Words: Zainab Mirza

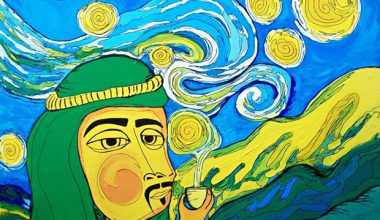

Images: Omar Sartawi

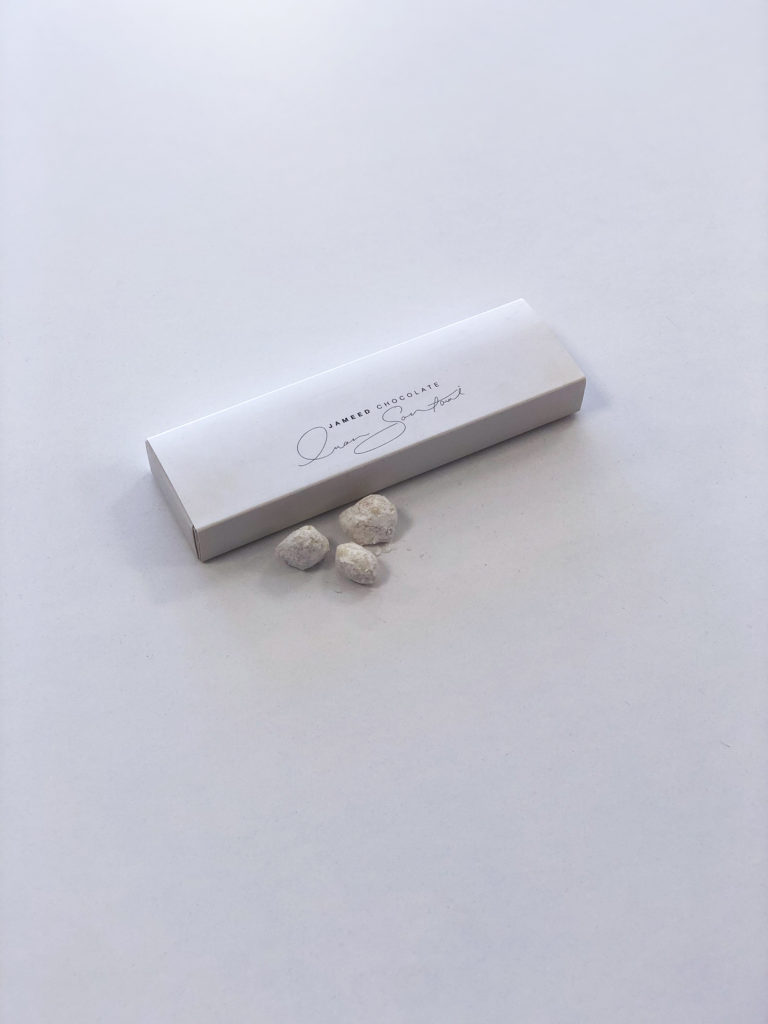

Jordanian cook and food artist Omar Sartawi made waves in the culinary world in 2017 with his creation of Jameed Chocolate—a fusion of white chocolate truffle and hard, dried yogurt made from fermented goat’s milk called jameed, which is used in mansaf, a Jordanian national dish.

In 2019, he used the same ingredient to create Jameed concrete to build a replica of Ayn Ghazal, a set of the earliest large-scale statues of human form, unearthed at the titular site in Jordan in the eighties. The edible replica was created for Amman Design Week 2019.

In late 2019, he developed a sustainable leather out of aubergine skins, and collaborated with designers Salma Dajani and Princess Nejla Asem to design breathable face masks in 2020.

Most recently, he embraced the constraints brought on by the pandemic with daily artistic impressions of the news that he would post on his Instagram account, along with the intended meaning behind the artworks.

I met Omar over a Zoom call to learn more about his transition from construction to culinary arts, the elements behind his creative drive, the influences on his approach to cooking, design, and art projects, and the reason why he prefers to be called a cook, not a chef.

