Amira1 started her business, an independent coffee shop, at the age of 25. She would have started sooner, but her friends convinced her to wait. “Back then, we didn’t have the concept of local coffee shops,” she says. “They wouldn’t take it seriously.”

Amira is just one among many young female entrepreneurs in Kuwait who are pushing the boundaries of business and changing the meaning of work in Kuwait. “Women are steamrolling the entrepreneurial ecosystem here,” stated Sada, an entrepreneur and leader at one of the only enterprise accelerators in Kuwait. “I know several women entrepreneurs; their rate of success was faster than I have seen with many other male entrepreneurs.”

These young female entrepreneurs are making a powerful statement about the traditional forms of work that they are pressured to take. Layla, owner of a technology development business, poses the question that she would like to ask her parents: “Why would you be stuck with a job that wouldn’t be satisfying for you? That would be killing you?”

Since moving to Kuwait with my family last year, I have been blown away by the number of vibrant young entrepreneurs that I’ve met. Nora, owner of an online recruitment company, best describes our shared inspiration from other female entrepreneurs, “Just seeing the way that female entrepreneurs navigate the hurdles and challenges they are facing is inspiring in itself.” Even more inspiring, they are hungry for change: for themselves, for their families, and for their communities.

The establishment of the National Fund for Small and Medium Enterprises in 2013, followed by Fikra in 2015, have helped to spark the creation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem to support the growing number of young entrepreneurs. The National Fund intends to “build an inclusive, collaborative, and innovative ecosystem for entrepreneurs to lay the foundation for economic opportunities in Kuwait.”2 The Fund recognizes that small businesses are a “basic anchor for sustainable growth” in Kuwait and provides incubation, acceleration, funding and additional support services to Kuwaiti’s who want to start a business or expand an existing one. Fikra started in 2015 as a corporate social responsibility initiative by Cubical Services, offering free training and mentorship to young Kuwaiti entrepreneurs.

As a feminist economist I am trained to critically analyze and promote policies through gender-aware and inclusive economic inquiry. As a researcher, I have applied this focus to studying the impact of the promotion of female entrepreneurs across different regions and in countries, including Thailand, Sri Lanka, the UK and the USA. In Kuwait, as opposed to the other contexts where I had worked, it was the lack of an explicit focus on women in the enterprise promotion policy that was most surprising.

I have explored women’s entrepreneurship in many places. For the past 10 years, I have analyzed entrepreneurship as a tool for women’s economic and social progress. My work largely criticizes the entrepreneurship promotion among populations of women with few choices or freedoms. Such programs are often done in the name of “women’s empowerment,” and are backed by a widespread belief in transnational business and government entities that investing in women is “smart economics” with limited attention given to specificity of individual, household, and national contexts.3 Much research has now joined my own to confirm that these women-centric programs are short-sighted, incomplete, and often leave women worse off than before.

Kuwait provides a unique context for this work as the rentier state economy is subject to more control by the government than in other places. Combined with its small size, this means that Kuwaiti entrepreneurs must contend with a business market that does not operate with the flexibility and independence found in countries with more laissez faire economic policies. The National Fund itself represents an extension of the rentier state through funding nascent enterprises outside of the usual risk environment.

What I found in Kuwait was motivated and inspiring women determined to make changes to their communities. Compared to the promotion of microenterprise and microfinance among poor women who face limited alternatives, women in Kuwait are making specific choices to start businesses, lured away from traditional forms of work by the promise of greater independence and the chance to pursue work they are passionate about. Academics refer to this as the distinction between necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship.4 Globally, women are primarily engaged in necessity entrepreneurship, creating businesses primarily because of severe financial hardship in their households. These women struggle to find ways to earn money in environments where other opportunities for work are rare or where social norms limit the opportunities available to women.

