Intricate Gergean boxes, a Le Notre Easter cake box, VIVA exhibition booths, Sultan Center, calendars, offices, and houses. It would appear that none of the above mentioned words have anything in common, but they most certainly do. In this case, it’s PAD10.

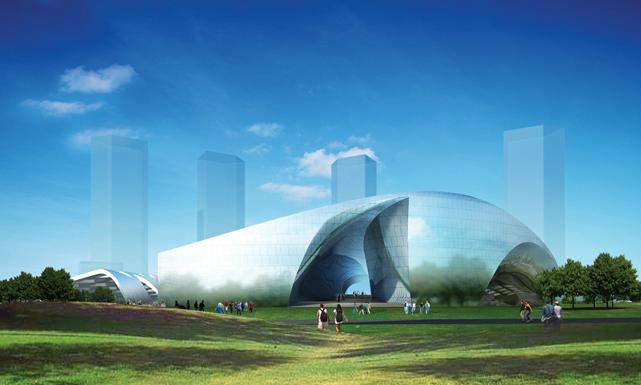

PAD10 is a publishing, architecture, and design firm that has been located in the heart of Kuwait City (with a breathtaking view I must add) for about two years. Their creative outlook on modern design has not only allowed them to apply their multi-skills in constructing local and regional buildings, but also to focus on designing advertisements, press designs , furniture, and branding. Their exquisite pieces (booths, furniture, boxes, calendars) are designed around waste matter recycled from press factories in Kuwait. What’s not to love?

Describing the 40 year old architect and founder as ‘impressive’ would be an understatement. His international experience and award-winning practice, along with his teachings of architecture and design, have landed him on our page.

Meet Mr. Naji Moujaes.

First off, tell us about yourself.

I received my Bachelors degree in Architecture from the American University of Beirut in 1996 and my Masters degree in Architecture from the Southern California Institute for Architecture in 1999. I lived and worked in New York for 10 years and came back to Kuwait to settle down with my family. I was very interested in architecture and graphic design, and I also worked with music installations with Nadim Karam, my professor at AUB at the time; I spent one month in Prague for an art installation on Manes Bridge. I got involved in different design aspects, including sound design. That interest was always there, the visual and spatial communication when it comes to design. This is where the thread goes through PAD10; communication in collaborating with other fields to try to address any challenges we face in architecture.

What does PAD10 mean and how did it establish itself?

It stands for Publishing, Architecture, and Design. It is an interdisciplinary platform where none of the creative disciplines per se is dealt with as hermetic, but rather as complementary to one another. We work on many projects jointly, where graphic designers end up branding architectural projects architects work on, or architects designing exhibitions with guidelines set by the graphic designers. To start, the idea was to create a platform bringing together the graphic designers from FourFilms, the exhibition designers from 4F.E.S.T, and the architects from L.E.FT, which I co-founded in New York in 2001. It ended up being a hassle, so I merged them all under one roof as PAD10.

So Four Films and 4F.E.S.T are sister companies of PAD10, what does each represent and what do they produce?

They are related parties. FourFilms is a leading printing press in Kuwait and 4F.E.S.T (FourFilms Environments, Signage and Trade Shows) builds interiors and exhibition booths among other things. Coming to Kuwait while designing a printing press, I used to walk around the facility and saw all the waste put aside from paper leftovers. In the absence of recycling facilities and when the paper waste started accumulating, I saw the opportunity to make our stationery and my sketchbooks. From there emanated Press Designs, the eco-friendly brand of PAD10.

PAD10 reclaims any waste from FourFilms Printing Group or 4F.E.S.T workshop and designs around that. The design objects are all limited edition and the materials utilized in crafting the collection include paper, wood, metal and acrylic. Products have included puzzles, books for kids, stationery, and jewelry boxes. All the furniture at our office is produced by Press Designs from reused MDF material and plexi-glass.

Jointly, with 4FEST, we won twice the VIVA exhibition booths at Infoconnect. PAD10 has a total of 25 employees only. We are a very small operation, but we also have help from 4F.E.S.T and FourFilms to create many turn-key solutions.

PAD 10’s work and research about architecture, art, and design is documented in the ‘the Kulture Files’, a quarterly pamphlet, which you can also find online.

Your first project was redeveloping the Pearl Marzouq building in Kuwait. Tell us more about this.