Zainab Mirza (ZM): Let’s open with your entry into the culinary world. How did you go from managing construction projects to opening your own restaurant in 2012? How and when did your journey into exploring food first begin?

Omar Sartawi (OS): I've always enjoyed cooking. It was something my mom always joked with me about, that I should have studied culinary but I always thought it was too late for that. I was in construction in Dubai, doing some of the biggest projects there and managing some of those on the field. This taught me problem solving, which is good because when I came back to Jordan, I opened a design company.

We started developing restaurants, concepts, and designs, which helped me understand food. We started doing big events on the side apart from my design work, and started getting closer to F&B. From there, I had an opportunity to develop an Italian Asian concept called Food Box with a partner. I just kept learning. I started getting the best chefs I could afford, or the best chefs to my knowledge, and just cook with them and learn from them. I would just keep working with better and more established people. I thought I needed to learn, to become educated. So I got some professional training, I got a private tutor who teaches culinary arts. I did not want to go through two years of school. We trained everyday for 10 hours over three months. I read every cookbook I could get my hands on. From there I built my own kitchen and I started just working and developing further.

ZM: Was there a defining moment when you decided you were going to become a chef?

OS: When I used to cook before I got trained I used to make a huge mess. If I went into the kitchen to make pasta, you'd find tomato sauce on the ceiling, sauce under the fridge. I remember once before opening Food Box, after I got trained, just going into the kitchen and preparing six different pasta dishes in a very small place in a precise manner in just half an hour, and having a clean space. That was one of the moments I knew I liked this.

I’ve always liked people calling me a cook, not a chef, because I think being a cook is something out of a passion whereas being a chef is a job. A chef feeds people. I do the opposite. I want to make people hungry. I don't want to feed them. I want to make people question things. You go to a chef to be fulfilled. I'm the opposite. I want to engage you. I want to make you upset. I want to make you angry. Sometimes I want to make you feel something through food or art.

Another nice moment was with my grandma. I used to do normal French food, and then I started suddenly shifting towards more of what I like to do. The first experimental dish I did was based on a day I remember I had with my grandmother. We were having plain yogurt with some bread, and I was eating just the top of the yogurt because it has this thin layer. It was one of the most beautiful food memories I had. So I tried to recreate that by creating a dish, which is white on white with a toasted brioche and a sorbet of olive oil, and the skin charred. It had all these different textures. That was not the dish I ate with my grandmother, but the memory of it. I fed it to my aunt, to my mum. I just remember seeing her face and she had this smile, like she was a kid. It took her somewhere.

And this is the direction I discovered, one that’s feeding you something more than the physical. Like I said, I want to make you hungry. I don't want to feed you. If you want to eat, you go somewhere else. I don't mind feeding you something that doesn't taste good because it's part of storytelling. Chefs are obsessed with just making you eat food, which is delicious. I do in that sense, if it tells part of the story, but I don't mind feeding you something horrible either.

