Words: Malak Al-Suwaihel

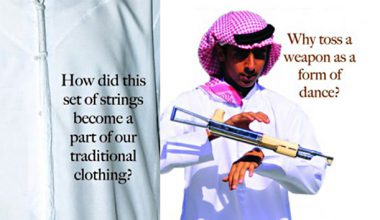

Images: Salam Zaied

Colette Dalal Tchantcho’s integration of names are hued by the multifarious cultures, and diverse histories and heritage that make up her arrangement. Colette occupies a space of liminality—an interstitial passage between her fixed identities of Kuwaiti and Cameroonian—where she has found her mode of expression through the art of performance. Colette, an actor and theater maker by profession and storyteller by passion, is an earnest art lover and fierce advocate of Arabs for Black lives and women’s rights beyond the veneer of hashtag culture.

Born and raised in Kuwait, then graduating from The Liverpool Institute of Performing Arts (LIPA), Colette has since moved on to star in TV series The Witcher, Netflix (2019-), Domina, Sky Atlantic / Epix / Now TV (2021), and Doctors, BBC (2018), as well as theatrical productions including Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, and was invited by the Shakespeare World Stage at the Globe Theatre to translate and perform five of Shakespeare’s sonnets in Kuwaiti Arabic.

True to the nature of her worldly name, the Khaleejesque team and I have been virtually following Colette around the globe since Fall 2020. Adamant to have her grace our next cover as the star personality—from her short stay in Kuwait over Summer 2020 to our failed photo-shoot of Colette on the set of Domina in Italy (due to heightening COVID safety measures)—we finally secured a time and date to remotely shoot Colette in London through the skilled lens of Salam Zaied. A portrait and fashion photographer with Middle Eastern and West Indian roots, Salam’s portraiture work is signified by her striking use of color and vibrancy with an aim to diversify the creative industry. From our delightful Zoom conversation, Colette’s skilled narrative voice expounded on topics ranging from education, dyslexia, and identity to the creative industry, acting, and community-building as an Afro-Arab in the Arab world.

The liminal space also occupies a threshold stage between waking and dreaming. Both consciously and subliminally aware of her multi-layered states of being, Colette is currently gearing up to release her self-reflexive, autobiographical solo-show, Dreamer. About the realities and experiences of a black woman in Arab society, Dreamer, Colette shares, is “depicting my upbringing in Kuwait. It’s my world. And I hope that it shares the Black-Kuwaiti specific story.”

Background: ‘What’s in a name?’

Malak Al-Suwaihel (MS): ‘What’s in a name,’ Colette Dalal Tchantcho? This phrase from a Shakespearean soliloquy is one that a LIPA trained actor is more qualified to deconstruct. But more than our shallow understanding of this Shakespearean phrase, it’s a query that questions the nature of a name as an arbitrary label. But not in your case where it takes on layers of meaning and multiple reference points. Care to elaborate?

Colette Dalal Tchantcho (CDT): Yes, Tchancho is my surname—my father’s surname—which is authentic to West Cameroon. So my father’s family are in the countryside of Bangangté. He left when he was 16 to Lebanon, then to Kuwait. He has since passed (may he rest in peace), but has been in Kuwait longer than he has been anywhere else. Although Cameroonian, and very well known for his work and his connection to the African community in Kuwait, he was very much connected to the larger Arab community as well. He maintained the Lebanese accent he acquired in Lebanon, which was quite entertaining for me and my family.

MS: Right, so that takes on multiple forms when one attempts to probe your past. Half-Kuwaiti on your mother’s side and half-Cameroonian on your father’s side (Cameroon, an ex-colony of France). Can you talk to us more about life in Cameroon? Did you ever pick up a Cameroonian language? How did your parents meet?

CDT: In Cameroon, being an ex-colony of France, one of the main languages is French. A lot of people there do speak English as well. My father spoke French, predominantly. But there also were the tribal languages of Bamileke, which was much harder to learn. My first memories of hearing it was when we went back to Cameroon and we met our family—there was a huge ceremony. As children, our memories tend to romanticize certain events. I was told for a long time that my father was chief of his tribe. But I think that was a term used to help us better grasp how high his position was. And to hold that position at such a young age, he wasn’t able to fully commit and be with his tribe. He lost his parents at 15 years old, and by the age of 16 had gone off to pursue body building—which is how most people know him, as Mr. Cameroon.

From there he went to Lebanon, where he noticed a growing interest in martial arts. Inspired by this growing trend, he went to China to partake in official training in Karate Shotokan and Judo Kendo and Sumo. After getting his black belt, he returned to Lebanon where he set up the Karate Federation there. He then moved to Kuwait to become a personal trainer and nutritionist, hired by the Al Ghanim family. Whilst he was founding the Karate Federation in Kuwait, with a few other founding members, my mom was sneaking out to go to sports clubs. She attended his Karate classes and the rest is history.

