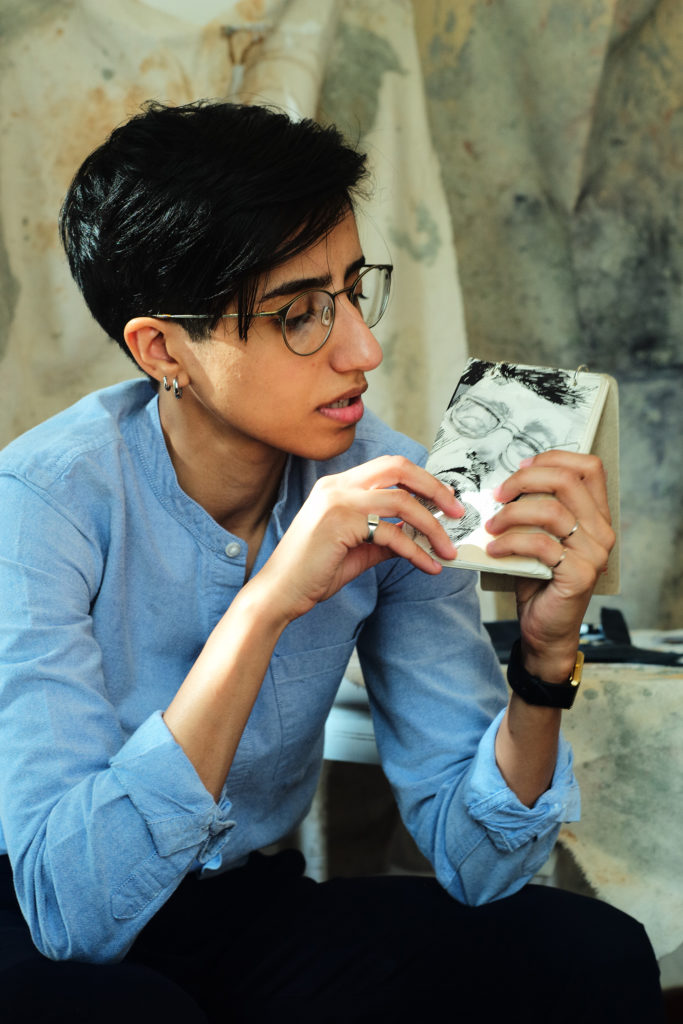

Words: Dana Aljouder

Images: Aziz Al-Motawa & Zahra Al-Mahdi

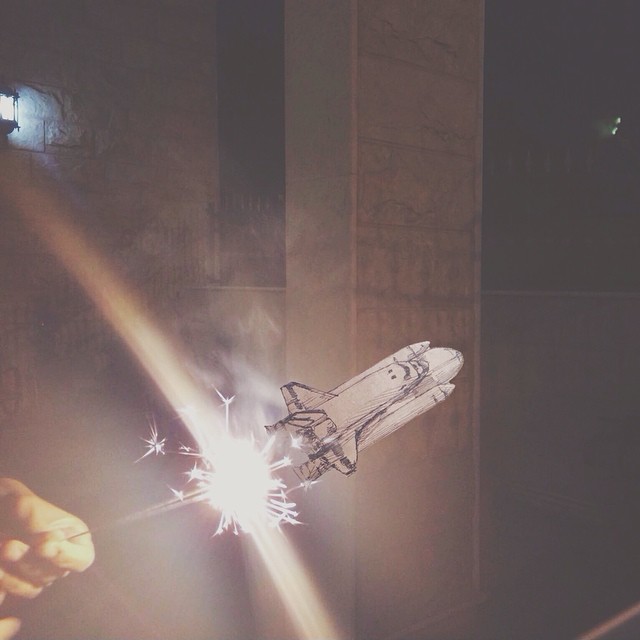

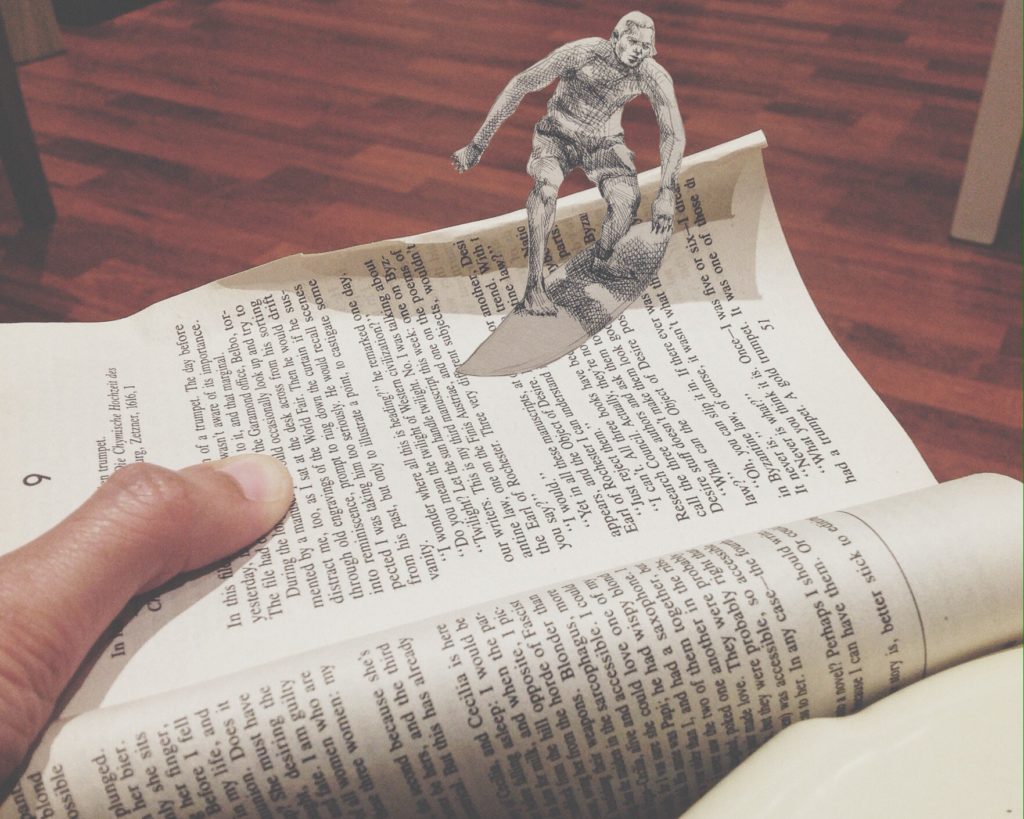

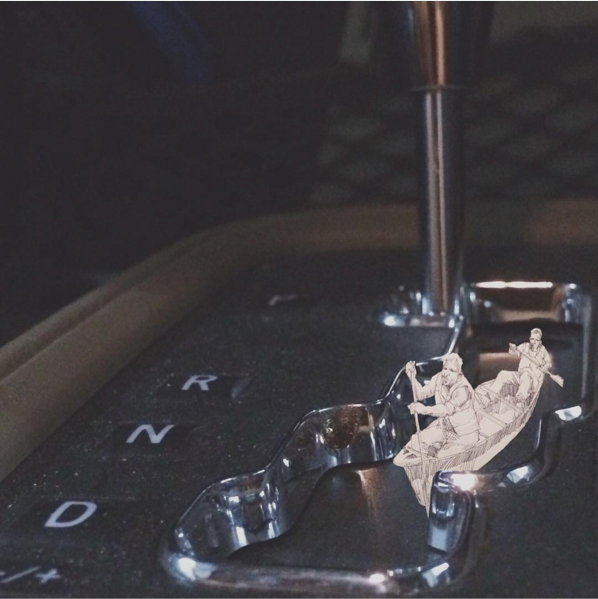

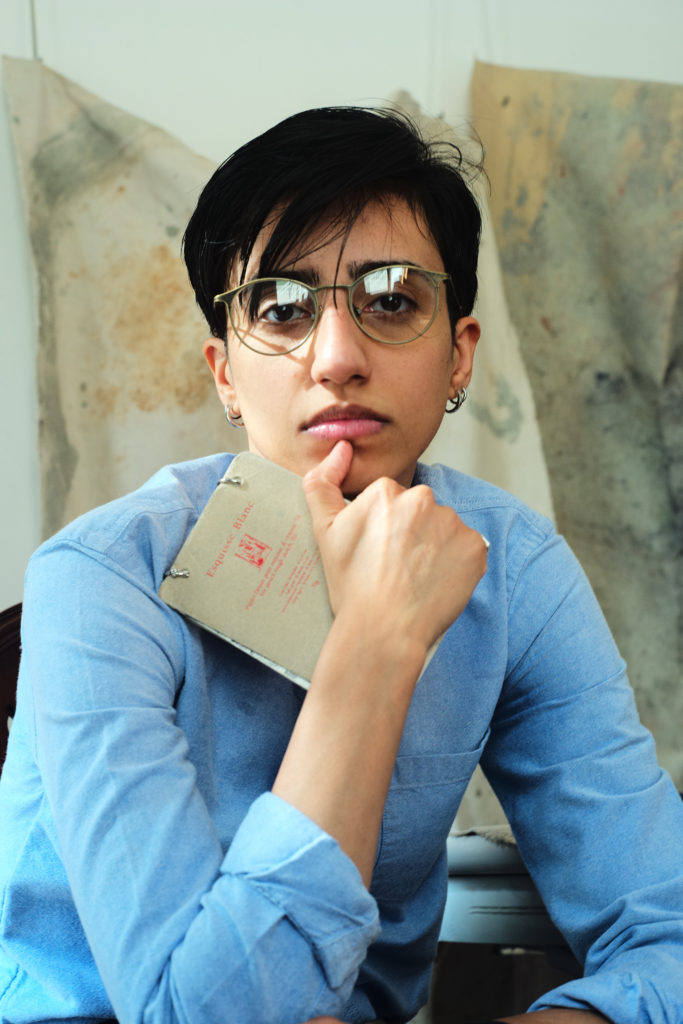

