From illuminated manuscripts and concrete poetry, to the 20th century movements of Cubism, Dada and Surrealism, text has been integrated into art for aesthetic purposes, and to articulate subjects such as the subconscious and to incite political change. It wasn’t until the 1960s that the Conceptual artists appropriated text into artworks as a subject in itself, the openness and ambiguity of language allowing the artist to become more creative in its use. Last year in its tenth edition, Art Basel Miami Beach featured several language-based pieces, ascertaining their commercial viability and popularity among fairgoers. Part of the reason why language-based art is well received by audiences is that it provokes ideas and thoughts that begin in the gallery or at a fair, and are left to linger in the imaginings of the viewer who is invited to draw their own interpretations and conclusions about a piece.

Lawrie Shabibi’s exhibition, Text Me, which ended July 21st, spotlighted new and seminal language-based pieces by seven contemporary artists from the Middle East, Iran and South Asia, surveying the ways in which the format, materials and placement of words in a piece affect their connotation. The group show featured works by Hala Ali, Aya Haidar, Behdad Lahooti, Sheikha Wafa Hasher Al Maktoum, Yashar Samimi Mofakham, Dariush Nehdaran, Muzzumil Ruheel and UBIK. Text Me comprised works in a multitude of mediums, ranging from photography to print, and works on paper to sculpture, and also installations, that test linguistic theories, prompt political and social enquiry, and explore the ambiguity of language through poetics and wordplay.

Hala Ali is a Saudi artist, based in Dubai whose works are a part of two series titled, What is to be Read, What is to be Seen and The Construction of Meaning. Ali analyzes text, language and its contextual meaning, crafting her works from various media in the form of installations. Her four works are comprised of a single statement, written repetitively with marker on strands of gum tape, which she then interweaves together, creating lines of text that run vertically and horizontally. Her pieces are a visual interpretation of the Structuralist theory, that words derive their meaning by the relationships they create when placed together in a specific structure, with respect to the rules of syntax. Ali’s works provoke the question, of whether language-based art should be read or seen, and if a distinction between the two is warranted.

Aya Haidar, a Lebanese artist based in London, whose language-based works focus on the Middle East, explores themes of loss, Diaspora and memory through story-telling. Haidar’s Al-Balad series are black and white photographs printed on linen of an old town in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, abandoned by its original inhabitants and since occupied by poor immigrants. Haidar takes colored thread and sews onto the photographs, highlighting the aging features of the buildings and street signs that together characterize the town’s history and its people’s identity. In The Stitch is Lost Unless it is Knotted, Haidar reuses two shirts worn by children from a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon, weaving lines of poetry between them, illustrating the realities of displacement and the harsh conditions in which the Palestinian refugees presently live.

Iranian sculptor Behdad Lahooti presented a series titled Chahanchah, comprised of pipes caste from bronze, taken from bathroom plumbing, and inscribed with cuneiform symbols from the Achaemenid period. Chahanchah is a title bestowed upon Iranian Kings and translates to “King of Kings”, referring to the Achaemnid period which was the height of the Iranian empire, and central to the cultivation of an Iranian identity. Lahooti juxtaposes the alphabet with modern appliances, critiquing the progress his country has made in the 2,500 years of development since the Achaemenid period.