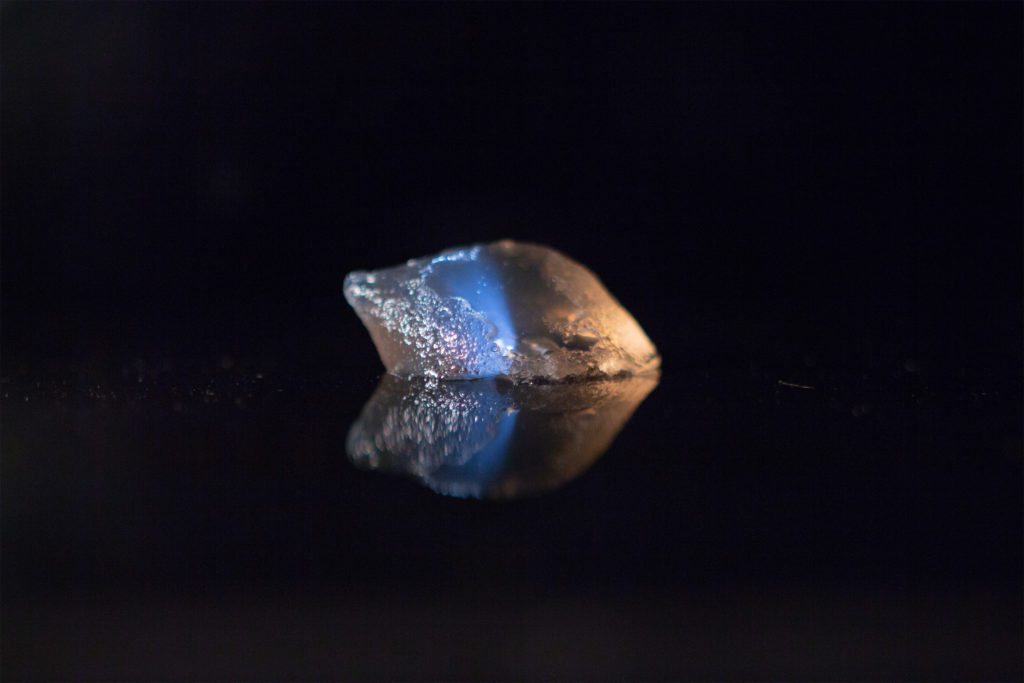

For example, jameed is the most international dish we have, and it's a harsh dish. It's from the desert, and it’s such a beautiful ingredient. It looks like a rock. Whenever I use it in anything, I like to show its harshness. And once you eat it, it's overpowering. I don't want to tame it down. I want to translate this expression. Food can express culture more than words can, with one bite. It's beyond the language barrier. So I try to do that, like when I introduced jameed. I'm never apologetic. I never shy away from showing strong flavors. So in that sense, I go more towards design and words to more expressing an idea conceptually than actually just wanting you to like my food.

ZM: How did you come to embrace food art and design?

OS: I did not start with wanting to become an artist. When I was learning food science and cooking, I was able to express myself better. But I also read about history, about philosophy, and the outcome becomes different. So if I've been reading on a specific subject, I find that my cooking would change with that. My approach to things would change. At one point I just started expressing what's happening around me through food. All my friends started calling me an artist and I would correct them saying no, I'm a cook. But the shift came gradually, and I started going towards that. For example, the Ayn Ghazal replica. I was approached by the director of Amman Design Week to exhibit (in 2019). We developed a material and I introduced jameed to it because I thought it's a Jordanian ingredient. Then we thought let's do Ayn Ghazal and shed some light on it. It's a beautiful experience for the world and not a lot of people know about it. So we developed a replica, displayed it, with the material next to it so people could actually eat it. That was something that got so much attention, and I think it was important work.

From there I did more experimenting and expressing. I did aubergine leather. It's a leather made out of aubergine skins that are treated in a specific way; they become leather and don't rot. They become durable. We did the mask with them and we're working with many amazing architectural companies to develop products with them. So I'm using the cooking as a base to express myself.

When Corona (COVID-19) came about, we had a lockdown in Jordan and couldn't get materials. Scarcity sometimes is the biggest teacher. I started appreciating little things, like a coffee stain. I did this series to express what was happening to us through Corona (COVID-19) on a daily basis, with photo manipulation. I would take photos with my phone and just have like a tomato and a cube and have them integrated together. Most people would not understand what they're looking at, but once I explain it, you can never unsee it again. So that was challenging from the point of not having materials and being able to think creatively, to find a good solution for such things.

