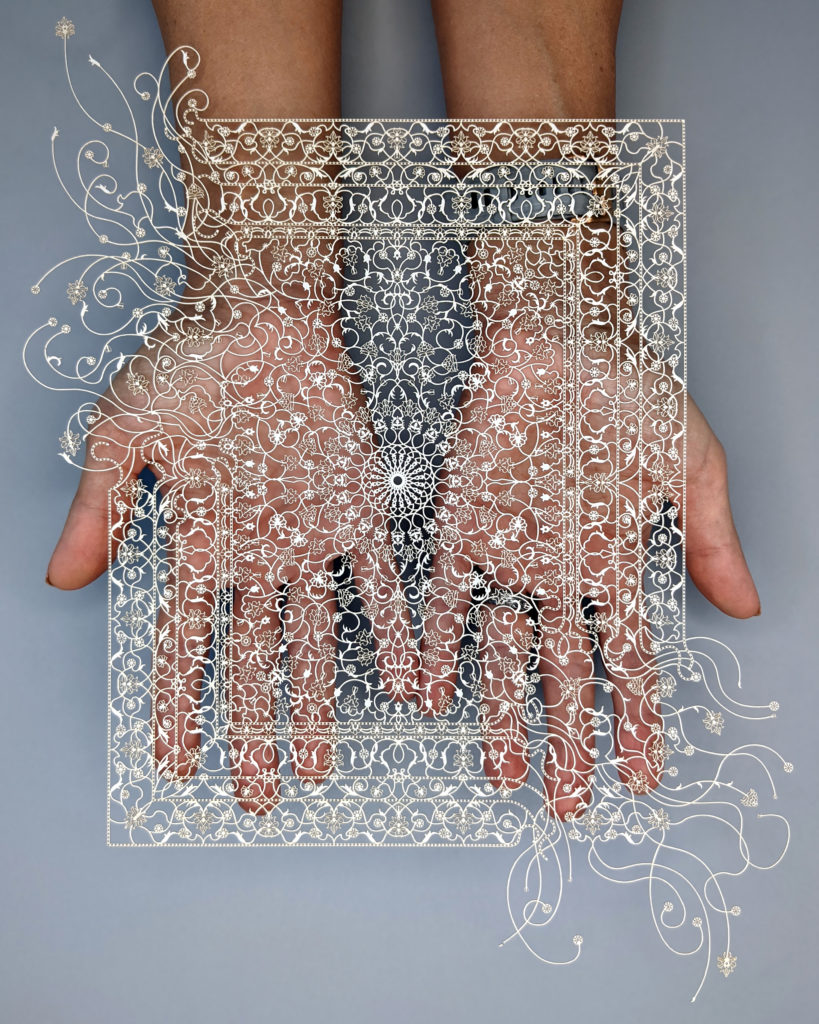

(J.I.): My work explores historical ornament through a contemporary lens, using algorithms and new technologies to create intricate works that intersect art, design and engineering. I have long been interested in design, graphics and collage and have always worked with computers. Earlier on in my practice, I worked with the idea of layering and meshing parts together, but the layers remained in the digital realm. The end result was often a print, which flattened all of the depth I’d been playing with. When I began working with laser machines and 3D printers in recent years, it allowed me to take this depth that I had been developing digitally to a very tactile and tangible place. The work continues to become more complex, with more layers, often moving into three-dimensional sculptural forms. Designing and producing the pieces now requires a more technical, frequently mathematical, approach.

(S.M.): What type of materials do you work with and why are you so drawn to them?

(J.I.): We work mostly with very thin sheet materials, such as paper or wood. Paper in particular can be cut with very small details, often fractions of millimetres. Much research is done into how to push boundaries and I love using materials in new or unusual ways: for example, taking veneer wood intended to be applied flat on solid wall panels and cutting it as fine as lace to curve it into a flowing sculptural form.

(S.M.): Your intricate designs can take up to 6 months to complete. Can you talk to us about the process from start to finish?

