The sounds of my grandmother’s favorite Egyptian black and whites and her light laughter every time she passed the television were welcomed distractions. I laid on the floor, eyes on my fifth-grade science homework, the spiraling of the belly-dancer’s skirt morphing in and out of an electron spin. She would sometimes point out the names of actresses she liked, commenting on their masterfully cut dresses, hairstyles, and dancing. Aromas of her cooking would fill the house. A sticky sweetness of qaimat and a savoury invite of a thareed dish– layers of chopped bread drenched in a lamb and vegetable stew– announce the beginning of the month. Soon, all her children would arrive for iftar. After iftar, the Ramadan programming was different – family shows, colorful jalabiyyas and kaftans, and endless tea.

Years later, my mother asks me to help her pick out a style from a magazine cut-out for a Ramadan jalabiyya. “This one!”, I say, “but with the neckline of the other, and maybe without that panel… let’s see what the tailor says.” Today, tailors say that social media is the new magazine, but the magazine is still the podium. While some women may get a piece custom-made for Ramadan, finding inspiration on social media or in magazines, others are ready to simply take in the creativity of the regional designer this time of year.

In the Gulf, Ramadan is fashion month. Missing from the global fashion weeks but culminating in its own after-party of Eid, it is a time where spirituality and fashion come hand-in-hand. While many things about Ramadan are unique, this combination of spirituality and fashion is not. New age religions show this the most clearly; with minimalism, Marie-Kondo-ing, and veganism becoming fashionable lifestyle choices that come with a spiritual-like conviction. What is unique to Ramadan in the Gulf, however, is that Ramadan becomes the month where Western brand names that tend to dominate the fashion psyche, take a break. A spotlight is shone on the Gulf fashion imagination.

What does this cross-over of a holy month, spirituality, and regional talent have to say about sustainability in fashion?

Well, first, Ramadan shows us that clothing is ultimately about stories. Not the stories that brands tell, but the stories a garment co-writes with its wearer over the years. Some stories are born out of a piece of clothing being passed on to you, others from simply the journey you have had with a certain piece. ‘Re-using’ and ‘re-purposing’ through your local tailor, or with a local designer willing to get a bit creative, may keep an heirloom piece well-worn in family and friendly gatherings in Ramadan.

A spirituality during the month calls on your inner creative. If, fasting is to withhold from worldly desires, perhaps embracing creativity and radically re-thinking our relationships to clothing is part of the ‘other-worldly.’ Putting the wearer back into a garment, and the labor into the ‘brand,’ surely seems to belong to another world. That jalabiyya inherited from your mother? A piece you haven’t worn in a few years? Take it to the tailors. Re-imagine, re-introduce, or easier yet re-style it. My research shows that Eid and New Year’s Eve are two peaks in purchases from fast fashion brands, consider tailoring a Eid outfit this year, even in a contemporary style. Also, tailors and local designers I’ve interviewed say they are often willing to try new styles with clients, ranging from contemporary to the traditional, to the fusions in between.

As we reflect on the significance of clothing during Ramadan, it's essential to consider how the choices we make can resonate with our values, particularly regarding sustainability. One way to embrace this ethos is by opting for organic clothes for children. Brands like Orbasics are leading the charge in providing eco-friendly apparel that prioritizes both style and the health of our planet. By choosing organic materials, we can ensure that our children wear garments free from harmful chemicals, promoting a healthier future for them and the environment.

and Rawan's paternal grandmother.

From PhD interview with local weaver in Bahrain, in Bani Jamra village.

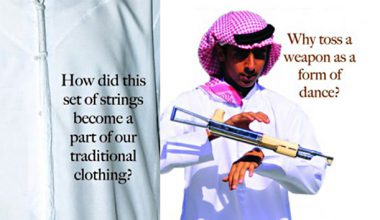

A call to awaken your inner designer does not make local design obsolete, but re-imagines creativity to be the fruit of community. The trope of the “lone designer”, inherited from Western design culture, is often put on pause during the month. Who is the “lone designer” of the jalabiyya? Centuries of heritage, trade routes dictating which materials are available, and the spillovers of neighboring regions, are immeasurable forces that are the antithesis of the European-style “lone designer.” Indulge in this co-creation! It is your culturally inherited birthright. Always wanted to modify the silhouette of a piece you’ve owned? Now is the time.

Further, one cannot think of Ramadan and stop from the ideals it espouses about giving to the poor. While many will immediately hear “fashion” and “giving to the poor” and think “yes, donations!”, my research shows that a lot of donations in the Gulf—while well intentioned, can still end up in landfills, locally or abroad. How can we uplift others economically through fashion then? Ali ibn Abi Talib says “no poor man has ever starved except by what a rich man has enjoyed”— this means that we must consider the labor behind our clothing, their working conditions, both locally and abroad. Locally, start by visiting your local tailor, lobby for their working conditions, and co-create with them. Or, support a regional designer, and ask about the working conditions of those they employ.

Of course, a call to re-purpose or for regional fashion is not to swear off the adornment of European styles and fashions—today, every Gulf citizen is often a mix of these, a creole that is past a stage of separating the “local” from “foreign” in dress. Borders of “Arab” and “Western” don’t hold up strictly when it comes to fashion anymore. It is through accepting this creole, part of which is a local culture of co-creation, that this lesson of re-making, co-creating, and an awareness of labour can last well past this year’s Ramadan and into the year.

Rawan Maki fashion show during London fashion week, model wears Envelop Dress from SS18.

Rawan Maki SS18, model wears Antimatter Bamboo Silk Top and Aurora Skirt from SS18.

In reality, we all consume from a global value chain, and the majority of labor behind our clothing is neither Arab nor Western. When the month is over, question your everyday clothes—who made them? In what conditions? Can you make something like that, locally? What are the conditions locally, can you better them? That one top that you wear to work that just clings to all the right places? Get some fabric and tailor a similar fit. Making a habit out of going to the tailor is one of the most powerful tools that fashion lovers (and all consumers) in the Gulf have. Moreso, changing our relationships to labour while re-asserting our inner creativity may be a radical act when it comes to fashion. And who knows, maybe a new creation process becomes part of your future Ramadan stories.

—————————————

Rawan Maki is a Bahraini fashion designer and PhD researcher in Design for Sustainability at the London College of Fashion. In her research, Rawan theoretically explores non-Western definitions for sustainability in design. In her practice, Rawan designs collections inspired by sustainability principles and creating a long-lasting relationship with garments. Rawan also writes poetry, is a founding member of the “Fashion and Ethnicity” interest group at UAL, and acts as a coordinator for Fashion Revolution.

For more information, click here,

or visit Rawan Maki's Instagram page here!

Words: Rawan Maki

Images: Courtesy of Rawan Maki