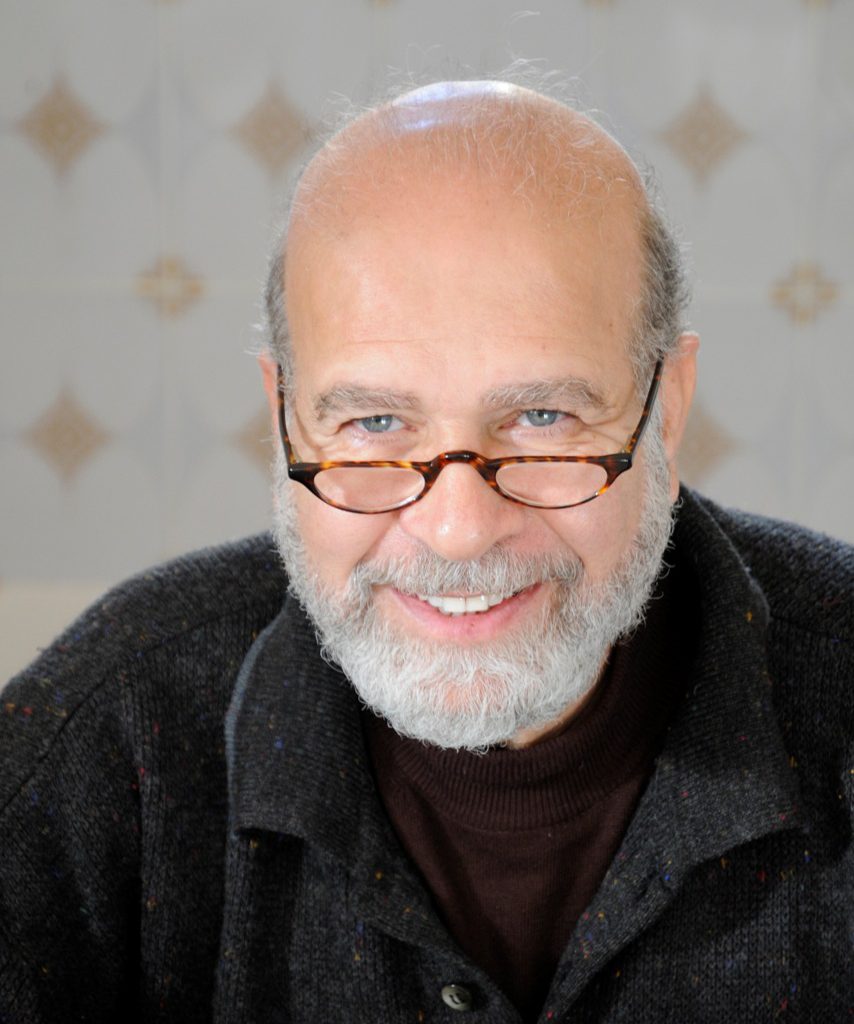

Algerian artist Rachid Koraïchi is known to work with a variety of materials and is characterized by having a collaborative spirit where he integrates local talent into his work that is exhibited globally. He comes from a background that is not only deeply immersed in local North African arts but also a Sufi tradition. (To view a cross-section of Koraïchi's work, click here)

Rachid Koraïchi, born in 1947 in Algeria, studied at the Institute of Fine Arts in Algeria before moving to Paris in 1971 where he also continued his studies in fine arts. He now lives and works between Tunisia and France where he has established studios in both countries.

Koraïchi recently won the 2011 Jameel Prize at the Victoria & Albert Museum for a selection of embroidered cloth banners from his series Les Maitres invisibles (The Invisible Masters).

Khaleejesque learned more about the significant artist, his thoughts on the Middle East and North African art world and what his plans are after winning the prestigious Jameel Art Prize. We probed his thinking on the rising importance of street art, the contextualization of his work and his plans for next year.

How has winning the 2011 Jameel Art Prize contributed to your sense of achievement?

Well, after the Jameel Prize ceremony in London, I went straight back to my studio in Tunis. I had already started a new series of paintings that needed to be finished in time for the forthcoming Art Fairs in Abu Dhabi and Dubai. From mid-October, I travel to the Algerian region of the Sahara where I’ll be developing the work of creating a major date-palm plantation – a project that is both ecological and devoted to the cultural sustainability of the region. I consider this project to be a non-ephemeral form of Land Art.

From the 14th of January, 2012, there will be the opening, at the Institut du Monde Arabe, in Paris, of an exhibition devoted to the Tunisian Revolution, in which one of my works – an immense embroidered triptych covering 36 square meters – is included. This is my contribution, and also a means of paying my respects to the tenacity of the Tunisian people, since I too suffered major problems at the hands of the Tunisian Ministry of Home Affairs and the various courts during the rule of the dictator. I’ve decided to pour the Jameel Prize prize-money into financing other projects that I’ve been planning, particularly one that will centre on India and possibly Nepal. It seems to me to be only right that the money I receive from such a prize should go back to support the work of skilled craftsmen even as it allows me to create an entirely new piece of work for exhibition.

What are the most important things to keep in mind when appreciating your work? How do you contextualize it culturally?

As regards to my work, I would say that even though I’ve been living and working in Paris for the last forty years or so, I’ve always insisted on maintaining strong links to my North African roots at the same time as fully participating in the world in which I live. I have always wanted people to see and appreciate my work in a universal manner. By this, I mean the understanding of my work in terms of the symbols, signs, marks – even vibrations – which have always been the common language of mankind and of which many examples remain in the cave paintings and rock art that is our shared inheritance since the dawn of time. Such art is not difficult to read since the underlying language is easily decipherable to all. We read this ‘writing’ in the same way that the men and women who weave carpets read their symbols, or again, like tattoos, or the signs traced on pottery, all of which tell us so much about other civilizations. I add some of my own offerings to the crucible of signs that already exist, in the hope of enlarging, in some small way, the great repertory of symbols present around the world.

How is your work in conversation, if at all, with contemporary Middle Eastern artists that explore street art?

Personally, I’ve always been involved, ever since my earliest days as an Arts student, with art in the streets: whether you’re talking about the creation of commissioned murals on the exterior walls of buildings or of more militant posters and flyers, quickly designed, printed and pasted up in public spaces in reaction to rapidly developing events. My work has always been there to support international Liberation movements: the struggle of the peoples of Vietnam, of Africa and of the Palestinian people, not to mention solidarity with immigrant workers or the victims of natural catastrophes.

To take this idea of Street Art a step further towards the realm of the plastic arts, I’d also want to mention my many large-scale installations and ‘interventions’, such as the light sculptures lining the riverside quays of Grenoble, similar light sculptures in road tunnels in the centre of Algiers and the banner-hangings around the façade of the Comédie Française in Paris.

Where do you go for inspiration?

I suppose that it’s both the current times and the unfolding events of the day which most structure my thinking, and whatever work I create grow out of that interactive and interrogative process of reflection. To realize my own works I’ve always felt the necessity of collaborating with other creative types – whether they be poets, musicians, writers, dancers or theatre people – with whom, for many years now I’ve enjoyed working to weave together multi-media projects. To cite just a few of the many authors and poets with whom I’ve been privileged to work and by whom been inspired: Michel Butor, Nancy Huston, Mahmoud Darwish, Mohamed Dib, René Char – the list just goes on!

– Plus Aziz

Image Credits: Top Image: Ferrante Ferranti – Middle Image: V&A Courtesy of October Gallery, photo by Jonathan Greet – Third Image: V&A Courtesy of Artist and October Gallery, photograph by Ferrante Ferranti