MS: Without flattening your experience or romanticizing how you may identify yourself, you seem to be treading the grounds of liminality quite seamlessly—an in-between space where you are continuously a ‘being on the border.’ Because language is a cultural repository, can you speak to us more about the significance of having and maintaining a native language, or ‘mother tongue,’ and ‘borrowed languages’ of expression to someone such as yourself that is ‘on the border’?

CDT: Language is such a tricky thing. It informs culture. And when someone is outside their culture of origin for many years, which a lot of people of numerous backgrounds are in Kuwait—they end up adopting a third culture, and that becomes home. Sitting between where they are and where they're from and the culture created in that place. I sit between my parents—my father who grew up speaking Bamileke, but because of his constant traveling spent most of his time speaking French. In Kuwait, he taught at Lycée Français de Koweït (LFK), an international French school. On my other side, is my mother whose mother tongue is Kuwaiti-Arabic. And my middle ground, like so many Kuwaitis, is English. My parents decided to send my siblings and I to an English School, the British School of Kuwait (BSK). My mom’s reasoning has changed here and there, but primarily they wanted us to have a language that would help us access the rest of the world.

When we talk about ‘mother tongue,’ often the assumption is that we live in one language. But often, this isn’t the reality in Kuwait, because from my experience there are many who live in this in-between space of Arabic, English, and even French! Even with kids who are “fully Kuwaiti,” because of their international education and/or because of their interactions with expats, domestic workers, etc., they default to English. Part of this conversation are kids who pick up Farsi or Tagalog or Indian languages that are often discarded [cast-off as inferior], which distances us from the Kuwaiti reality and the varied non-Arabic or English speaking communities within it.

MS: Yes, not to mention our Kuwaiti history attests to the same: a diversity of peoples and cultures travelled to and crossed what was historically a strategic trade port, as far back as the ancient Greek colonization of our islands and the bay of Kuwait. Kuwait is not a monolith, by any stretch of the imagination. For lack of a better word, Kuwait can only be identified as ‘cosmopolitan’—despite its tribal and political majority naysayers. There are nuances of difference amidst our ostensibly shared heritage, culture, patriotism, etc.

CDT: I wonder where that chain [of power] begins? I mean, [the obstacles] that [hinder] this ‘cosmopolitan’ reality and core of our culture. I grew up mostly in Kuwait. While my family [in Kuwait] is Sunni, we had a lot of Shia neighbors around us in Daiya [area within the Al Asimah governorate in Kuwait]. It is so complementary and a great way of creating bonds for someone [as sociable as] my mother. When visiting the co-op in Daiya, she sprinkles a bit of Farsi in her speech. Her father, my grandfather, spoke eight languages and bestowed that respect onto his children. And that’s fantastic! That’s the best thing about Kuwait. Or how we borrow mannerisms depending on who we’re talking to—we tend to mimic the person we’re speaking to—a beautiful gesture that shows our willingness to merge. We do know that Arabic is the core, but also at our core is showing respect by borrowing.

Schooling: Clearing Up Misconceptions and the Neurodiverse Experience

MS: I’d really like for you to elaborate on that—the spaces Afro-Arabs both occupy and are unjustly denied throughout Arab history, the present, the Arab body politic, etc. But to give the subject matter its due diligence, and seeing as we’re going chronologically, let's give it more time later.

I don’t mean to pry into what may be a sensitive subject, but I do believe it’s one worth posing here for its potential benefit, and it certainly will educate many. I’d like to ask you about your dyslexia, and how it affected your schooling, how it helped you turn to alternatives, and how those alternatives helped you pave the way for a career in the creative industry?

CDT: Wow, I’m so glad that you asked this question, because Kuwait and the Gulf region are so new at having this conversation about dyslexia. For my generation and older, there is a lot of shared trauma from people that felt that the education systems here threw them to the wayside. The amount of people who couldn’t keep up with the curriculums… For those who were privileged and had family businesses to fall back on, were promised a career and could just be propped up in a position. But there were those of us, like myself or those who didn’t come from prominent families or had family businesses, were having a hard time. There was such immense stress, with the added pressure of limited socially acceptable career choices in Kuwait for Kuwaitis beyond the bounds of being a doctor, pharmacist, engineer, architect, etc. How many doctors and engineers can we have?! Surely the workforce demand does not match the amount of people ushered into these positions.

I always asked, well what about us creatives? The options for us in Kuwait are limited as well—you either become an engineer or maybe even an architect if you want to do anything creative. But, ya mama [she says in exasperated jest], this can’t be it! It was really hard. But back in school, when I was at BSK where I was outperforming in athletics and art, it was like I acquired an exceptional status. They let me miss classes sometimes to practice singing for concerts where I represented the school in front of an audience of ambassadors and high ranking military.