Much of the knowledge available about female entrepreneurs derives from these economic development contexts. Developed country research largely focuses on “mumpreneurship,” the assumption that most women in these countries enter entrepreneurship in order to establish a balance of work and family responsibilities.5 Taken together, these two poles represent only a small part of the story that female entrepreneurs are writing around the world. By documenting and analyzing the experiences of female entrepreneurs in Kuwait, I want to promote a different conversation, one that isn’t rooted in hegemonic assumptions around women’s limitations. Kuwaiti women’s high educational achievements, access to domestic help, and numerous economic opportunities make them an ideal population to drive a new conversation.

Through my research, I have heard stories of inspiration, a passion for changing communities, and a desire to work in an environment that responds to effort and provides a space for personal and enterprise growth. In this, Kuwaiti entrepreneurs are reflecting the modern identities that are being absorbed by youth across the Gulf who want to align their work with their passions and are willing to walk away from the stability of public sector employment in order to do so. While the Gulf region is arguably the historical center for merchant and trade activities globally, modern entrepreneurship is serving new ways to solve community, national, and global challenges. In this, young Kuwaiti women are joining “a rising generation” in the Gulf who “have found a deeply socially conscious, often nationally proud expression in business ideas.”6

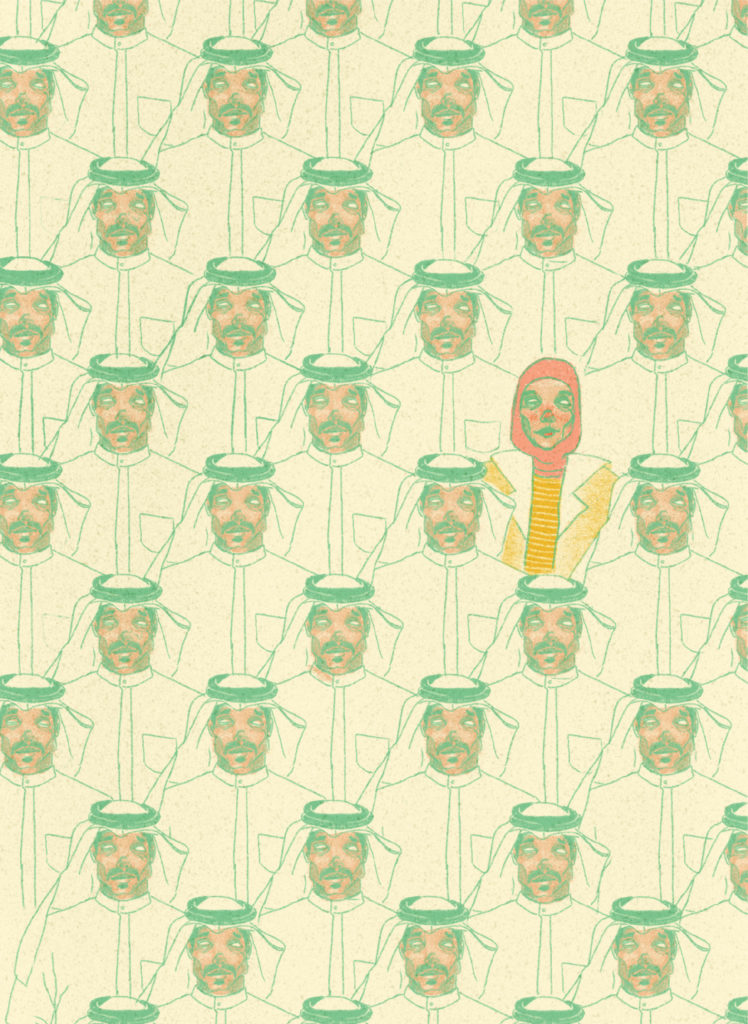

These young entrepreneurs are finding it difficult to operate under cultural and governmental guidelines that don’t yet reflect their values. Zara is an independent creative marketing professional whose family still do not know that she left her job a year ago to focus on her business. She explains that her family is just one part of the culture that needs to adapt, both to the new forms of work that are being established by entrepreneurs and the fact that females are leading this charge in Kuwait. “I think a huge majority of people are not used to seeing female entrepreneurs: opening doors, sitting down to meetings, leading meetings,” she said. “They don’t know how to deal with it.”

