Mohamad Hafez, Syrian architect and activist-artist

Disgruntled with the regime, in February of 2011, fifteen young school boys from the Syrian city of Dar‘a were arrested for spray-painting on school property the resounding and uproarious Arab Spring slogan: A-sha‘ab yurid isqat-a-nidham (the people demand the downfall of the regime). Any attempts that called for their release were ineffective. Thusly, in March of 2011, protests escalated marking the start of the still ongoing Syrian uprising. The civil war has since resulted in the global displacement of Syrians seeking asylum abroad.1 From this expanding diaspora, a community of Syrian migrant and refugee artists are actively responding to the egregious crimes and antipathy of war with the depth and empathy instilled in their work.

While his migrant’s journey may differ from those who fled the war, of these activist-artists is Damascus-born architect, Mohamad Hafez. Presently based in New Haven, Connecticut (USA), Hafez is recognized for what he terms as, “sculpture portraits,” miniature life-like models of Syrian urban-scapes—from the privatized interiors of homes to the exteriors of old Damascene neighborhoods. Hafez’s sculptures developed alongside the civil war. And while they mark the intrusion of war, his models equally impart elaborate Syrian memories of home-life before the crisis through the deftness of his architectural skills. His artworks have been exhibited on internationally renowned platforms, and he has since been recognized as a 2018 Yale University Silliman College Fellow.

From his hotel room, not far from Cornell University where his latest exhibition is taking place, Hafez answers my questions on art, the potency of nostalgia, Old Damascus, and the refugee crisis.

Beginnings

Malak Al-Suwaihel: The year is 1984. You were born in Damascus, Syria. However, shortly thereafter, your family moved to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia when you were barely a month old. What was the impetus behind such a protracted move from home with an infant in tow?

Mohamad Hafez: Before I was born, my father, a retired surgeon, studied then lived in Germany with my family. At the time, in the late 1970s, there was a wave of nationalistic movements burgeoning amongst the Arab diaspora community. Impassioned and enthused by the ethos of these movements, my father was eager to return to the Arab world to serve his native land. And so they packed their bags and returned to Damascus. Unfortunately, in the early 1980s, it was a tumultuous time in Syrian politics—there were bombing attacks and other weaponized transgressions.

He realized at this point that moving back wasn’t the right decision. From there, he began looking for employment elsewhere. And that’s when, after I was born, we moved to Medina, Saudi Arabia. After a year or two, my father then received the opportunity to work at a military hospital, which had two divisions, one in Riyadh and the other at Al Kharj (South of Riyadh). My father was the head of surgery at Al Kharj.

M.S.: You lived in the Kingdom for about 15 years in a compound designated for British, American, and Arab doctors of varied nationalities. You have expressed that you did not socialize with Saudis and other residents, nor did you experience life in Saudi Arabia outside the compound much. What was that period of your life like? Did it aggravate feelings of alienation or the feeling of being contained? And where was Syria on your mind during this time?

M.H.: The compound that we lived in at Al Kharj was your average doctor’s residence. In the 80s and 90s, Al Kharj was a small and simple town, and so was its schooling sector. My father wanted a better education for my siblings and I, so for that reason, we commuted on a bus for an hour and a half every day from Al Kharj to a private school in Riyadh. We’d wake up at the crack of dawn and be home well after my parents had lunch. It truly tested my endurance and was a lesson in patience that paid off. We received a great education. However, my seclusion wasn’t due to systemic reasons. We simply did not have much time left to socialize.

Also, the compound was enormous, and housed around 200 families—so there was no shortage of friends. In that way, the compound acted like a bubble. I did not, by any measurement, harbor aggravated feelings of alienation. I know that on paper it seems like I was trapped within a compound that shielded me from locals. Contrary to that, I have very pleasant memories of growing up in Saudi—it was tranquil, safe, and happy. Actually, in school (Riyadh), I did have friends from Saudi families, and they were equally dear to me. And of course, my perception and experience is only mine and does not discount the experiences of those who felt alienated there.

