This summer, I sat down with Saud Al Sanousi, the playwright of Kuwaiti musical Muthakarat Bahhar. It was his inaugural venture into the art of theatre—with the generous support of Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmad Cultural Centre (JACC), where his new office resides. I had a lengthy conversation with Saud about what it means for cross-cultural cooperation to take place in Kuwait between creatives from different backgrounds and professions, as well as his own journey as an inspiring writer to so many in the region and beyond. His novel, The Bamboo Stalk (2013),has been translated into eleven languages from the original Arabic, while his formerly banned novel, Mama Hessa’s Mice (2016),has recently been published in English. Currently, Saud’s latest novel, Naqat Salha (2019), which translates to ‘Salha’s Camel’ is his first attempt at a narrative written from the perspective of a leading female character. Join us in this intimate conversation with young Kuwaiti novelist, Saud Al Sanousi.

Abrar Al Shammari: Tell us about your daily routine.

Saud Alsanousi: I don’t have a regular routine. I usually read on a daily basis, and if I’m lucky enough and inspiration strikes, I engage in writing. Recently, for the past nine months now, I began to write articles for Zahrat al Khaleej magazine, a daily habit of writing which has helped me practice writing with great diligence. In the past, being able to write was a practice that heavily depended on my mood. Now, I’m committed to a weekly magazine, so I’m bound by a deadline and specific schedule. Being disciplined in such a way with writing has helped me write more and with determination. Even when it comes to novels, I’m no longer waiting for the mood to strike.

A.Sh.: What rituals motivate your ability to write?

S.A.: I understand that my answer might come off as frustrating, but I don’t have any rituals so to speak. However, before I began to write, I was an avid reader who enjoyed visiting the homes of world renowned novelists on my travels. I’ve been to Victor Hugo’s house in France, Kawabata and Mishima in Japan, and Saramago museum in Lisbon (Portugal) in order to take a closer look at their private worlds—the desks on which they penned their works. I had this desire to familiarize myself with their writing habits. When I started writing, I had no particular habits or rituals. I would write in the office, or in the airport, or in my hotel room, or even while cycling where I voice-recorded my ideas.

But if there’s anything worth mentioning that I do while writing, it would be listening to music. Only music, no lyrics. Music helps the flow of my writing. Each of my novels is closely related to the specific genre of music that I was listening to while writing. For example, I listened regularly to a Filipino song while writing the first half of The Bamboo Stalk. While for the second half of writing the novel, I periodically listened to samri music [a traditional Khaleeji genre of music]. This proves the inspirational quality of music; the music I listened to while writing has a connection with the time and plot lines of my novels. For me, music goes hand in hand with writing.

A.Sh.: Beyond being an avid reader, when did you start to view yourself as a writer?

S.A.: This is a difficult question that I don’t particularly have an answer for. I didn’t become a writer overnight, nor did I deliberately choose to take up writing as a profession. As a child, I began to write privately. I wrote my reflections in a diary, and what I considered to be poetry and short stories. At the time, blogs were a popular platform for amateur publishing, and I continuously contributed under a pen name. Blogs spared many of us the hassle of publishing in newspapers where articles are heavily edited, or shortened, or published a year after their conception. Blogs made up for and expedited this lag and gap in traditional publishing. Soon after, I began to write for newspapers, but not professionally and with no column of my own. I have no idea when I officially became a writer. I did carry a notebook with me since I was nine. Perhaps I became a ‘true writer’—beyond writing in my notebooks—when at the age of 13, I published my first story.

A.Sh.: What childhood memories would you say have contributed to your literary writing?

S.A.: The family home—my grandmother’s house. I’m so lucky to have lived and been raised there. Everything I have achieved thus far, I owe to that home and my memories there. Such a home is rare nowadays. In that house, I lived with my grandmother and sixteen paternal aunts and uncles. They all possessed rich personalities that were vastly different from the next, and they told the most intriguing stories. The most intriguing of those stories came from my grandmother who was a true storyteller. Her stories revolved around Djinn, humans marrying Djinns, talking trees and reptiles, and so on.