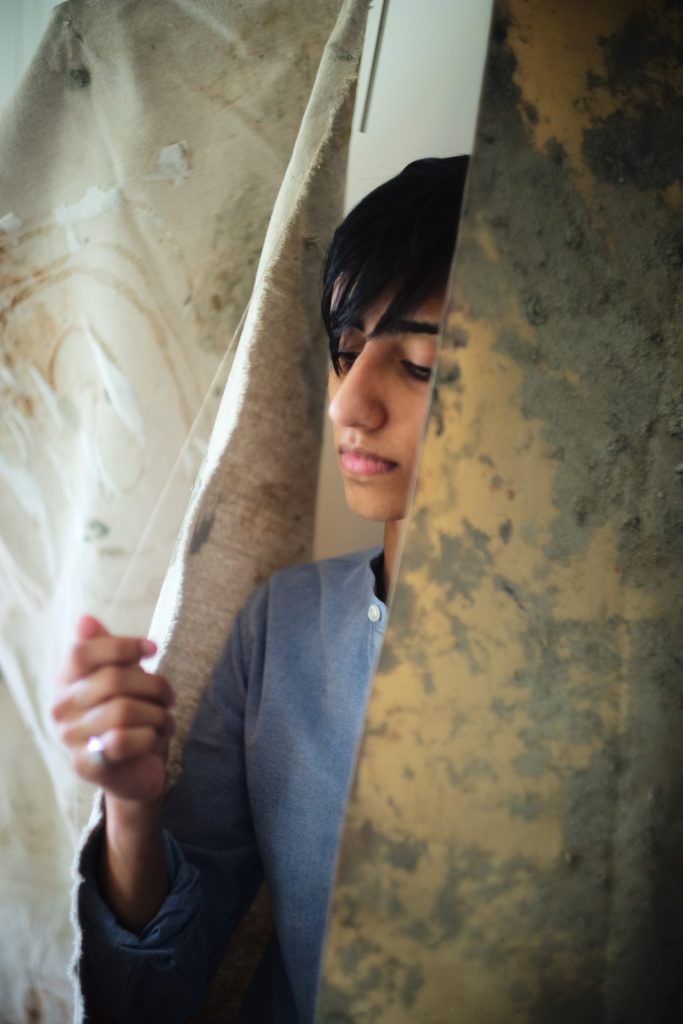

Zahra (Zouz) Al-Mahdi, otherwise known as Zouz the Bird on social media, is a Kuwaiti artist, writer, and filmmaker who stays relevant by constantly evolving through a number of artistic mediums—from collage work, ink sketches layered over photographs, installations of dissected anatomical figures, and animation on live action. She challenges herself, all while tempting her audience through various genres—from science-fiction to the post-modern decline—and through the frameworks of the post-colonial and post-structural lens.