Many participants in my research have told me of the pressures their families impose on them to stay employed in the public sector. Amara, who opened one of the first independent coffee shops in Kuwait, has not been able to tell her family that she has taken a leave from her government job to focus on her business. Dalal, who’s business offers natural health and healing services, stayed in a job she hated for more than a year because of her parent’s request that she save more money before leaving. Multiple others have yet to leave their jobs in the government sector because of the pressure of their families.

Further resistance comes from the clients of women’s enterprises. The women shared many personal examples of client’s resisting working with women’s businesses. Refrains of “isn’t there a man we can talk to?” and “Why aren’t you at home?” are common. One woman resorted to using her male intern to speak with contractors even though he was not qualified.

In addition to the resistance of family and clients, this troop of female entrepreneurs find themselves unable to operate within the current definitions of work that are recognized by the government. Women running diverse types of businesses, from independent coffee shops to creative and technology services to those offering entirely new services to the country, often find that no registration category exists that represents their business.

“It was a complete shock” described one entrepreneur about her first trips to government offices. Her accumulated business experience “did not apply” to the demands of the government bureaucracy. “I had to retrain myself to deal with a completely different structure,” she said, which was the “number one hurdle” for her enterprise. Amani, an artist and interior designer, described her experience with government registration processes and their “lack of awareness of the creative industries and the business of the creative industries. Their understanding of business is more retail, and it is not suited for the creative industries.”

Despite the difficulties, these young women are determined to be a force for change. For many, being this force is exactly the responsibility of an entrepreneur. As we sat on the patio of her café, Amara described how entrepreneurship comes “from the desire to follow something and discover something. It comes like a desire and you want to challenge yourself to get it.” For Amani, entrepreneurship is the future for all Kuwaitis. “I believe that everyone is eventually going to have their own business,” she said.

Why is entrepreneurship good for the country, I asked Layla as we sat in her office near Mubarakiya. “I think because they want to build something that has value, that reflects on them,” she said. “I think that’s based in every human, that they want to build something that is adding value, within the country, within their work.”

There is one point where they all agree. “Anyone that goes down a nontraditional path can be considered an entrepreneur,” I was told by an inspiring young entrepreneur. “You don’t necessarily need to start your own business,” she explained. “An entrepreneur is someone who has a desire to build something for themselves, whether that’s a startup or a project within a country or just developing their business in some shape or form.”

To these young Kuwaiti women, entrepreneurship is determined by impact and impetus, not by profits. And they want their government and communities to build the role of such individuals in Kuwait. So far, they said, government efforts around enterprise promotion are falling short. “Invest in your country, build your country. That’s the messaging I want to hear. It shouldn’t be about money” said Sada. She explained that in her role at the accelerator, applicants that only express their business in terms of profits are not accepted. She explains that they are looking for people who have a “desire to build something, to create something, to help solve a problem.”

Young female entrepreneurs in Kuwait are making real strides in changing the economic and social landscape of the country. Cultural emphasis on stability over risk-taking and outdated government regulations are holding them back. Easing these restrictions are key to unleashing the creative power of this generation. As Zara noted, “If they are given opportunities, and have confidence in themselves, they can do wonders.”

Even without a specific policy focusing on them, young Kuwaiti women are integral to national economic diversification, community development, and individual empowerment. However, having many start-ups in an ecosystem where people are afraid to take risks threatens the ability of these women to succeed, and their failure will mean a great loss of the potential of entrepreneurial opportunities in Kuwait. Government regulations will take time to change, but the community and social barriers female entrepreneurs face can be addressed now.

The next time you find yourself talking to a female enterprise owner or as a customer in a woman-owned shop, show your support. In fact, start learning about what women-owned businesses are operating in your neighborhood and give them a try. Ask about women-led companies when you are looking to hire services. And if you are lucky enough to have a young, motivated female entrepreneur in your family or circle of friends, ask how you can support her, even if it means she will miss a few family gatherings or lunch dates.

