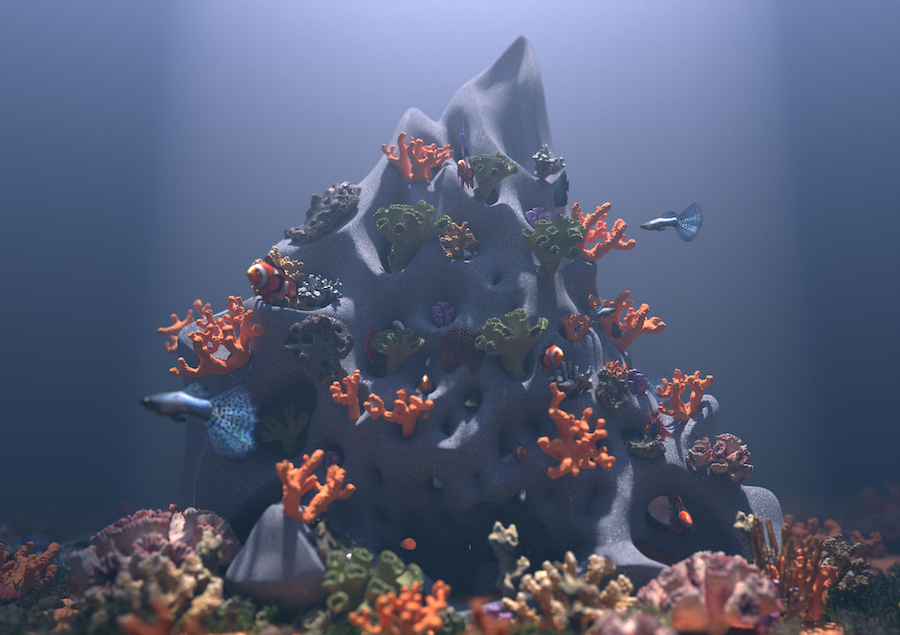

Dubai Institute of Design and Innovation (DIDI)’s May 2023 graduate exhibition explores the many disciplines of design, from product to fashion and gaming, with a special focus on sustainability ahead of the upcoming 2023 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 28). From multifunctional clothing created from zero-waste pattern-cutting techniques to underwater sculptures made from bivalve seashells to support marine life, the projects demonstrate the school’s approach to creative, data- and innovation-driven solutions that enrich communities and the environment.

DIDI, which offers the region’s first bachelor of design degree and a curriculum developed in collaboration with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Parsons School of Design, was established in 2018 to empower a new generation of designers, innovators, and entrepreneurs in the Middle East and beyond. The Graduate Exhibition is a key fixture in the annual calendar when senior-year students showcase four years of design thinking and product development.

Khaleejesque spoke with DIDI alumni, Dalal Jaber, to know more about the process behind her final project.

Saira Malik: Can you talk a little bit about your final graduation project?

Dalal Jaber: Shell Waste is a project that aims to explore seashell waste as a sustainable biomaterial. The project sheds light on applying the material in marine environments to support preserving aquatic wildlife colonization while raising awareness of the rising issue of shell waste in the country.

(S.M.): What was the inspiration and idea behind the project?

(D.J.): The idea began with my admiration of the ocean and marine life. From a very young age, I was fascinated by seashells and started collecting them from the sea to save as souvenirs. I began experimenting with them and adding them to my projects in college. For my final project at the Dubai Institute of Design and Innovation, I decided to push the boundaries and see how far I could go with seashells to make a true impact. I began researching the origin of seashells, where I discovered the rising problem of coral bleaching, providing me with a gap to intervene and make an impact.

(S.M.): How did you approach researching this project?

(D.J.): This project covered three research methodologies. First, a collaboration with marine biologist Dr. Barbara Lang-lenton. Her invaluable insights were crucial in the material development and shape design stages. The second methodology was lab experimentation. This step mainly consisted of trial and error using different natural binders that mix with seashells.

The third was secondary research, which included gathering data and information on seashell waste and other existing and potential applications of it in the market.

(S.M.): What was the biggest challenge when designing the project?

(D.J.): The most difficult challenge was finding the right binders to mix with seashells. Considering the project is meant to be underwater, it made selecting the binders that much harder. Grinding and dehydrating the shells was also difficult because the machinery it required was not available at my disposal.

(S.M.): What were your main findings after completing the project?

(D.J.): Using seashells as a biomaterial has significant potential not just in the marine environment but also on land. Since the launch of my research, there has been growing interest in different sectors to pursue this project further and I am thrilled to do so. I recommend reevaluating how we treat waste to see if we can reuse elements for good – that’s the mindset we should have.