At the time, Syria was not on the map for me, so to speak. We used to go to Syria during our summer vacation to visit family and friends back home in Damascus. Really, as a young boy I had yet to develop and understand deeper concepts and nationalistic feelings about culture, historical roots, and the homeland. A young child takes everything for granted. In terms of identity, who I am is half “Khaleeji,” (from the Arab Gulf), because of the sentimental memories I hold of Saudi throughout the 1990s.

M.S.: How would you then describe your early years? I don’t mean to linearize, flatten, or to diminish from your lived-experience, but where would you place your youthful years on the two extremes of angst or infantilized bliss?

M.H.: Life has changed for children nowadays. I don’t mean to belittle anyone’s experience, but from what I see now as an adult, life today is rife with politicized conflict. In addition, the millennial experience of life has been forced to speed-up to reflect the advancement of the internet. What has suffered as a result of that is kids now barely play outdoors, they barely get creative, so they barely make trouble.

I thank God I had the opportunity as a child (I’m from the last generation before the millennials) to use the extent of my imagination to entertain myself. We build forts, rode bikes, played football [soccer] under the rain, and molded shapes out of sand and mud. These childhood memories are rich with life-long lessons—I didn’t have a cellphone in hand to distract me from experiencing my surroundings. In fact, I bought my first cellphone in university, and TV time was limited to an hour or two a day. I do miss this time. As for anxiety, that is an emotion that persists throughout any childhood, and usually centers around the child’s future and the unknown.

Adolescence, Identity, and the Return to Old Damascus

M.S.: The year is 1999. Upon your return to Damascus, you describe your homecoming as a time of rediscovery—an exploration of your roots, who you are, and where you came from. Can you please recount these initial memories of return—both narratively and emotionally as a young boy?

M.H.: Going back to Damascus at the age of fifteen marked the first time in my life when I was consciously searching for an identity—who I am, my sense of belonging, my familial roots, and what it means to be a Damashqi (one from Damascus). My initial memory of return, is of my first trip to Old Damascus. I remember walking with my family and being in awe of the aging buildings—the Umayyad mosque, the Roman structures, the old churches and mosques, the streets, the crowded shop fronts, and the busy cafés.

This visual experience was one that I had never had before. I would describe it as a ‘celebration of life,’ and the near harmonious cohabitation of a multitude of races and religions in one space. From its structural beauty, I developed a love for Damascus’s diverse social fabric. And, as a budding architect, what heightened my attachment to the city were the centuries old structures of churches alongside mosques, which meant that the concept of tolerance existed well before these aging buildings. I understand that my words about peace and coexistence sound hackneyed or commonplace, but present generations are more familiar with the politicized reality of war, sectarianism, tribalism, and blatant racism that persists in Syria and Lebanon. For the generation that might not remember a time before the current Syrian Crisis, how do you convince them that there is a history that precedes this time of violent divisions?

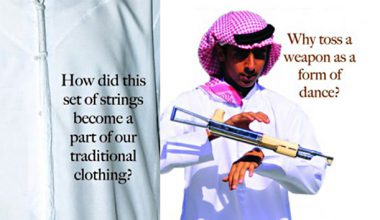

My enduring wish is that we can reawaken these sentiments of understanding. It is this notion of sympathy that informs my artwork—a precedent of hope that platforms the push for development in the near future. The role of Arab art at this time is to reacquaint present generations with their historical context. If we lose the knowledge of our history as Arabs, and succumb to the media’s sensationalized depiction of Arab and Muslim culture as exclusively violent, then so will our artistic expressions be erased by such generalizations. I tell my peers here in America, artists are documenters of their time, so their work should reflect their present condition. There’s nothing wrong with painting passive flowers, but that’s not my place in history. Hundreds of artists will paint flowers, but how many Arab and Muslim artists will make it his life’s work to bridge the gap of commonality and communication between the West and the East at a time of heightened animosity and xenophobia. There are a handful of us [Arab artists] that are living in the West, therefore it becomes our duty and responsibility to ensure the production of such timely and meaningful art.