These memories stimulate my imagination, and thanks to them, I made a point of connecting these memories and tales of an older generation to mine in the present. During the day, I played Atari games and on Sakhr computers with my peers. However, in the afternoons, like those of an older generation, I would go bird hunting. These hunting trips helped me learn the names of different birds and fish species. And all this, I learned from the family home. Many might argue that I write about topics that I never experienced myself. They might be right, but it’s all engraved in my auditory memory. I intently listened to stories from my grandmother that began with: “She went to Mecca on a camel’s back.” Today, I find it difficult to discern between my own distinct memories and those of my grandmother and father. It is those familial and childhood memories, in addition to reading, that have forged my character.

A.Sh.: Who are the writers that contributed to your literary development?

S.A.: No one specific. In fact, I would say that my entire library has contributed to the development of my writing skills. From time to time, when I stand before my bookcases and read the titles on the spines, I remember all that I had learned from each of them. I learn from everything I read. For instance, I learned a lot from the late Kuwaiti author, Ismail Fahad Ismail—from both his writings and from our personal meetings. Conversations with Ismail gave me the chance to unearth more meaning from his writings and the methodology of his writing. Ismail is exceptional. I definitely refined my own skills from reading Ismail’s work, but also benefited immensely from my direct relationship with him.

But on a personal level and from indirect contact, I learned from Najib Mahfouz’s writings, and from reading the works of many other great writers. The current generation in Kuwait is very lucky; we have something that is missing in the Arab world: the interconnectivity of multiple generations. It was easy for any young writer to meet and connect with renowned Kuwaiti writers like the late Ismail Fahd Ismail and Leila al-Othman. Within the literary scene in Kuwait, there is no communicative rupture or discriminating hierarchy between a prominent writer and an up-and-coming one. Leila al-Othman established a biannual award aimed to recognize the talent of young writers, and among its outstanding recipients were, Istabraq Ahmad, Youssef Khalifeh, Mays al-Othman, Bassam Mosallem, and Abdullah al-Husseini. When she travels, Leila carries with her three copies of my novel, The Bamboo Stalk, and three copies of, A Soundless Collision by Bothayna Alessa with the intention to distribute our books. There is a specific brand of affection there, a communal desire for the representation of literary works produced in Kuwait.

A.Sh.: Can you further elaborate on why you regard Kuwait’s literary scene as an exceptional case?

S.A.: First, Kuwait is a small country. Therefore, so is the community, its platforms, and its events familiar and habitual. Such an intimate scale empowers the kind of bonding that made it easy for me to connect with Ismail Fahd Ismail at the Althulatha Cultural Forum, or at his office, or in his private home. This is also true when it comes to Leila al-Othman. Second,

these literary pioneers in Kuwait lack the conceit, or do not impose or reinforce highbrow culture that is rampant in the academic scene. Exceptional Kuwaiti writers of an older generation do not view themselves as “professors.” The relationship between us [younger and older generation of writers] was never a “professor-pupil” one; rather, a lateral friendship of exchange has developed between the two generations. Ismail would get upset when someone would say, “Saud is your student.” His reply would be, “This phrase is offensive to both Saud and myself. I don’t consider myself as his teacher. It is not my role to teach or to make a duplicate of myself.”

A.Sh.: You are now world-renowned, and your novel, The Bamboo Stalk, has been translated globally…

S.A.: I am renowned in the Arab world and, thank God, I have accumulated a vast Arab readership. The novel has been translated into 11 languages, but all these languages do not make me a world famous writer.

A.Sh.: Do you consider this fame a challenge or obstacle that may prompt you to make compromises or sacrifices in your work?