There is an army of bright young women invested in developing Kuwait through their entrepreneurial spirit. Let’s not get in their way.

Notes

1. Pseudonyms are used in this article to protect the anonymity of the contributors.

2. From the 2016/2017 Annual Report. Available online at https://nationalfund.gov.kw/en/

3. ROBERTS, A. 2015. The Political Economy of "Transnational Business Feminism": Problematizing the corporate-led gender equality agenda. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 17, 209-231, CHANT, S. & SWEETMAN, C. 2012. Fixing Women or Fixing the World? 'Smart economics', efficiency approaches, and gender equality in development. Gender & Development, 20, 517-529.

4. HERNANDEZ, L., NUNN, N. & WARNECKE, T. 2012. Female entrepreneurship in China: Opportunity- or necessity-based? International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 15, 411-434, WARNECKE, T. 2014. Are we fostering opportunity entrepreneurship for women? Exploring policies and programmes in China and India. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 18, 154-181, CALDERON, G., IACOVONE, L. & JUAREZ, L. 2016. Opportunity Versus Necessity: Understanding the Heterogeneity of Female Micro-Entrepreneurs Policy Research Working Papers. Washington, DC: World Bank.

5. EKINSMYTH, C. 2013. Managing the Business of Everyday Life: The roles of space and place in 'mumpreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 19, 525-546, SHEIKKH, S., SIST, F., AKDENIZ, A. & YOUSAFZAI, S. 2018. Developing an understanding of entrepreneurship intertwined with motherhood: A career narrative of British Mumpreneurs. In: YOUSAFZAI, S., LINDGREEN, A., SAEED, S., HENRY, C. & FAYOLLE, A. (eds.) Contextual Embeddedness of Women's Entrepreneurship: Going Beyond a Gender-Neutral Approach London: Routledge.

6. SCHROEDER, C. 2013. Startup Rising: The Entrepreneurial Revolution Remaking the Middle East, New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

Bibliography

CALDERON, G., IACOVONE, L. & JUAREZ, L. 2016. Opportunity Versus Necessity: Understanding the Heterogeneity of Female Micro-Entrepreneurs Policy Research Working Papers. Washington, DC: World Bank.

CHANT, S. & SWEETMAN, C. 2012. Fixing Women or Fixing the World? 'Smart economics', efficiency approaches, and gender equality in development. Gender & Development, 20, 517-529.

EKINSMYTH, C. 2013. Managing the Business of Everyday Life: The Roles of Space and Place in 'Mumpreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 19, 525-546.

HERNANDEZ, L., NUNN, N. & WARNECKE, T. 2012. Female entrepreneurship in China: Opportunity- or necessity-based? International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 15, 411-434.

ROBERTS, A. 2015. The Political Economy of "Transnational Business Feminism": Problematizing the corporate-led gender equality agenda. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 17, 209-231.

SCHROEDER, C. 2013. Startup Rising: The Entrepreneurial Revolution Remaking the Middle East, New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

SHEIKKH, S., SIST, F., AKDENIZ, A. & YOUSAFZAI, S. 2018. Developing an understanding of entrepreneurship intertwined with motherhood: A career narrative of British Mumpreneurs. In: YOUSAFZAI, S., LINDGREEN, A., SAEED, S., HENRY, C. & FAYOLLE, A. (eds.) Contextual Embeddedness of Women's Entrepreneurship: Going Beyond a Gender-Neutral Approach London: Routledge.

WARNECKE, T. 2014. Are we fostering opportunity entrepreneurship for women? Exploring policies and programmes in China and India. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 18, 154-181.

A version of this article was featured in Khaleejesque’s September 2019 issue.

Words: Dr. Melissa Langworthy, PhD

Illustrations: Ruqaiya Abdullah Ali Al Balushi