Education, Career…America

M.S.: You have mentioned in numerous publications that your family has faced what you describe as a “forced migration” that took place three separate times throughout your life. Without confusing the journey of the migrant and the refugee, but consciously taking into consideration the current dismal circumstances of the Syrian refugee crisis, can you briefly take us through your (migratory) journey?

M.H.: In regards to ‘forced migration,’ I experienced it when I first traveled to the States to study architecture. I was first admitted to a university in Damascus, but I was not accepted to their architecture department like I had initially planned—despite having a high grade point average (GPA). Long story short, after four years of living in Syria, I found myself at Iowa State University with a single-entry visa. And with the concurrent events of 9/11, it was especially difficult for any individual from an Arab and Muslim country to enter and leave the United States with ease due to heightened surveillance. For that reason, the safest option was to refrain myself from travelling out of the US. I didn’t see my family for the next eight years. What this ‘forced residency’ generated in me was an intense longing for my homeland. My love for Syria grew, and I regret not acquainting myself with it better—especially those spaces that are now obliterated by the war.

Whatever the case may be, when someone leaves a country or region they are particularly fond of, a sense of nostalgia begins to develop. This nostalgia is the connective tissue that informs my artistic work. ‘Nostalgia,’ in my perspective as an architect and artist, is connected to and associated with the sense or feeling of a place. For that reason, my work can be appreciated by a wider audience that isn’t necessarily Arab or Syrian. The reason for that is, my work pulls at the strings of our collective human understanding of longing for a particular time and place—a homeland. This nostalgic element in my work is also found in Germanic, European, and global expressions of a life in diaspora. That solidarity comes from our shared human experience of exodus or leaving our homeland for the pursuit of a better life elsewhere. No one makes that decision lightly.

Because my family and I are safe, I recognize that I am blessed. Therefore, I, as a Muslim, Arab, Syrian architect and artist living in diaspora, have this responsibility to voice and direct international attention to those who were incapable of escaping war. In my opinion, to have escaped is a privilege that comes with a major responsibility: for an artist to use their platform and access to a Western audience to amplify the voices of those who are struggling.

M.S.: The year is 2003. So you moved from Syria to pursue your studies in the US. From there, you moved to and currently reside in New Haven, Connecticut to further your career in architecture. What did it feel like when you were disconnected and sent back in a diaspora again? And why New Haven?

M.H.: There really is no solid reason for moving to New Haven. It’s a beautiful place that’s conveniently situated between Boston and New York. So it’s very accessible, and near the shore. The reason I work in New Haven is because I’ve been hired by Pickard Chilton [architectural firm]. The firm’s partners also went to Iowa State like I did, and have been fundamental in supporting my artistic endeavours for the past 10 years. I am truly honored to be working at such a supportive firm. In addition, I think it’s very important to be in proximity of and to establish an amicable relationship with a number of prominent universities and colleges. Because I find my work to be more educational than to be the fodder of commercial art galleries, I find that a space that encourages further dialogue like a higher educational institution is a better fit.

Artwork—Ode to Syria

M.S.: You are both a practicing and accomplished artist and architect. Can you talk to us more about how these two fields and identifications coalesce and overlap, in your experience? Your deft architectural skills are present when you create your life-like miniature sculptures, so do you consider yourself an interdisciplinary artist?

M.H.: From my understanding, people can’t just be one thing. Unfortunately, the most glaring problem I find in our educational systems today is that it prepares students for a single profession, skill, and line of work—for instance, you study medicine, therefore you’re just a doctor. However, in the past, people equipped themselves for more than one title, or set of skills. A visual artist was also a scientist, doctor, astrologer, and poet [“Renaissance man”]. It’s human nature to be enthusiastic and curious about everything! In my case, my profession as an architect and my practiced skill as an artist do not clash; the two practices are mutually beneficial.

