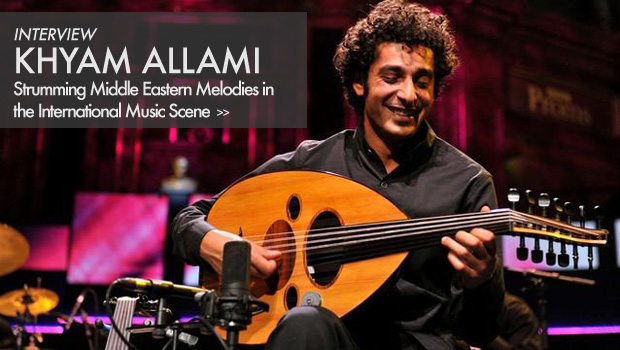

When it comes to Middle Eastern musicians, Khyam Allami stands out in his extensive collaborations, studies, and prolific activity. As ironic as it may sound, he created a name for himself in the West by playing ethnic and Middle Eastern music and strumming beautiful tunes using the Oud (the Middle Eastern version of the guitar).

Some of Khyam's most recent projects include a beautiful Oud-based concept album titled Resonance/Dissonance and he also drums for Knifeworld a progressive-rock band.

Khaleejesque caught up with Khyam to talk about the music industry, his love for the Oud, how he’s developed himself as a successful musician, and his future projects.

What’s your take on the music industry?

I think the music industry is a crippled dinosaur and the sooner artists become more independent and rid themselves of this stifling beast the better.

How does the Middle East’s music industry differ from that of the West?

A big question with a long and complicated answer.

The Middle East music industry is almost totally different to the West and has a big problem. There are only corporate commercial labels and distribution and commercial pop music is almost the only thing pumped into people's brains (see Rotana and Melody). Fortunately, there are some people trying to make a difference, such as Forward Music in Beirut, Lebanon and the regional based Eka3 who I’m working with in the Arab world, but it’s a long and winding road. Incognito is another label, which made huge in roads but unfortunately went bust and its efforts left unrecognized.

Music in the Arab world is a deep social phenomenon. It is an intrinsic part of daily life for most of the population and it is loved. But for this wonderful reason, the culture of going out and buying albums doesn’t really exist in the same way as it does in the West. Even the concept of “albums” doesn’t really exist. What does exist is a culture of songs which were once long musical works, like Um Kulthum in the 60s and 70s for example, but are now radio-friendly pop numbers which are downloaded onto mobile phones, viewed as video clips on TV or listened to on YouTube.

Music in the Arab world is a deep social phenomenon. It is an intrinsic part of daily life for most of the population and it is loved. But for this wonderful reason, the culture of going out and buying albums doesn’t really exist in the same way as it does in the West. Even the concept of “albums” doesn’t really exist. What does exist is a culture of songs which were once long musical works, like Um Kulthum in the 60s and 70s for example, but are now radio-friendly pop numbers which are downloaded onto mobile phones, viewed as video clips on TV or listened to on YouTube.

At the same time, people love to experience music live, but because most of the population is living on breadlines, concerts need to be very cheap, if not free, to have a good attendance. Unless they are big commercial artists like Nancy Ajram or George Wassouf, obviously.

Add to that the struggle against a mass-consumer based pop music monopoly supported by top commercial brands (Pepsi, Vodafone etc..), legal complications and restrictions on distribution which are different in each country, lack of venues and music retail shops, a low level of international musical culture due to the lack of music available, and it all makes things very difficult for the independent artists of today to make any money at all, and therefore develop or nurture their art to a reasonable international level. (I also wrote an article about this topic for UK magazine Index on Censorship.)

How did you get into Oud and what do you think makes this instrument special?

The Oud is an enchanting instrument and I was led to it by various different desires and for various reasons. At the time, in 2004, I was going through a particular low point in my life in which many questions required answers and many dreams begged for realization. One of those dreams was to stop being a “jack of all trades and master of none”, another was the continuous overwhelming desire to dedicate to music and nothing else.

At the same time I was reading a lot about music and mysticism (in particular the work of Joscelyn Godwin) and had an incredible hunger for knowledge and desperation for learning, study and research. I also wanted to re-balance myself and my lack of contact with Iraq and the Arab world, the Arabic language, Middle Eastern culture and music in particular.

The Oud was the perfect instrument. It is the instrument of choice for composers, theorists and philosophers; it has an ancient history and fascinating contemporary developments in its performance techniques. And the development of solo Oud playing by the Iraqi school of Oud players has enriched its mystical and meditative qualities which re-affirm the healing effects attributed to it by 10th century philosophers such as Al-Farabi and the Brethren of Purity. It is truly a magical instrument.