I was thriving in elementary school because the learning process involves colors and songs, and I was just eating it up. I had a teacher, Ms. Hilary, who played guitar and sang to us and that engaged my imagination, which made the learning process much easier. Back then my teachers were telling my parents that I needed to skip a grade because I was really excelling […] and I skipped a grade. Once we started reading and comprehension exercises, my teachers started noticing that I was struggling. I just remember exploring reading in a creative way, and asked myself why the sound didn’t match the spelling. It took a teacher who was aware to recognize and explain my way of learning. Otherwise my school saw it as a way of being unruly and my grades, especially in spelling tests, suffered. I was shamed and publicly embarrassed for my dyslexia. I felt defeated. It was not a space for me to be explorative.

I got to a point where I began to find myself again in stories—from my early English literature classes. I had an English teacher who, when reading aloud, acted out all the characters through her pitch, expression, and voice. Just really performing. And while all the students were falling asleep, I’d be so taken by her [performance]. Later when I got home, I’d still be thinking about those characters and creating my own stories. When drama was introduced to the syllabus, I finally felt like there was a haven for me. We were having discussions about the behavior and psychology of people. No stone was unturned. It was an environment that I was already used to. My family, we used to sit together at the sala [living room] during family gatherings, and they were so good and so engaging in telling us about their week—telling stories. They also played classical instruments. That’s what reengaged me, that’s what made art so interesting and relative. It was my haven because everywhere else in the education system, I found it difficult, and it failed me.

Agency, Mobility, and the Pursuit of Dreams

MS: The education system was designed for those who can be categorized as ‘neurotypical,’ it’s notorious for letting down creatives such as yourself. The decision I’m sure was difficult, but in order to pursue certain life goals or dreams, especially in the arts, one must move to a more tolerant space or a space where opportunities are more ample…

CDT: What propelled me is.. I always resist to name this person, but I had a particular set of teachers and my parents who believed in me so much that I was able to dream up possibilities [for myself beyond Kuwait]. They all pushed me to apply to drama school, and it was beyond anything I could imagine, being from Kuwait. I went to a school in Liverpool [LIPA] that was established by Paul McCartney [of the Beatles]! And I was given an unconditional offer to go there, I couldn’t believe it. After graduating from there, I was signed and able to enter the creative industry of performing arts in the UK. I started going to auditions, and there was so much to learn! This isn’t your conventional work schedule—a 9-to-5—I didn’t have anyone around me who had gone through the same path. I had to continue to trust myself to keep going.

I remember having a conversation initially with Hayat Al Fahad [famed Kuwaiti actor] who was our neighbor at the time. I wanted to ask her so much, I wanted to be in her world. I wasn’t as integrated in the [Kuwaiti] society as she so expertly was and played on Kuwaiti Television. Kuwaiti Television at the moment is only accessible and shows one bit of Kuwait. The national station is not representative of the full scope of people in Kuwait. Kuwait has always been a transit hub—from its history we know that. But till now I don’t see an integration with the immigrant population and the local, Kuwaiti communities. For some reason there is a limit to how much, or how far, that integration can go.

The range of radio, TV, theater—I’m not seeing my story, my personality, reflected on screen. I was and am bold and loud—my mother used to say I speak in my Kuwaiti dialect like a boy. Well I had four brothers and male cousins, so I was such a tomboy. We have these differing and varying pockets of people, where are they in the media? Hayat [Al Fahad] is such a wonderful lady, but during our conversation, I began to collect this sense of difference [creating a boundary between us]. In her eyes, I could tell she knew we were completely different, and the opportunities that I have are not the opportunities that she has. I can take as much advice from her, but because of these [existing systemic barriers; the societal pecking order], I don’t see how I can enter the Kuwaiti entertainment industry on my own terms.

My mom’s solution was for me to become a TV presenter or host—but I’m not a presenter! Or to start off in roles that I didn’t see myself in like playing the role of a maid, like a Bahraini actress that presented as South Asian started her career as. No offense to anyone, but I maintained this resistance in me, I am not about to perform a maid on national television and accept that as my position! To be obedient enough [on the chance that I will eventually] be given bigger roles. I’ve put in the work, anyone who saw me working early on in Kuwait will vouch for me.

I remember watching Sulaiman Al Bassam [Kuwaiti playwright and theater director] and his team perform Shakespeare’s Richard the Third. That’s when I thought I needed to receive professional training [in acting]. And because I predominantly spoke in English, I went to the UK. So after all of that, you expect me to play the [disregarded and disrespected] role of a khadama [domestic worker]. I couldn’t exaggerate this narrative—this disrespect—in aligning an Afro-Arab with such a position. I couldn’t do it!

MS: I was waiting for you to say it first. The constant struggle against a vulgar prejudice, particularly in your space of identification, the copious layers of discrimination depending on where you are geographically: Arab, Black, woman, etc…

CDT: Yes! Recently I was watching Bye Bye London (1981) [a renowned Kuwaiti play starring beloved late Kuwaiti actor Abdulhussain Abdulredha] on Netflix, and everyone was harping on the nostalgia of the play. I saw a scene where Abdulhussain Abdulredha says something like, ‘hathy shway ghamja hag wahda Braitaniya’ [this woman is too dark for someone who’s British]. And from that comment, he goes straight to sexuallizing her and throwing lewd remarks. Everyone was laughing! Or a scene involving a black man who cannot be seen when the lights are dimmed, and the ghettoization of black cast members and background dancers, and it goes on. I was mortified by the idea of going on stage myself and being subjected to this kind of [ridicule]. Having to adhere to this treatment might have been easier for me—to have stayed in Kuwait and endured a few years of this—but I don’t know who I’m going to be when this kind of behavior erodes me and my self-esteem that much.