S.A.: On the contrary, it has strengthened my faith in my locality and local community. Also, a growing readership and popularity gives a writer the incentive to be more aware and selective with what he or she says—a larger audience holds the writer accountable for what they say. For that reason, I maintain the desire to stay within my locality and to justly reflect my locality in my writing. As far as writing about one’s local environment is concerned, there is for example, the Cairo described in Najib Mahfouz’s writings, or Rasul Gamzatov’s Dagestan, and Al-Tayyib Salih’s Sudan. I strive to do the same for my own locality, Kuwait, in my writing.

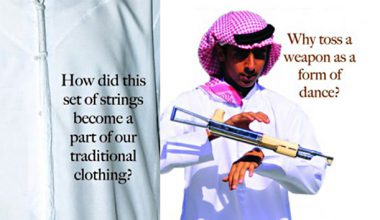

After receiving an international prize in the States, it made it a more enchanting experience to have a deeper discussion about my writings with a foreign reader who is curious about a character of mine like, Mama Ghanima, and her boshiya [traditional black veil], and how she wears it, and her samri dance, and the burning of her incense. When writing about my local culture, I find it easier to write for a curious reader who is unfamiliar with Kuwait. A writer might wrongfully believe that for him/her to become known in Egypt, he/she must write an Egyptian novel. That’s not true. Egyptian readers are self-sufficient. They want to know the writers by their local environments. When we read Kawabata’s work [Yasunari Kawabata, Japanese novelist], we might be curious about, for example, the finer details of the Kimono garment, or his way of eating prawns, his routine walks on the maple hills, and any other cultural details that are particular to a specific place and time.

Having a readership outside of Kuwait motivates me to familiarize them with local issues. For instance, a novel about the lived experience of a half-Kuwaiti, half Filipino living in Kuwait. The socio-cultural reality of the character could be read as a novel about the expereince of a half-Arab, half-Amazigh, or a half-Palestinian, half-Jordanian, or a half-American, half-Mexican. The topic applies and is relevant to any place.

A.Sh.: What is your intent or your main objective when writing?

S.A.: It could be a selfish one. Writing is where I find my sense of self, and the only means of expression that I have. If I was able to master the oud [Arab musical instrument, similar to a lute or mandolin], I don’t think I would’ve picked-up writing as a means of artistic expression. And if I am, in fact, a good writer—I, of course, cannot be the objective judge of my own work, as it is my means to affect change in myself and others. In addition to that, writing allows me the perspective to live several lives and endless experiences. Milan Kundera says: “The characters in our novels are our own unrealized possibilities, even if sometimes they are bitter.” There is a younger generation of Kuwaiti writers that are considerably recognized. And what has made these writers so distinguished is their writing, which elaborates on the localized, Kuwait environment—a geography that seldom appears in literary works on an international scale. That said, I believe that Kuwaiti literature stands a chance to compete with literary works on a regional and international scale.

A.Sh.: Let’s talk about character development, and how you get into character?

S.A.: I can never truly live the experience, but I can get in close proximity to it. For my novel, The Bamboo Stalk, I traveled to the Philippines and lived in a cottage for a while. When I was heading back to Kuwait, while in the airport, I attempted to take on the perspective of the half-Kuwaiti, half-Filipino—becoming more attentive to and observant of certain things and people’s demeanors. With a similar approach, for my character, Fawziya, from my novel, Mama Hessa’s Mice, I had to put myself in the shoes of a diabetic blind woman. To delve deeper into the experience of such a woman, I first spent a whole weekend blindfolded. As for Fawziya’s diabetes, I frequently visited the doctor to inquire about the disease and its risks. As for her position as a woman, it was also quite difficult for me, as a man, to fully impersonate a woman’s narrative voice.

A.Sh.: Have these experiences changed you?

S.A.: Of course they have. They have helped me understand the world and others beyond my own scope and individual perspective. I’m not the same Saud I was before writing The Bamboo Stalk. Writing gives me the chance to live elsewhere and experience ‘otherness.’ For that, I’m not only a writer, but also a critic.

A.Sh.: What character posed the greatest challenge to Saud Al Sanousi?