My artworks [miniature urban-scapes] have clearly benefited from my skills as an architect. As humans, we are complex. This complexity in our being cannot be diluted to a single craft or profession. Similarly, we cannot be diluted to a single culture or nationality—to just a US passport, a Syrian passport, or a Kuwaiti passport, etc. When an artist reflects this multilayered nature of being human, they begin to build on a lot of common denominators between themselves and those on a global scale. This is how we draw similarities and rid ourselves of tribalist divisions.

M.S.: In previous media outlets, you have made the following statement: “If I can’t go home, I will recreate home.” The statement is true of your art form, a series of sculpture-portraits of Syrian visual vignettes—from domestic quarters to the exteriors of neighborhoods. And while your art has developed alongside the civil war, you also choose to elaborate on Syrian memories of home-life before the crisis. Can you tell us more about your art?

M.H.: In regards to my dual professions, the more contemplative question to ask is, ‘how does art influence architecture?’ What I have discovered through my interactions with refugee families and those that have been forced to abandon their homelands is that people share and maintain an intimate bond with their homes and its architectural essence. This love for one’s native architecture can be specific to the windows or balcony of a remembered building, where said individual might have leaned out of, while listening to Fairuz [legendary and influential Lebanese singer], and enjoying the night breeze. With that in mind, as an architect, I take into consideration these intimate moments, so my projects go beyond the efficient practicalities of architectural design. To create more unforgettable memories for a child, a window must be very deep to allow the child enough space to safely look out. It is in these moments that an architect becomes an artist—when they are crafting memories. That’s why I stress on the multi-media aspect in my work—the smell of the bukhoor [incense], the sounds of the mosque’s call to player, etc.

M.S.: The year is 2011; and you are finally able to return to Syria after living in the States for an extensive period of time. Accompanying some of your exhibited sculpture portraits are sound bites and recordings of your time walking through Damascus’s streets in early 2011. Can you talk to us about these recorded “moments,” and what do they mean to you now after the commencement of the civil war in later 2011?

M.H.: The recordings are of life back home, and come from my intense longing for home. After the eight years I spent in the US after 9/11, I had the chance to visit Syria. It happened through a work project [with Pickard Chilton] that was being implemented in Beirut, Lebanon. For a trip that should’ve taken a week, I ended up staying in Syria for over a month while waiting for my visa to be renewed by the embassy. Regardless of the wait, this visit was one of the most memorable times of my life. It was the start of 2011 [before the civil war], and because I so intensely missed Damascus, I walked around the streets recording the day-to-day activity.

When you place these recorded sounds against my sculpture portraits, they add a different dimension—one that brings these miniature representations alive. The sounds of people’s voices in particular triggers your imagination and transports you to their world. When the call to prayer meets your ears as you visually take in a life-like miniature structure of a remembered Damascus street, it’s difficult not to immerse yourself in an art piece that utilizes the auditory. There’s so much you can relate to when you view my work, you don’t necessarily have to be Syrian. The common denominators are present in my art pieces—we all share a personal relationship and reference point to certain memories of chirping birds, children playing in the neighborhood, music and conversation from cafés, or calls emitting from places of worship.

Art, Civil War, and the Refugee Crisis

M.S.: Can you elaborate on the shift of your artistic expression of Syria from one of nostalgia to one that seeks to make visible the turmoil, deterioration, and forced migration experienced by Syrians dealing with the outstanding tragedy of the war? Your expressive and poignant series, Unpacked: Refugee Baggage, delves into what you call “emotional baggage” and is a tangible display of the humanity that is so woefully erased by war. What do you hope to achieve through your efforts?