Enough is Enough: Afro Arab Consciousness and the Role of ‘Arabs for Black Lives.’

MS: And through your activism, you clearly haven’t entirely abandoned or lost hope for the future of Black Arabs navigating the social, political, professional scenes throughout the Arab world. The COVID-19 pandemic of the past year and a half (2020-2021) has truly shined a light on an array of protracted frustrations from gender and women’s empowerment to the disillusioned youth’s outcries against the current faltering economic systems.

But most ardently, we’ve seen with issues of racial discrimination a seismic shift after the explosive Black Lives Matter movement in the USA received rampant support online, globally. During the summer of 2020, after the resounding impact of the movement reached our shores, yours was a leading voice in the adapted and equally crucial campaign, Arabs for Black Lives. I’ll hand it over to you…

CDT: Forgive me if I get a bit emotional. So I was here, in London, as the video of the murder of George Floyd came up [online]. I saw African-Americans, Black-Americans, People of Color (POC) in America, and allies stand up in arms [against the violent injustices committed by police officers against Floyd that resulted in his death]. And I also watched people in the UK protest their hearts out. I watched the ally community educate themselves, advocate, call-out massive television distributors, and take on huge organizations and for those organizations to feel compelled to listen and respond to the voice of the people.

I then thought of every single time I’ve been in a sticky situation in Kuwait, and the people closest to me, those I went to school with and were raised with, chose not to stand up for or with me. I remembered so many events where people were ashamed to be in relationships with me, and that comes with merely being seen with me. [I’ve been in situations where] people would toss money at me and tell me to dance, in a way that was [demeaning] because I was an entertainer. I watched people have blatant prejudices against me. And I watched as people around me defended those people to me because they had more means.

This behavior I saw in my relationships, friendships, and even family. I watched the way they talked to and discriminated against each other. It’s like a Cinderella situation where one of my cousins, who happens to be darker skinned, and I know that I’m biased, but she is the most beautiful woman I have ever seen. But she was treated like crap in her household because she was darker skinned. And I’ve seen her self-esteem [falter]. Socially, we [Afro-Arabs] are seen as disposable people. So if you wanna have a naughty sexual experience, if you wanna pick a fight and guarantee that even we police ourselves, who’re you going to go to but to a family that can’t stand-up [against your privilege].

So many times I was told to simply walk away, and I never understood. But I put the events and experiences together. Oh, so we [Afro-Arabs] don’t have agency, we don’t have socioeconomic status, opportunity and places where people practice respecting us, and aren’t put in positions of power. We’re targeted most. And yet, when this conversation [of Black Lives Matter] reached our shores, ‘ee hathy Amerika [oh, that’s just in America], we have nothing to do with this. Ehna kana [here we are], in our society, you’re like my sister. You come to eat with me.’ And sure, yes, we eat at the same table, but how integrated are we when I can’t marry your son and your son is ashamed to bring me home or come to my family and ask for my hand [in marriage].

We’ve come this far, and we’re still being called ‘‘Abeed’ [a derogatory Arabic word used against Afro-Arabs and people of black descent]. Even through a compliment, you’d hear, ‘Oh she’s so beautiful!’ And the response would be, ‘minu? hel ‘abda’ [who? This derogatory term for black people].

MS: That word especially! The defamatory, racist nature of that word. Anywhere else in the world you’d be called-out for using it—cancelled into oblivion. But here [Arab Gulf], no tangible repercussions!

CDT: Exactly! I mean, it’s the equivalent of the English ‘N word.’ And people here say it with no shame, we don’t fear being disciplined, we don’t fear the repercussions of it, because there are next to none. In Kuwait, it’s so common to see someone throw that word around and [explain] that it’s a description for black people. No, it’s not. If you want to say ‘black,’ then say black. But ‘abeed is specific…

MS: Yes, it’s weaponized—verbal ammunition. If history has taught us anything, then we should be wise enough to recognize that said racial, classist, and gendered violence is present here in Kuwait. It’s dormant and insidiously lurking on all levels—from the political and bureaucratic to the social and interpersonal. Why does it have to reach physical violence on a mass scale for things to change (rhetorical question)?

CDT: Yes, and we are so psychologically defeated in so many ways that we know better or rather avoid that kind of confrontation, to create such a resistance that will bring an aggressive push back. With the small kinds of protests within the [black] community now [in Kuwait], look at what we’re being faced with! Can you imagine what an actual protest may bring? All you need to do is look at Instagram to see the amount of people that say the most horrible things [against black people in the Gulf]. I’ve had young black Kuwaiti women send me screenshots of the most atrocious comments. I had someone accuse me online of being fame-hungry [because I’m speaking out]. I had somebody else deflect his remarks after he commented about remembering me from school as the girl with cornrows in her hair. No, I didn’t. I had braids. And he thought he remembered my brother as some other black child [implying that all black people look the same].