Tell us about your training in Egypt, Turkey and the UK. How did various maestros take your skills and understanding of Oud to the next level?

Tell us about your training in Egypt, Turkey and the UK. How did various maestros take your skills and understanding of Oud to the next level?

Most of my studies where with Ehsan Emam, a master of the Iraqi school of Oud playing who lives in London. I learnt so much from him, both musical and extra musical that I cannot even begin to recount his immense influence on me. It would take a book, or two.

My studies with Naseer Shamma, Hazem Shaheen and Mehmet Bitmez were all very short but extremely influential, which is why I mention my studies with them. I learnt a lot of technique from them which helped me jump light years ahead of where I was when I went to see them. Their work also opened my “ears” to new ways of playing the Oud and a different kind of sensitivity to the sound and power of the instrument.

With masters like them, you can have a 20-minute lesson and then spend one year if not more, trying to play what they tried to teach you in those 20 minutes.

How has social media enriched your engagement with your audiences?

In one way, yes, and in others, no. Obviously I am able to interact with far many more people across the world very quickly and easily, but that interaction is very superficial most of the time as I really can’t spend all my hours on Facebook and Twitter communicating with people. I feel like enough of an administrator as it is!

Regardless of that, it is a great thing and I love being in touch with so many people, but it will never replace actually talking to people at concerts and interacting with audiences in the physical realm.

Many around the world classify your style of music as ‘World Music’. How does this label sit with you?

My quick-fire response: we all like to complain about genres and labels and definitions but at the end of the day, we need them in order to be able to find things. The label “world music” irritates me because of its Anglo-centric view point, but it was created for the British/American music industry so you can see why.

I studied with and know some of the people who were at the infamous meeting in London where that label was decided upon so I have a reasonable insight. But if I was there I would have definitely voted for “International” as a category. “World” is really divisive… it's as if there’s the UK/USA and the rest of the world: “us” and “them”. I don’t agree with generalizing and don’t like to do it, but sometimes there is a lot of truth in stereotypes too.

So in a way, the choice of “World Music” does reflect an element of how those countries view themselves culturally with regards to the rest of the world.

Explain the concept behind your new album Resonance/Dissonance.

To be honest I don’t like to talk about what’s behind the album very literally, but Resonance/Dissonance is a very subtle and honest reflection of a personal journey, which in itself reflects a greater more universal process. It is an attempt to render various points of that journey in music.

To be honest I don’t like to talk about what’s behind the album very literally, but Resonance/Dissonance is a very subtle and honest reflection of a personal journey, which in itself reflects a greater more universal process. It is an attempt to render various points of that journey in music.

In terms of the tracks, Individuation represents a personal awakening and desire to take a certain road or path, through its ups and downs; Naghmat Tahrir is a dedication to the Iraqi artist Tahrir as-Samawi (RIP). Tawazon I: Balance, An Alif/An Apex, Tawazon II: or lack of, The Descent, and then Reverie, a final long repeated fade out which represents the never ending nature of the process, the lack of clear definable answers, the need for dreams, and the importance of hope.

It makes more sense when you listen to it.

Tell us about some of your latest collaborations with other musicians and what’s next.

This year I’ve had the chance to work with many great musicians. Most recently I played Electric Bass with Egyptian singer Maryam Saleh at a concert at El-Geneina Theater in Cairo which featured new arrangements for her songs by Tamer Abu Ghazaleh.

I am currently working on putting together a new group called The Alif Ensemble as part of my residency here in Cario. It will feature a number of musicians including the fantastic Egyptian electronic musician Maurice Louca. We will hopefully launch the ensemble in the Middle East and go on tour in December.

I’m also working on composing the music for a new Royal Shakespeare Company production of the theatre play Marat/Sade by Peter Weiss, directed by Anthony Nielson. It will run from October to November in Stratford-Upon-Avon in the UK.

Before that in September I will be going on tour in Ireland with the group Zahr, founded by Italian pianist Francesco Turrisi and featuring my dear friend the Italian percussionist Andrea Piccioni and Italian singer Lucilla Galleazzi.

And next year in April I have a big project and UK tour planned in double-duo with Andrea Piccioni on percussion, plus Palestinian Oud player Ahmad Al-Khatib and percussionist Yousef Hbeich who will release their album "Sabil" on Institute du Monde Arab very soon.

For more great Middle Eastern musicians check out the websites of Eka3, Forward Music and Incognito, listen to Kamilya Jubran, Bridge and Psalms by Khaled Jubran and you can listen to Khyam playing drums in Knifeworld.

– Plus Aziz

Photo credits to Hydar Dewachi