Words: Khaled Al-Qahtani

Images: Hamida Issa Alkawari

Inspired by her mother's habit of carrying a video camera with her everywhere she goes, Hamida Issa grew up to become a filmmaker with an ardent passion for films that document and narrate the stories of the places she called home in Doha (Qatar), London (UK), and beyond. She was among the first women filmmakers who contributed to the growing film scene in Qatar and the rest of the Arab Gulf. On a warm Friday evening in early March 2021, Hamida, from her home in Doha, joined Khaled Alqahtani in Tabuk on a Zoom call. In their conversation, Hamida traced back how her interest in film developed, her contributions to Qatar's first film festival, and her current projects.

Khaled Al-Qahtani (KQ): When and how did your journey with filmmaking begin?

Hamida Issa (HI): My journey with filmmaking began much earlier than one would have thought. It began in childhood. And I only realized that later on in life once I became a filmmaker. Looking back, I realized it began with my mother (may she rest in peace). She used to film everything on a video camera. I remember I started taking the camera from her once I developed the urge to document things myself. She passed away when I was 13.

I started making films in high school. In [my] English class, they would assign us to write a script. I'd be the only person who would film something and edit it and then screen it in class. So it was something that was almost second nature to me. I didn't realize until much later on in life that I wanted to become a filmmaker. The realization happened when I was 21 years old.

I went to UCL in London [to study] politics, and I thought I wanted to change the world. It wasn’t until my senior year when I was graduating that I got an email about ethnographic documentary filmmaking, and that there was a two week course being offered at UCL. It was unrelated to my degree, but, I don't know why, I just took up the opportunity automatically. I did the course and made the film. They taught me how to use the camera and how to edit properly. And I made a film about smiles on the streets of London. It was something very simple. But that made me realize that I do want to explore filmmaking.

Later, I got an email notifying me about the first film festival in Qatar, the Doha Tribeca Film Festival, in 2009. So I dropped my life in London and headed back to Qatar to work for this film festival, and to be part of this new wave of filmmakers and film movement happening in my country—to help grow a tree from the ground up. And so that was where my professional journey in film began.

We set up the Doha Film Institute (DFI) in 2010, and I was part of that team in the education department where we produced workshops for those interested in the community. After making a couple of my first films, I decided to go back to my studies and do a master's degree in global and transcultural cinemas at SOAS (London), specialized in Arab and Iranian cinema. So I went back to school to actually study films and develop the skill to watch them from multiple perspectives—from anthropological, psychological, and post-colonial perspectives, and even through the lens of national identity. So I got to study film in a very different way as almost as a text, and I feel like that really enriched my journey as a filmmaker.

KQ: Your films are inspired by the traditions, heritage, and past of Qatar. How did these elements ignite your passion for filmmaking and storytelling? How are they incorporated into your work?

HI: I believe I should start the answer by giving you more context about myself, what comprises my identity, where I'm from, and where I grew up before I go into why tradition and history really speaks to my cinematic language. I'm half-Qatari, half-Saudi. I left Qatar when I was seven years old, and I grew up between France and London most of my life until I was 21. When I heard about the film festival, I wanted to be part of this new wave so much that I chose to move back [to Qatar]. Growing up abroad my entire life has solidified and strengthened my connection with my past.

Living abroad, I used to always phone my grandmother, Mama Hamida. Because I grew up so far away, I've always appreciated the precious time I had with elders and hearing their stories. Whenever I would come and visit, I had a strong connection with this intangible cultural heritage that I feel needs to be recorded to preserve our oral histories and traditions. We need to focus on documenting and making sure our culture is everlasting for the generations to come because with this [older] generation, they're taking with them a lot of stories and a lot of things about our past that we might not necessarily know of [in the future], if we don't document them. So for me, it's about having this really strong connection with my past and trying to translate that in my films. It's a form of rediscovering my identity. It's a form of documenting and exploring my identity, and preserving it for future generations. And I feel like I've only just begun.

I used to call it narrative archaeology — you're searching for pieces of yourself through your community’s stories of shared traditions and history.

KQ: You’re one of the first women filmmakers in Qatar and the Gulf. This comes with the burden of having to represent your entire country. Have you sensed that with your career so far? If so, did it affect your work?

HI: It's not a burden. It's actually very empowering. I think there's a sense of responsibility to express elements of our national identity, of our culture in a beautiful way. I don't think it's a burden because I think it's a beautiful time to be creative and to be active. When can you ever be the only one in something? It's so rare to be alive and be part of a movement from the very beginning. It’s the most exciting thing to witness—planting the seeds for the film industry in Qatar and being a part of the new wave. And, yes, I was one of the first, but it’s exciting to see that there are so many talented and noteworthy women and men who are active in the film industry now.

I see all of these filmmakers coming up, and realize I've witnessed the birth of this industry. So it's not just me; we've all empowered and supported each other to this point. It's a small community. But I think there's a sense of responsibility to show the beauty of our traditions, the beauty of our religion, the beauty of who we are as people, and to show the beauty of the often overlooked women’s perspective of our shared heritage, which is not easily accessible.

KQ: When Arab filmmakers or any voice that is rarely represented in a certain industry is spotlighted, their work is always highlighted and produced in a way that appeals to Western audiences. It seems like it’s never made for the local communities that these films and stories are inspired by. Have you observed that? What do you think of it?

HI: I think it's very important to be aware of ‘orientalism’ and self-orientalizing. This inferiority complex that we always have to appeal to the West and prove to them that we are [worthy]. I think it's important for us to actually make films that speak to our people and ourselves. And that way, it becomes universal—the West is going to be interested in our stories because they speak a truth that hasn't been spoken anywhere else before. And it's done in a very authentic and genuine voice. I think it's about staying true to who you are, and making films from a place of sincerity.