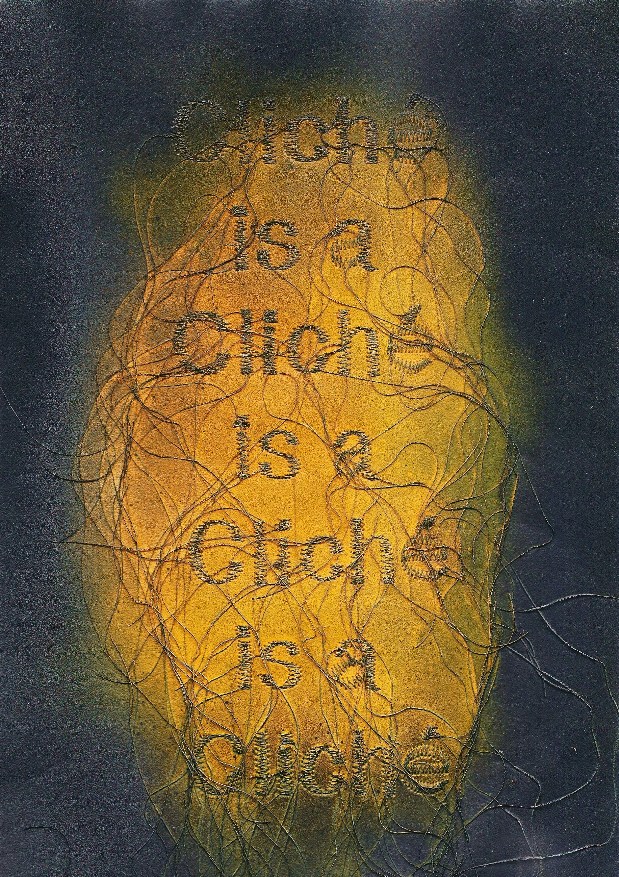

Emirati multi-media artist and graphic designer Sheikha Wafa Hasher Al Maktoum uses new media and a variety of materials to produce her cathartic and self-reflective works. Through her In Dreams series, she presented a neon sculpture that spells out the word unconscious with the prefix purposefully blinking on and off, illustrating the continued struggle between one’s conscious and unconscious. Her works on paper are embroidered with phrases such as “Check your ego at the door” and “Lower case “i” and “Beyond the Jagger”, suggesting that although pop culture and society promote egocentrism we should learn to keep our egos in check. Another work incorporates the redundant phrase “Cliché is a cliché is a cliché…” sarcastically highlighting how today the overuse of the word cliché has exhausted its original meaning.

Yashar Samimi Mofakham, an Iranian calligrapher and printmaker, presented works from three series titled, Paper Balls, The Existence and Siahmashq. In modern calligraphy, letters become the content of the artwork and are viewed as abstract forms rather than as transmitters of meaning. Mofakham’s unique approach to this style imbues his work with mystery and ambiguity. His Paper Balls series are photogravures on paper and silk screens on Plexiglas, which convey discarded pages of Farsi poetry crumpled into balls, signifying the present state of visual and literary culture in his country. Mofakaham’s Siahmashq and The Existence series are mixed-media compositions in which he repetitively layers words and letters, their meaning compromised for the composition and style of the works.

The Biker’s View series, by Iranian photographer Dariush Nehdaran’s resulted from having observed the way bikers on the city streets decorated their windshields with stickers, religious writings and prayers, calendars, and phone books. He documented the windshield as the lens through which each biker views and interacts with their surrounding environment.

Pakistani calligrapher, Muzzumil Ruheel's works are a part of two series titled What is Written and The Word We Live In through which he analyzes popular culture, questioning cultural and religious mores, history and media. What is Written is comprised of calligraphic works composed of pop English phrases and common sayings written in Arabic, which is used solely in a religious context in Pakistan. The Pakistani people do not understand the Arabic language otherwise, so the meanings of the words are lost on them, highlighting the difference between what is written and what is understood. The Word We Live In is a series of works in which Ruheel appropriates calligraphic script, layering words and phrases, to compose images of monsters. The words become illegible paralleling the meaning behind the title of the series, which is the distorting effect the media has on our perception of the messages it disseminates.

UBIK, an Indian artist based in Dubai, presented works from two series titled Rant #1 and 2 and ERGO. His works explore concepts of the absurd and existentialism, as well as the use of clichés. Rant #1 and 2 are composed of laser engravings on wood, and resemble memorial plaques, with phrases taken from his journal. The first of which can be understood to allude to the fall of capitalism stating, “One day you will run out of dark chocolates to place on your pillow” and the second referring to the artist’s predicament on leaving behind a legacy, “a legacy can only be left behind through word of mouth.” ERGO is a red flag featuring yellow text that recapitulates UBIK’s way of life, the design and title of which refer to communism.

Lawrie-Shabibi Gallery is located at Unit 21 in Alserkal Avenue, Al Quoz, Dubai, UAE. For more information visit www.lawrieshabibi.com

– Nadine Fattouh

Images courtesy of Lawrie-Shabibi and the artists