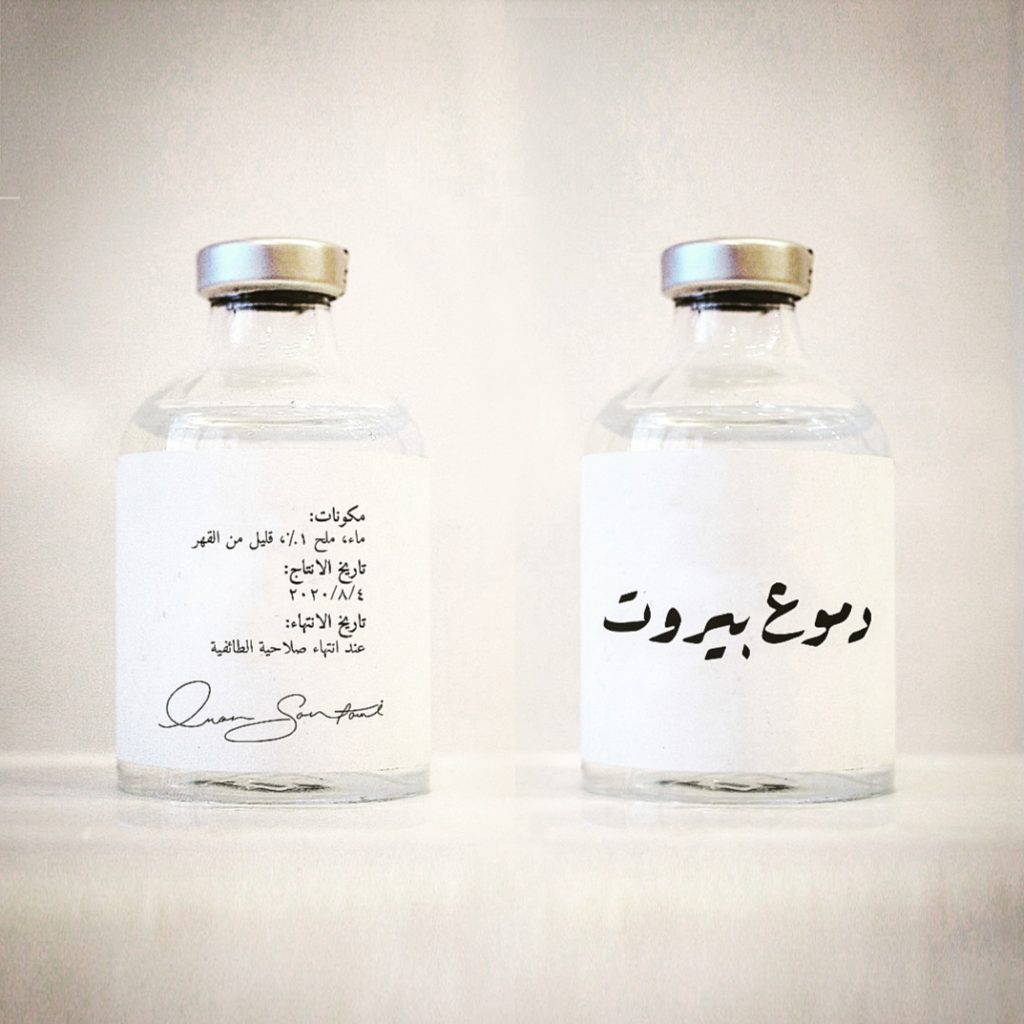

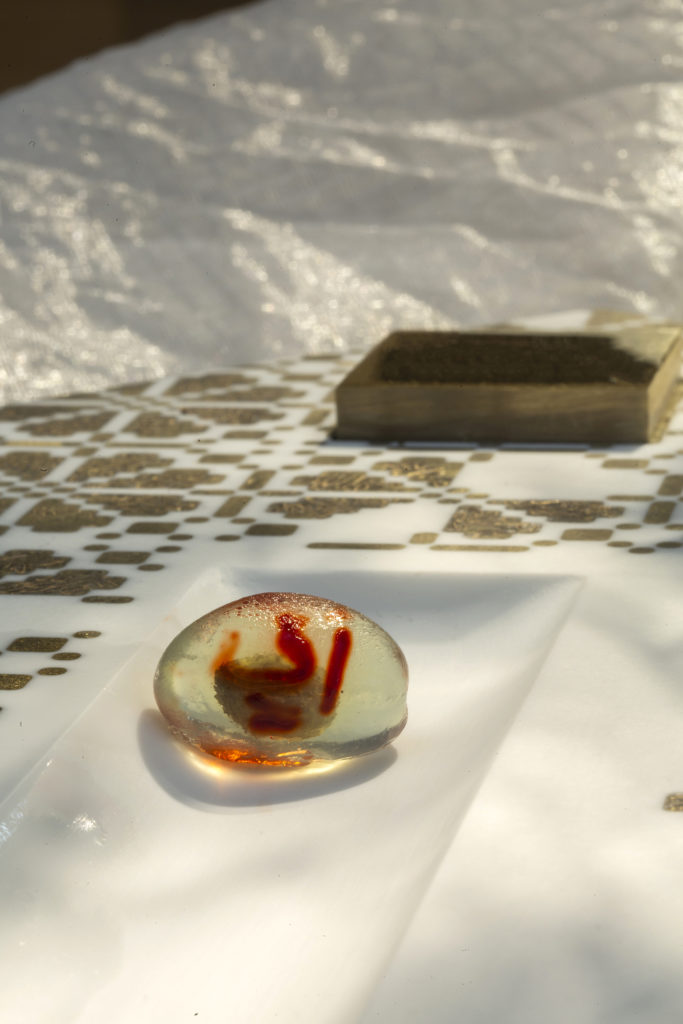

So I think that was leaning me more towards art. Then I did something for Beirut. I wrote the name of Beirut on a heart with a laser, because in Arabic, there is a saying that says ‘your name is written on my heart’. So I did, but literally put it on a heart. Then I thought that I’d season the heart with a tear broth. I tasted my tears and tried to adjust the saltiness of the broth, and seasoned the heart with the tears, which was an artistic expression. Afterwards, I did four limited edition bottles in Arabic, English, French, and Phoenecian, and we sold them for charity and the money went to Beirut.

So I'm more about expressing what's happening. I still cook, but I'd like everything I do to have a strong concept, to have a message.

ZM: Do you follow a similar approach when you're creating something, whether it's food or art, or is your approach different? Is your process different?

OS: Chaos. Chaos is a very powerful tool. I keep changing with the scenario. With the aubergine leather, I was just trying to create a leather replica. After six months, I discovered that I’d made a new material. But in the beginning, I was trying to force something. With time I thought, why not try to listen and see what the material can do? As the approach in those six months changed, the material changed.

If you work on things, from the bottom of our heart purely not only will the project change, the project ends up changing us. There isn’t one approach or one method because I keep changing. I keep developing. The projects I'm working on are always beyond my means. I'm never comfortable. I'm not repeating myself. So with each one, I'm pushing myself further. In doing that, you are at risk of failure every single time, but then you are equipped with tools that can take you there, that can hopefully get you a good outcome.If you are progressing with work, you never approach the same thing in the same mindset and in the same experience. So there is no one unique method in that sense.

ZM: What feeds your inspiration, your drive to create?

OS: Events around me, personal experiences like relationships, friendships, connections, current events, anything which is affecting me. I'm very interested in history, so there is always an element of it in what I do or a reference to it. Whatever is affecting me at that time will be part of the work I'm producing, whatever it is.

If I'm cooking, for example, for 10 people and I'm making them burgers, as Omar, the status where I am at would affect the burger. If I'm developing a restaurant concept, this is a different thing. I switch off the person I am and I just work on that thing from experience, from knowledge, from these things. But usually if I work on things personally, it is the personal things affecting them.

ZM: As an artist, chef, and restaurateur, what are the most significant challenges you’ve faced in your journey and how did you overcome them?

OS: With restaurants, the problems that I face most is the work culture that we have. It's difficult sometimes to get people wanting to learn, really learn, and have them understand that learning is a long process, and that afterwards building experience is an even longer process. Most people confuse learning with mastering. For example, you can learn how to make pizza in a month, and people assume that they have mastered it.

This is the biggest struggle, for restaurant developments and concepts, training people and making sure they deliver with consistency and not become arrogant after learning a little.