He expected me to behave in a way that was grateful and kind regardless [of his microaggressions]. He asserted that information on me and got upset when I wasn’t kind and happy to receive it? No. No more am I [complying with such behaviour]—randomly picking an African country on the map for me, discarding that I’m half-Kuwaiti, picking a random black person and asking if they’re related to me, or picking some random Afrocentric hairstyle saying that I had it. That is the level of bigotry, ignorance, and this toxic behavior that we cannot keep denying overshadows us as a people.

Visibility: The Afro-Arab, Black-Kuwaiti Perspective

MS: And that’s not okay. It erases you, and erasure is the primary tool of the oppressor. Just look at Palestine and the militant levels of violent effacement they’ve encountered at the hands of the Israeli oppressor—a plight that we can all collectively, as Kuwaitis, sympathize with and have actively mobilized against. How about the invisible minority here that we continuously erase? If you’re in a position of privilege then you can afford to take the time to understand ‘othered’ perspectives.

CDT: [Regarding visibility], when [I] was growing up, the only person that I had to look up to on mainstream television in Kuwait was Oprah. She was a staple in our household. Seeing her be a person of agency, being one of the richest people now, and having a hit television show and then her own network, it all made me think that I could do it. But why wasn’t there an Afro-Arab or a Black-Kuwaiti that I could grasp onto? The more I couldn’t see myself, the more I drifted even further [outside my own culture]. If you remember, there was a time during the 80s and 90s in Kuwait after the Gulf War [1990-1991] when a lot of young Kuwaitis were getting into African-American culture—wearing Timberlands, Fubu [American hip hop apparel company], flat caps, and having names like ‘Fifty’ and [enjoy listening to] Tupac.

People didn’t understand this, but for the black community [in Kuwait], we were imitating a black people that had agency and borrowed their swag, empowerment, and culture. [We noticed] the respect we [received from other Kuwaitis] for having [black] American [swagger], rather than being treated like an equal and of the [Kuwaiti] people, as we are. So we started perfecting our American accents, which for me came at the cost of my Arabic. But now that I want to advocate for Black-Kuwaitis—I’m going on national television, I’m doing these interviews with national [publications]—I have such a complex about it because I’ve realized that my Arabic isn’t perfect, [which will further everyone’s perception of me as an outsider], and now they’re going to discard what I’m saying. But what did you expect me to do, I was dealing with it in my own way.

MS: You were coping with these immense questions of identity and belonging. I can completely sympathize with you on that front as well. Regarding feeling like a ‘third culture kid,’ I too moved abroad at an early age, and then coming back here [to Kuwait] and having to absorb the culture and the language again at a later stage of my development truly made me feel like an outsider because my English language and comprehension skills far exceed my Arabic. The stigma for both—in certain communities you’re penalized for not speaking Arabic as well, and in others you’re shunned for not speaking English. There’s a lack of communal encouragement and support…

CDT: Yes, I was coping. Yeah, and it’s a… to be honest, it’s more political as well that we’re creating this divide between the ‘other’ and ‘Kuwaiti,’ the more that we will find ourselves splitting hairs, which I don’t see stopping. Again, who is the ‘original Kuwaiti?!’ This came from a place that existed in-between.

MS: Yes, these arbitrary, ahistorical placements and terms still hold weight in a place like Kuwait, and this is coming from someone who comes from a majority voice community. The fact of the matter is, without exception, Kuwaitis migrated here from elsewhere—wherever this elsewhere may be.

CDT: Yes! We are a country of migrants. And people will rise up and get so patriotic and take offense at that. It’s simply stupid to deny it. [Stressing on these divisional hierarchies], what are we afraid of? [The need to hoard because of the depletion] of resources? But these people [non-Kuwaiti migrants and expats], were brought in to retrieve said resources that we now have. It makes me angry because it makes me think of my grandfather who was a pearl diver. People of many different ethnicities were brought on the ships. But there were an exceptional number of black folk on those boats as well. So that, [in Kuwaiti history], is considered the golden era. We [Black-Kuwaitis] were rightfully a part of that era—retrieving pearls from the Gulf—we were part of building that history.

And now, similarly, we have a large community of [non-Kuwaiti] migrants working for extremely low wages who are being subjected to the harshest conditions. The amount of reports in national newspapers covering stories of maids getting raped or killed—the most infamous case of one domestic worker being shoved in a freezer, and another being pushed down the stairs to her death. And from that we turn around and we go, ‘we don’t have a problem.’ Why don’t you see that the same behavior [against migrants and expats] is being applied to a different group of people [minority-voice Kuwaitis]. We keep moving on, but unless we address the truth of our behavior there is no way I see Kuwait improving. We can do better. My heart will always be in Kuwait.