(J.I.): I spend a lot of time translating initial ideas, often very rough sketches, into a plan for a physical piece that can be built. We will generally need to develop new software, carry out material testing, and have dozens of prototypes made before it begins to move in a direction we are satisfied with. After the testing phase we move into the final design and build which can take months because although we use machines, final assembly is always carried out by hand using tools that range from simple pins to complex 3d printed moulds.

(S.M.): What is it about these Islamic patterns and centuries old Arabesque designs that fascinates you and inspires your work?

(J.I.): I spend a lot of time researching the origins of different ornamental motifs or patterns and how they have moved across cultures and continents over time through trade or exchange of ideas. I frequently combine ornaments, patterns or designs of differing origins within a single piece. I’m fascinated by the creation of visual complexity through repetition of motifs, elaborate geometric construction, or accumulation of ornamental detail. I’m drawn to the contrast between visual intricacy and underlying construction principles in pattern language; how complexity can emerge from simple rules, or, conversely, how complex constructions can result in works that appear simple or more minimal.

(S.M.): How do you incorporate technology into your work? What is the creative process like when working with a computer scientist?

(J.I.): Stéphane began collaborating with me around 2018. I don’t think he ever imagined that art and design would be a field where his computer science experience would be pushed to its limits. We have a very symbiotic working relationship with different ways of looking at projects, which together produce interesting and often unexpected results. I am always playing with how far I can push boundaries and ideas creatively, while Stéphane focuses on engineering quality. As a result, there is an ongoing increase in both the complexity of the pieces and the technology we are working with – which is quite exciting.

As we evolve in a space at the intersection of art, design and engineering, we often run up against the limits of what commercial tools are intended to achieve. Having a software engineer in the studio allows us to develop solutions to extend or bridge gaps between existing applications. This input is also really interesting from a creative point of view, as some algorithmic concepts and techniques can bring a lot to the practice. For example, we’ve worked with computational tree structure and graph theory algorithms, parametric design and developable surfaces with fascinating results.

(S.M.): How does the precision of technology and organic nature of human hands come together so beautifully in your designs?

(J.I.): Even though we use machines extensively during the production process, the pieces always start from hand-drawn elements and the end result is always assembled by hand, which can take hundreds of hours and as much skill as the rest of the process. I want the work to have that element of being crafted – that someone’s hand was there. There is something quite beautiful in that.

(S.M.): What are some of the challenges you face while designing these pieces?

(J.I.): Often we’ll start a new piece not knowing if it’s even possible to make. The engineering and craftsmanship required to build some of the works we create is frequently at the very edge of what’s possible for both us and the machines, so we have to fail repeatedly until we get it right.

(S.M.): You are also the winner of the prestigious Van Cleef & Arpels Middle East Emergent Designer Prize. How has the prize impacted your career and what does an accolade like that mean to you?

(J.I.): I was thoroughly surprised (and delighted) when I won. It cemented this notion I’d had that I could cross multiple disciplines (art, design, craft, engineering) in my work and be recognized for it. Tashkeel and VC&A were incredibly supportive and that in many ways helped me move the practice in directions I would never have considered before.

(S.M.): What are your personal views about being a creative in the capital, Abu Dhabi, and what has your experience been like over the years?

(J.I.): It’s a great place to live and work. I have always been able to access everything I need easily (machines, materials, space etc) which I value greatly. It’s also vibrantly multi-cultural which I feel has influenced my work in many ways.

(S.M.): What are you currently working on?

(J.I.): A mix of pieces for exhibitions, commissions, and art fairs. The most exciting however is a new sculptural work in its initial stages. I don’t know how or if we are even able to build it yet but we’ll get there eventually.

(S.M.): Is there any advice you would like to give to upcoming artists who are inspired by you and want to incorporate technology within their work?

(J.I.): Try everything that interests you, understand that you’ll need to spend a lot of time learning new skills that at first appear completely unrelated to art or design. Remember that technology is mostly about tools, your ideas, and your voice as an artist are ultimately what matter most.