M.H.: This series visually relays the story of ten refugee families from Sudan, Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, and Syria. Sculpted out of their own suitcases, I attempted to visually represent these families’ memories of home and their journeys as refugees. My reason for such a wide-ranging project is to respond to the discriminatory image framing the ‘refugee.’ My artwork points at the fact that the refugee crisis is a global problem. It has affected people from all over the world who have fled their homes due to war, economic strife, climate change, and more. So to paint the issue with one broad stroke is simply unjust. My aim is to humanize the ‘refugee,’ by way of collecting the stories of refugee families through sit-down interviews. From these conversations, we extracted a 90-second sound bite, which is the average attention span, to supplement each suitcase. Also on display is a placard that briefs the reader on the particular family’s journey and what they are doing now in their new place of residency. Many are working, others pursuing their education—and none, as the prevailing rhetoric narrates, are taking advantage of any nation-wide system without contributing to the social and economic fabric of their host country. This rhetoric of refugees as invading populations that take jobs from nationals is false. I have no patience for it, and it must be countered with activism and art.

M.S.: Correct me if I may have misconstrued your explanation of the following:

During an interview with NPR, you mentioned that those Syrians who left at the start of the civil war in 2011 were able to do so because they were financially capable and could afford to flee (this is your own experienced observation).Can you please elaborate on that? And, building on that observation, if I may ask, where do you position your family?

Follow-up: How would you describe the difference between a ‘refugee’ and ‘migrant’—politically entrenched terms that are unfortunately confused as synonymous.

M.H.: At the start of the uprising and commencing war in 2011, the crisis wasn’t at the violent height or escalation as it became in its later stages. So back then, for those who had familial connections to people abroad, it was easy to leave. That’s what I meant during my NPR interview. As for the difference between a refugee and a migrant: politically speaking, I identify as an immigrant, as I came here [to the US] on a student visa, I was then employed with a working visa, and then a green card. As for the ‘refugee’ identity, they are an individual that forcibly leaves their homeland to escape persecution or oppression and are compelled to enter another country to find safety and stability. This difference that you bring up in regards to the ‘refugee’ and the ‘migrant’ touches on a bigger body of work that I have yet to complete. So, hopefully, if we talk again in the future, I can have a more relevant answer for you.

Recognition

M.S.: Your accolades are innumerable. Well deserved! What is your most admired achievement?

M.H.: As I’ve mentioned, I do not care for these accolades. By that I mean, they don’t affect my desire to produce artistic works. In fact, I hate the spotlight! Because I initially came to be known from dire circumstances [the ongoing Syrian Civil War], for that reason, to be recognized is a bittersweet feeling. By the same token, I am blessed to be recognized and for the platforms that have propelled my work. But all in all, I see my work as a duty and a responsibility to do good with my platform. It is not a vanity fair, and I could care less about the spotlight.

Art as Therapy

M.S.: Would you say that what you create artistically is therapeutic for you—helps you come to terms with the ongoing Syrian crisis? And is that a deliberate objective of yours for those perceiving your artwork?

M.H.: My work is indeed therapeutic. At the end of it, my work is for me alone. I am blessed to have an audience and people that read my work. But I craft my models and artwork, first and foremost, to heal myself. I strive to live a life that’s worth living and sets me apart from what others are doing. How do you live a life worth living, you might ask, with everything that’s going on in the world today? First, one must know when and how to erect a figurative partition and a solitary space for themselves, their thoughts, their particular expression. My retreat of solitude is my studio. I find a sense of therapy in the time spent making my miniature sculptures. When I look back at these detailed items that I have created after five to six months of work, I can barely remember 50 percent of the process. This means that, when I am making art, I am in a trance-like state, and I have entered an almost unconscious, soothing imaginative space.

Note

- Abboud, Samer Nassif. Syria: Hotspots in Global Politics. Polity P, 2016.

A version of this article was featured in Khaleejesque’s September 2019 issue.

Words: Malak Al-Suwaihel

Images: Mohamad Hafez

mohamadhafez.com