Don’t see my criticism as [resolute and unbudging], I too have to enact conscious change. I too need to correct myself and stop using certain phrases [that may be derogatory against a certain group of people]. Like when things are dramatic, I too say, ‘weeh, chyna filim Hindi’ [oh, this situation is as excessively dramatic as an Indian film plotline]. I need to change my own language too.

MS: You’ve written something previously that caught and has yet to release my attention: “Ps. I know I’m fashionable right now, my ‘complex’ existence is all the rage, I tick a lot of inclusivity boxes, but I am a person…and I’ll be here as I am when the fad is over.” Can you elaborate on that? And by extension, do you feel like you have to navigate a liminal space of negotiation when attempting to open dialogue with extremist perspectives on race, gender, nationalism, etc.?

CDT: I think we need to do it in our media. I think between ourselves, we need to hold each other accountable. And we need to [create] a culture that welcomes open conversations. I understand that people are scared because when you’re being called out it’s very [disorienting]—there’s a lot that’s shifting within you, foundational changes that make you feel like you’re breaking, like you’re wrong and bad. But all it is is addressing an element that isn’t good that needs changing. And if you have the heart and the courage to change, you can keep all the things that are truly worth keeping and that you love about yourselves the best.

What Kuwait and the region needs is an example of that. I think so many times when people in the region become allies—they disappear. They do all the research and then they reemerge as this all-knowing being. But, it is not truthful to the process of educating and improving oneself—this mystical way of disappearing and reappearing as all-knowing is not realistic. I want to know—and this is a conversation I’ve had with [Kuwaiti social media influencer] Ascia as well—how can we have this conversation and show people what a conversation like this looks like? No one will [incriminate you for making attempts to build bridges]. Show that you are making the change, that you are proud of that change, and you are working consistently on that change. A great city does not get built in one day—similarly, neither does a great person. We have that mentality [in Kuwait] that it takes a village to raise a child. So, instead of having one voice let’s allow for dialogue between communities.

MS: On that note, what’re your thoughts on this long overdue campaign against the harassment of women in Kuwait, in regards to both awareness and law reform?

CDT: To be honest, I’m worried. I’m worried because I don't trust the justice system in Kuwait. And I say this because I don’t see those in positions of power reflecting the people’s voice. As long as we have that [divide and] lack of understanding, and we’re not able to listen and be educated or be open to feedback from other communities within the region, I don’t see how we can make decisions that are not based on protecting those who are already in a privileged position—covering-up and preserving one’s reputation, which is an act that is not always in line with what is just.

We need to stop all of this wasta business [nepotism, clout, ‘who you know’], because it’s always not for the benefit of the underprivileged, but it’s the trading between the biggest and most privileged people. There are, in my singular experience, two individuals who sexually harassed me and who are still walking the streets today, have been married, my family knows them. I’ve seen one of them many years ago, because Kuwait is so small, most of us are forced to face our abusers in public situations. And this wasn’t a shock to anyone, this guy is known for being an abuser. As for me, I was shunned from my group of friends, my family–especially my brothers–were angry with me for putting shame on my family. While this person is still considered a friend of my brother’s. While the other guy has gone on to target other women. In my friends group, everyone has a similar story to mine, because there is no open dialogue and no one we can speak to about these issues because we fear that we will be the culprit, we will be the person blamed for going to a certain place at a certain time wearing a certain thing.

The grooming that happens—[Kuwait] is still a society where men can run free, and women are expected to be back home no later than 10 pm. What are the guys doing roaming around the streets that late? There is so much toxic masculinity and so many sexual predators that are walking free in Kuwait that have either bought off or come from a prominent family and can’t be legally touched and they have targeted someone who doesn’t have the means or agency. Or the victim will keep quiet out of sheer shame and carry the weight of this crime committed against them to the grave, or they’re forced into silence after being forced to marry their abusers. We are willing to put women on the firing line to protect men.

So these help lines or hotlines for victims, I feel, were established because of international pressure that was put on the region post the international ‘Me Too’ movement to make a stance. Black Lives Matter—a similar situation, everyone had to make a stance. We’re still on the surface level. There are so many conversations that we’re not having, and until we have those difficult conversations, I can’t trust a help line or visiting a police station where those who should be helping me are from prominent tribes and would rather protect my abuser who happens to be a relative.

Why don’t we believe these women? How many of them must suffer and deal with trauma in silence? We don’t even have the resources to help with said trauma! Therapy is still not accessible to all in Kuwait or the region. We need the resources to help with people’s mental health. We’re meant to be a majority Muslim people, there are so many moral issues we claim to stand by but I have yet to see practiced.

MS: To watch us [Kuwaitis] still cripple under the pressures of arbitrary social stigmas, what’s considered ‘aib, and shy away from mental health and seeking therapy—from an educated people—is baffling…

CDT: There’s so much [to unpack], what do we cover! I see so much improvement, if we could just be proud of ourselves as a people—as a mixed people.