KQ: You’ve witnessed the growth of cinema and filmmaking since your first short film debut, 15 Heartbeats, in 2011. What have you observed about this rapidly growing scene and industry? How do you imagine it becoming in the future?

Very early on in my career, I saw the amazing Palestinian filmmaker, Elia Suleiman, whose voice and vision for Arabs in cinema I truly respect. I went up to him, and I said, “I want to be like you.” It was before I made my first short film. He said to me, “How old are you?” And I said, “I'm 21.” And he responded, “You're not going to make real cinema until you're in your 30s.” And I was like, “What?”

I didn't understand that. But now that I'm in my 30s, I really understood what he meant. He meant that throughout your 20s, you're still figuring out who you are. And if you don't know who you are, how are you going to have a solid cinematic language and express yourself? I feel that any film that you make is an extension of your soul. It's your soul singing. It's a very spiritual, artistic, creative process. I feel like growing up these past 10 years, I've seen my cinematic language evolve. I started off with making 15 Heartbeats (2011), which is the first short film that I ever made that was screened in a cinema. It was screened in the Doha Tribeca Film Festival in 2011. No budget, but I still managed to make a film that moved people to tears because it came from a place of truth.

Since then, I feel like the seeds that were planted then have begun to flourish in different ways through the different mediums I've experimented with throughout my career. I took that advice on board in the sense that I tried to experiment with different kinds of filmmaking — I've made short documentaries, a music video, and an immersive video art installation. For the past five years of my life, I've been working on my first feature film and it's a feature documentary, so that has been taking up a huge part of my life, the part where you're really becoming who you are.

KQ: Your experience ranges from short films to music videos to an upcoming documentary. What projects are you currently working on? And what are your hopes for the future of this industry?

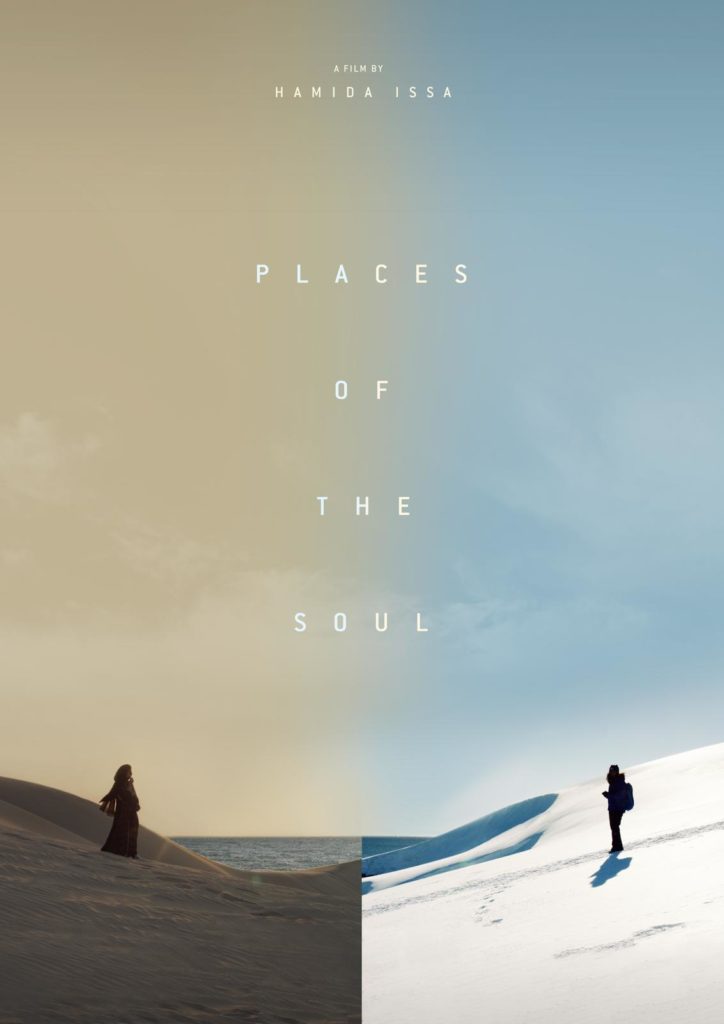

HI: I'm working on my first feature film, Places of the Soul, which will be released by the end of 2021. It's a documentary shot between Antarctica and Qatar. I'm the first Qatari woman in history to go to Antarctica, so this journey is a spiritual one and an exploration into matters of tradition, the environment, and the greater question of loss. It’s a personal and spiritual discovery, and a journey home away from home—a journey inward.

I'm excited for it to finally come out because it will be like my international debut. I've also been developing quite a few things. I've been working with a fellow filmmaker developing a script for a feature film. So I'm going to tap back into narrative fiction, a fantasy type of film. I'm also developing a couple of documentaries, which aren't personal but more informative. And I'm also launching three films through my own arthouse production company, Feryal Films (named after my late mother, may she rest in peace), composed of a collective of artists, musicians, and filmmakers from the region and the diaspora.

I think it's so important for us to have grassroots initiatives. And that's why I'm starting Feryal Films. Yes, we were so lucky that it was a top down decision from the Doha Film Institute. I wouldn't be a filmmaker today if it wasn't for this experience. But now there's this institution [DFI] that supports us, gives us a platform, grants, and educational opportunities and exposure for our films and practically holds our hand throughout the entire process. But then, we (the grassroots initiatives) need to also build from the bottom up, so we can meet (these benefactors) behind the infrastructure halfway. And that's how we work together. That's how our full functioning organic, holistic industry should work.

linkedin.com/in/hamida-issa-33470a45