With art, each case would have its own struggles, but I would overcome them. I think the biggest problem with art is that it is portrayed as something light and for fun. It’s portrayed as though it’s for extremely rich people who don't know what to do with money or for entertainment. This is dangerous because art is very important. Art can be for fun, and I'm not saying it isn’t, but it moves you. It’s one of the things that affects you in life as a human. It is very influential. Trying to make art as something for entertainment makes it be taken less seriously, which is very dangerous because you lose one element of influence on people. People become more immune to it, and think less of it, when art is probably the most influential thing in the world, in the history of the world.

Wadi Rum

Kubeh

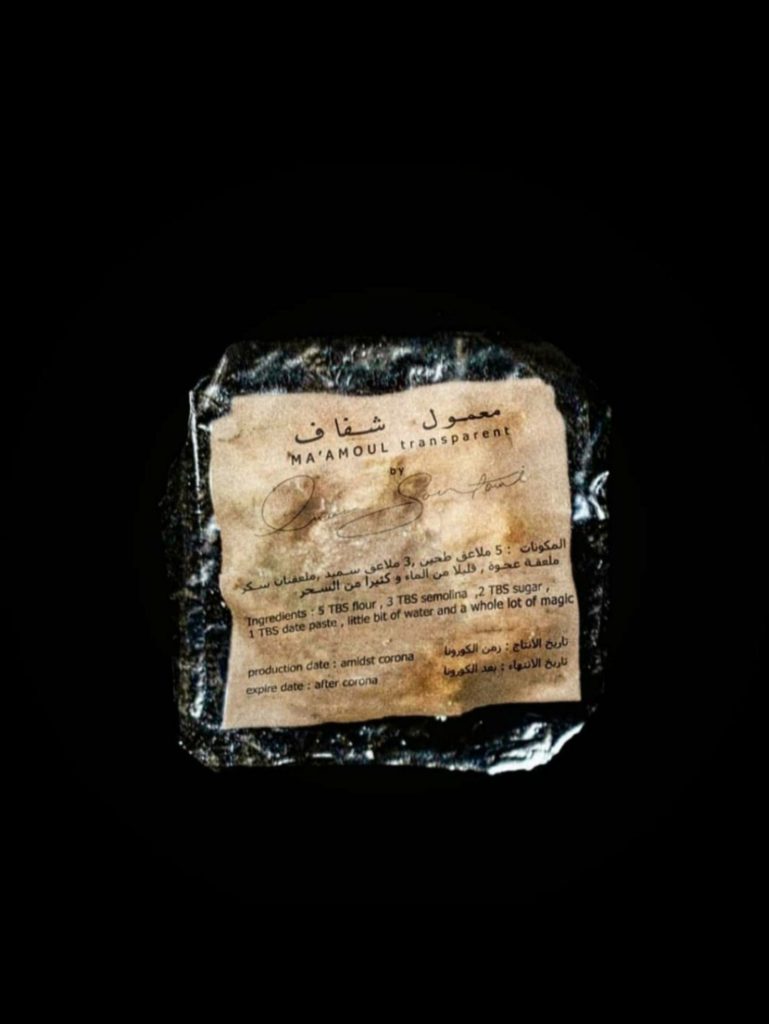

Ma'amoul

Desert meets Sea

ZM: What advice would you give to aspiring chefs or just inspiring cooks or aspiring artists?

OS: First, you need to read, you need to learn. There is the illusion of knowledge, and the more knowledge you have, the more of that illusion goes away. You have to keep reading about cultures and to understand the difference. You have to keep educating yourself. It never stops.

Being honest to the work, this is the second thing I’d say.

Number three is figure out what you like to do and do it with all your heart. Don't be afraid of failure. Don't be afraid of mistakes. This is part of the learning curve. Be pure and true to the thing and be brave to take things to a different level.

I always have to follow what's happening in the world where the trends are. The future is being created now; you can see people on Instagram creating the future. So you need to watch that and understand where the world is going and be relevant to that.

www.instagram.com/omar_sartawi