Creative Industry

MS: You describe yourself as an actor and theatre maker. Can you tell us more about that, the work you’ve done in the past and work you’re currently involved in—from Twelfth Night (play), Make Me Up (horror/comedy show), Doctors (BBC TV series), The Witcher (Netflix series)…?

How did you start in this industry, how did you start acting and booking roles—did you ever feel like you were profiled into certain roles?

CDT: You’ve got really good questions! I started acting in school, as the drama program got introduced into the curriculum. Because I went to a British school in Kuwait the curriculum brought with it a bit of Western influence—Western pizzazz. It benefited me and encouraged me to not only act, but also to write, which combatted the lack of material due to [Kuwaiti] government censorship of a number of creative, dramatic materials not allowed in Kuwait. On the one hand, we worked a lot with Shakespeare and other heightened texts, or we experimented with my own storylines from my life, from what I watched on TV.

I wanted to talk about what happened in the private space, so I started writing shows that reflected me and those around me—our humor, love, issues we dealt with. This started for me as early as playing with Barbie dolls with cousins and reenacting storylines then. During drama classes, I realized I can create from scratch—from planning site specific settings outside our classroom to sewing costumes. I went into my grandmother’s shed bel satah [on her roof] and found a whole bunch of materials and equipment from the Gulf War—like army and camouflage fabrics, and also stored food and snacks in preparation to go into hiding. My grandmother had an old sewing machine, so I started to figure out how to sew together and create costumes from all this material.

From there, I was ready to set up another play for school the next day—I had the costumes, setting, lines, all of it! After that, I joined an amateur theatre group and they performed at camp Doha, Arifjan, and other places in Kuwait—kind of on a mini tour. The cherry on top was seeing Sulayman Al Bassam [Kuwaiti playwright and theatre director], whose work is a great driving force for me. I cannot recall his name enough. The first time I saw women on stage as fully formed three-dimensional characters was during one of his theatrical works. The way they had so much command of their presence, posture, ticks, and voice! Recognizing the mechanics of a performance, but not being able to name the techniques was what drove me to learn the skills it takes to perform like that. I wanted to be able to transform so much that you would believe I was my character. Also, there were so many actors like Leonardo DiCaprio, Nicholas Cage in Face Off, Will Smith—all these staples that inspired me.

So I applied to Liverpool [LIPA] despite my terrible grades in high school. I had an English teacher, Mr. Andrew, who wrote me my letter of recommendation. When I read it, I cried. I was so embarrassed at the time. I felt like everyone was starting to spread their wings and make their career choices. But I was stuck. They were the worst years for me… So Mr. Andrew was my saving grace. His letter was so strong that I got an unconditional offer to go to Liverpool [LIPA], assisted of course with my self-tape [an audition that the actor films remotely]. And now self-tapes are the bane of my life, haha!

There was so much culture shock and I wasn’t able to come home for so long because my family couldn’t afford me going back and forth. I didn’t come from a well off family—I’d say we’re between middle and working class because we were definitely struggling. And here I was wanting to go to drama school, as well. Not only that, but my mother’s first reaction was, “shbigoloon el nas [what are people going to say], what am I going to tell people [about your unconventional career choice]?” I remember her telling me once, “even Hayat Al Fahad has a day job!” But I didn’t want to work at a day job, I wanted to pursue acting full-time.

So finally, I got signed during my graduation year [from LIPA] by an acting agency in London. Thank goodness, I’ve been working [as an actor] ever since. I’ve also had odd jobs that have helped me along the way. When I first started, I was working as a waiter for a catering company, while also modeling at the time. I’ve had a strong work ethic ever since living in Kuwait really. However, I did notice the difference. At age 21 in the UK everyone else around me already had massive work experience—coffee shops, waitressing, etc.—but coming from Kuwait, I didn’t know how to explain to them that as a Kuwaiti woman I’m not allowed to work at a cafe because my mom wouldn’t want certain people seeing me work at cafes or restaurants. She said to me that I’d be lowering my status. So my work ethic in Kuwait extended to all the extracurricular activities like sports and acting that occupied my schedule.

After coming back to Kuwait around 2013-2014, I founded an art company with a friend of mine that facilitated creative projects. Despite trying our best, we realized that we can’t build on an infrastructure that isn’t there—we were challenged with this task, which filled our time with administrative work when all we wanted was to form a troupe of people that would come in and play. With any creative endeavour, you need space to be able to imagine. But here I am sitting, against my will, writing email after email, contract after contract—as a dyslexic! It broke my heart. During that time, I went back to London for an acting workshop because I recognized that I needed to maintain and top-up my skills.

The workshop was with a theatre company that I’ve been watching for ages and right on the spot, they asked me if I wanted to join them. So this is in 2015, I was extremely excited, and packed my bags. Actually, before I even left Kuwait, my dad was diagnosed with terminal cancer. I knew that upon leaving that anytime now, my dad was going to pass away. So I had to be strong as hell to be without family, in a new place doing something that was challenging, not only to my culture, but also having come from a background where I was struggling financially.