We were fortunate to examine the Pearl Marzouq building and that was before I came to Kuwait from New York. I was walking the usual walk with my father during sunset and I saw the Pearl Marzouq building and I was very impressed by its architectural posture, plus the richness of the façade, which reflected that it was not your typical residential building. I started visiting the complex and I kind of implied how the sections worked. In all cases, during that trip, I went and registered my name wanting to live there when I return from New York. This was two years before I came back for good and I knew I was making a move back. I met with the architect who worked on it and he talked about its history and showed me its plans. Unique to any other building, it’s docked on the sea, and being in Beirut and in Kuwait, I think the biggest urban failure is when you have the highway cutting the city from its sea. Plus, architecturally, the context with the planning was what attracted me to the building. I started a community website which highlighted the risk of this modern icon getting run-down. I think I got a listening ear from the owner himself and when they met me there was already a project in the making, but I thought the project didn’t go deep enough to address the building’s problems: t had less of an aesthetic problem and more of a programmatic one, add to it technical, safety hazards, and operational issues.

When I basically told the owner how it could be addressed, they were interested and this is how we pursued the project. When we started working on this project, the graphic design team started the branding and reexamining the website and brochure, branding it.

Your second project was the Kuwait Blind Association Sports Facility where you had to present it to the board members who are mostly blind. How did you address that?

Risking loss of the land, KBA association needed to create a sports facility as soon as possible PAD10 took on the project pro bono. It was very difficult because usually, the normal mode of client’s presentation is by drawing plans, sections, and making models. All the board committee were blind, so we had to devise a way to bypass this challenge and ended up using embossed metal plate with Braille to walk them through the project.

We hear so much about “modern” and “eco-friendly” architecture. Working in an advanced architectural firm, how would you define it?

At some point, architecture was classified in ‘styles’ and I think it should become more of a mind set or focused on process; we should be aware of specific techniques and technologies around us. PAD10 plays a very fine line dealing with contemporary issues yet avoiding being gimmicky; architecture sometimes runs the risk of getting contaminated with excess in technology. Architecture shouldn’t become a device, but instead should be something that you can cherish and reflect onto; if it’s a house, you should feel that you are home. Plus, there are more responsibilities towards architects when we talk about the Green Movement, as it may become an easy fallback; it’s becoming more and more of a selling punch line. I don’t think we should exhibit our lungs to celebrate breathing. How a building operates should be inherent to any architectural project without making it the central theme of the project; it should be done smartly, and with sensibility to the environment, yet move forward from the there to the social and cultural dimensions that architecture shall put into play.

Architecture should be the big topic, and everything else from within. If architecture reduced itself to be green, the greenest we can get is not to build the building! When you inhabit a place, it should improve all your interactions and give you a pleasant environment. Our own office barely uses artificial light because we’re already surrounded with glass and natural light.

How does PAD10 differ from other architectural firms in Kuwait?

In Kuwait, most architectural firms offer a service we don’t: engineering. They always have it to become a one-stop shop to international consultants and clients, which makes architecture suffer. We fully refuse this service because engineering is a discipline that needs its technical know ,how, that that we currently don’t have. Instead, we collaborate with engineering offices and have graphic designers. Bad graphic design doesn’t kill you, but bad engineering does and I’m not able to take responsibility over this one.

What’s your favorite building in Kuwait?

I am most fond of the Majlis Al-Ommah [the Parliament]. It was the first in the Gulf to celebrate democracy by its parliamentary building. It created a setback for the concrete canopy where the parliamentarians and citizens could interact, which was a very urban gesture. Plus, when you look at it, it’s always contemporary, even if it’s old because it managed to capture utmost technology of its time and present it in a very abstract timeless manner. The canopy’s shape, derived from the tent, is very relevant to this culture. Yet, it was captured with prefabricated concrete, giving lightness to solidity. Kuwait is much older than Dubai and it has a finer urban grain. But in many instances, it’s just being taken for granted. If I had to describe Kuwait’s architecture in one word it would be “moments of hope” and this is what I’m trying to cling to.

Speaking of Dubai, what do you think of the city’s transformation into busy highways with modern skyscrapers and manmade islands? Do you support artificial productions?

I always get this question, and yes, I mostly agree with what Dubai is doing. You need an urban densification with overlays of successes and failures to stratify a city with specific complexity. I’m not sure Dubai actually had a plan or structure to start. It developed projects of excellence, but buildings randomly just sprout. I think what Dubai is trying to do is avoid the demise of post-oil Arab cities. They’re jumping the gun and to do this, there are so many cultural and social phobias that they had to bypass. This is a good struggle to start with. Qatar is aiming to become like Dubai, but I hope they do not make the same mistakes by taking a step back.

What project of yours are you most fond of?

It’s too early to say, because we’re still in the becoming years, but if I had to choose, it would be the Pearl Marzouq Building.

Can you let us in on your current projects?

We are working on institutions, private residences, office spaces, and retail. Under construction also is a chalet in Bnaider, for which we are doing landscaping and interiors. We are also working on a project in Qatar and another in Khairan.

– Iqbal Al-Sanea

Images courtesy of PAD10