S.A.: Good question. My character from The Bamboo Stalk, Jose Mendoza, because he is extremely different from who I am. We may agree on some issues, but he neither resembles me physically nor in character. He posed a great challenge for me, even in matters concerning religion. So when approaching Jose, I tried to rid myself of who I am as Saud and my religious heritage while visiting places of worship in the Philippines. It was rather difficult.

A.Sh.: Is it possible for a writer to reach fame or to become reputable in their distinct field without being social?

S.A.: Writing is a peculiar affair. One must do both: seclude themselves and mix and mingle with those around them, simultaneously. Without this balance, extreme seclusion will marginalize you, while over-socializing will flatten your perspective and make it shallow—a copy, just like everyone else, both in the virtual and the real world.

A.Sh.: As a writer who has continuously dealt with censorship, have you ever exercised self-censorship or censored your own writing?

S.A.: I’m grateful to the relevant authorities for giving me my freedom. I didn’t necessarily write freely prior to my experience with censorship authorities. A sense of freedom in writing came after my dealings with governmental control of my content. Before then, as a preemptive measure, I used to twist my words to make my ideas elusive—so as to convey it without explicitly declaring it. I was quite convinced that governmental censorship would suppress and misinterpret all writing. Since my work would be censored anyway, that conviction gave me the freedom to say whatever I wanted. "Say what you want," was a piece of advice I had gotten from Kuwaiti writer, Abdel Wahab al-Hammadi, when I was writing Mama Hessa's Mice. However, I always exercise self-censorship; and by that I mean, I am selective about the issues that I bring up—so as to avoid misrepresenting certain topics.

A.Sh.: Can you give us a brief overview of your writings?

S.A.: From my published work, Mama Hessa’s Mice is the closest to my heart. I write what I wish to read, as if I were writing for myself. Right after that, in 2015, I started writing a fantasy novel set in pre-oil Kuwait. It was a long one, with an array of characters and lots of sub-narratives and side stories that eventually converged with the main plotline. For a while, my purpose for waking up was to work on it. No doubt, I got more and more attached to all of the characters, and I wished that writing it would last forever. After two years of writing, I published, Hamam Al Dar (Pigeons of the House) in 2017, before I resumed working on that fantasy novel. Two years later, Naqat Salha, was published. I will return to that fantasy novel once again. In fact, I love long books, whether I am reading or writing them, because it’s within these lengthy works that I am able to create a certain intimate bond with the characters. By the same token, books that take a while to read, like Naguib Mahfouz’s trilogy, create the same bonding effect (that trilogy took me two months to read).

This kind of relationship (between reader/author and characters) is an observational one: I intently record their transformations, minor mood swings, and thinking processes. Similarly, my works are mostly based on research. For instance, to write a short novel like Naqat Salha, I immersed myself in publications that documented the Kuwaiti desert and camels. It was a thrill! On the other hand, the novel that I’ve been busy working on since 2015, has given me the opportunity to study more on Kuwait’s pearl diving history, the sea, the culture of sailors, Kuwaiti women’s position at the time, the structure of the mud houses, the old markets in Kuwait, the islands of Kuwait, the battles that were fought, and the walls that were erected around the old city of Kuwait.

The research process is a stage of writing that I enjoy very much, and I am always disappointed when it’s over. It doesn’t matter if I haven’t included these details in my novel, I’m glad I have absorbed the knowledge for myself.

A.Sh.: Do you have any particular advice for writers in the Arab Gulf and beyond?

S.A.: A writer is a writer, no matter what his/her nationality is. I don’t believe I’m in a position to offer advice, but in my humble opinion, I would say to those who wish to write to read as much as you can.

A version of this article was featured in Khaleejesque’s September 2019 issue.

Words: Dalal NasrAllah, Abrar Al-Shammari

English Translation: Malak Al-Suwaihel

Interview: Abrar Al-Shammari

Images: Abdulaziz Kadhem Alballam

Art Direction: Mahjabeen Ahmedi, Malak Al-Suwaihel