After my father passed, I decided that I was going to do what I promised him. He always said, “Colette, dream. Dream big and don’t look back.” He always warned me against coming back for him. Funnily enough, [his memory never faded,] every time I had a business meeting in Kuwait, someone would recognize him from somewhere, and hold him in high regard. When I came back to Kuwait after drama school (2014), my mother had already moved to the United States. So any favors that came my way, came from people who knew my father—an immigrant in Kuwait. So it just has to be recognized—the efforts of so many immigrants living, working, and contributing to Kuwait and the region.

MS: So what kind of roles did you get? Were you ever typecast?

CDT: At the beginning, when I was 21 or 22, I got: African slave, refugee asylum seeker, black-other, Eatsern African, etc. In the UK it was really hard because Afro-Arabs are not on the map, you’re not represented. So you’re kind of black, but the black culture they were accustomed to was Black-British, Black-American, maybe Latinx, and that was the extent of it. So I was seen as something ethereal or regal—very different. I began to understand that view of me after a teacher of mine told me I was slightly standoff-ish. That confused me at first, but realized this came from my Arab-Muslim culture of maintaining distance [out of respect] and social etiquette. That etiquette [in Britain] was tied to something that resembled the kind of behavior expected when meeting the Queen! So I was learning how to merge my Arab identity with the industry.

Then I was invited [by the Shakespeare World Stage, the Globe Theatre] to translate five of Shakespeare's sonnets to Kuwaiti-Arabic. I don’t have the skill to translate heightened English text to the Kuwaiti dialect. Yet, at the time, I felt like I had to say yes to every opportunity, so I turned to my mother for help. She promised she’d help me do it and I’d learn it the way I learn songs.

So the process involved me explaining to my mom what the English Shakespearean lines meant and she would come back to me with a sonnet she created out of the Kuwaiti dialect. She helped me learn it phonetically, and I went on stage and did it! It was the biggest lesson of my life. I knew then that I wanted to start participating in my identity. And I have to try. But I was hoping there weren’t any Kuwaitis in the audience in case I made any mistakes, haha!

In a situation where I feel like I can’t be of the people, [I don’t belong]… ugh, excuse me I’m getting emotional now… I don’t feel accepted. I’m not an African who grew up in Africa. I can’t go up [on stage] and speak French or whatever, that’s not where I’m from. And here I was, given this rare opportunity for someone to ask me to speak, the best that I can, in the language I grew up with. So maybe it wasn’t perfect, but it was from my heart, and my mother helped me with it. And it brought me so much pride and purpose. And I said to myself that day, “I don’t care what anyone says. I’m half-Kuwaiti and half-Cameroonian, and I grew up in Kuwait.” All of my work that I make is gonna come from that place, and I will deal with people’s reactions from that space.

From then on I started building Dreamer, my solo-show, in my head. I asked myself, “What do I need to address?” Dreamer is about black women in Arab society. I got funding for it from the Arts Council of England. I went into research and development in the Summer of 2019. I then was in residency there when developing it. I had scenes depicting my upbringing in Kuwait—Friday zwaras [family gatherings], time at the hair salon, Girgi’an [mid-Ramadan celebrations], etc. One of my lead characters is a ‘khadama’ [domestic worker], and I’m using my father’s old photographs on a projector from the 60s. My costumes include dara’at [women’s colorful traditional dress, ‘kaftans’]. I also show my grandfather performing with his firqa [band, performing traditional Kuwaiti music] on television. And also Kuwaiti women waiting on the shore for the men to come back from pearl diving.

It’s my world. And I hope that it shares, or rather, is relative to many—the Black-Kuwaiti specific story. The people on my team working on this project are East Africans that lived in Saudi Arabia, Black-Lebanese, an Iraqi friend, and an amazing musician from Ghana. We are trying to reconnect and find stories and songs of empowerment in black beauty, including the necessary conversations and issues we have to confront. This is a play where I have put all my hopes and experiences into, as an artist does—all your heart into your work.

Afro-Arab: Cover-Personality

CDT: I’m so impressed by your initiative, and Khaleejesque’s incentive to have this real conversation. I mean, when I was on the set of Domina [TV series] in Italy, everyone around me was buzzing with excitement about the international magazine coverage that I would be receiving. But nothing compares to or replaces a publication from your own country wanting to interview you. When you don’t see many people like you on magazine covers in the region.

MS: We’re addressing our own shortcomings in doing so as well.

CDT: Many years ago, Khaleejesque put out a question asking: What do you want us to cover? And I remember writing that I can’t own that I’m Kuwaiti in fear of offending full Kuwaitis that I too identify as Kuwaiti. So to be in this position many years later, it just blows my mind! I’m very honored to be a part of this.

MS: We’re honored that you agreed and have shown us an impeccable work ethic.

CDT: Just bear with me one second, I thought I would do some readings. Would you mind?

MS: Please go ahead!

CDT:

www.instagram.com/cdtchantcho

www.instagram.com/lensz___/