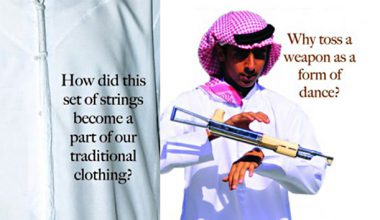

She’s an artist whose playground is the city in which we live in — and us — her characters. In her ‘mockumentray’ mini-series, Bird Watch, Zahra examines mundane and common interest topics from a marginalized, alienated perspective to reveal hidden truths about health, the myth of origins, gender, and the business of philanthropy. In an impromptu mini series on social media called Haltoomat (grievances or complaints), she pulls the veil off of society — a sheer and transparent fabric, she argues, that we’ve already pulled off ourselves.

Zahra has tried her hand in publishing, debuting her graphic novel We, the Borrowed in 2016, and has collaborated with award-winning Kuwaiti author Bothayna Al-Essa on a children’s book for adults, Half Hearted City (مدينة بنصف قلب), in 2019. In film, she has participated in the Imagine Science film festival (both in Abu Dhabi in 2017 and in New York in 2019) that brings together the sciences and humanities through filmmaking. And in 2015, she was part of the La Femis, Gulf Summer University in Paris, France — an intense 5-week scholarship program on cinema and filmmaking. In the Summer of 2018, Zahra completed a 4-week artist residency at the Blitz Valletta, an independent non-profit contemporary art space located in a repurposed townhouse in Malta that concluded with her 2-day exhibition titled, ‘Yardsticks: Subjective Tools of Measurement.’

Recently, she was nominated and accepted to join the 2020 fellowship program to be the first Kuwaiti TED fellow (not to be confused with TEDx). Due to circumstances related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the notable TED conference moved online, and Zahra’s talk was released on May 24, 2021 and can be viewed on TED’s website, here:

Her extrospection turns inward when she discreetly reveals that her grievances are indeed equally self-criticism rather than solely a societal critique. The truth behind her lens is refreshing while our screens serve us with a mirage of delusions.

On Current Affairs

Dana Aljouder (DJ): Do humans have a greater purpose on this planet or are we doomed from the minute we’re born?

Zahra Al-Mahdi (ZM): I talk about this a lot. Stand-up comedy is a big deal for me. So, there’s a George Carlin joke—he talks about how it's presumptuous of people to say that we’re here to save the planet. Because the planet has been through much worse shit than a discarded plastic bag, he says if we go extinct the planet will find a way to incorporate plastic into its system. So the planet is fine, we’re the ones that are fucked, and maybe the reason for our existence is that the planet needed plastic and just didn’t know how to make it. So he’s like, you wanna know what the higher purpose for humans is? Plastic! (laughter) The purpose for existence for us is—we’re almost done with our job is what I’m trying to say.

DJ: I’m told to ask you about your daily grind, but are you ready for the beginning of the demise of this physical world?

ZM: So ready. I don’t believe in the separation of the physical and the spiritual. They are one. I don’t like it when people ask me if I’m spiritual because that question doesn’t make sense. You are who you are down to the cellular level. So of course that is your spirit. Because people talk about body and mind as separate, but if you change one thing in your hormones, your personality will change. That’s your mind, it’s who you are and how you behave. That is your soul. That is your essence. So why is there a difference between my spirit and my leg?

DJ: I love your answers because it completely knocked off the rest of my questions like a domino effect.

ZM: Let’s go. Let’s do this.

DJ: What does this physical world look like to you?

ZM: Everything is physical. Even if we’re going to talk about material, as in materiality—there is nothing in this world that isn’t material—including religion. There is no religion in the world that is not physical. When you pray you need a prayer rug or prayer beads. Our body is physical, our brain is physical, and your tools of measurement (our eyes, our hands), they’re all physical. This is how we identify the world around us. For instance, I’ll boil it down to people saying, “I don’t appreciate artists who take money for their work.” But money is value. So if you don’t give art money, it means you don’t value art. It’s as simple as that. Let’s not f*** around. You want people to work for free, that’s what you want. Everything has its cost.

DJ: You must have suffered a lot with that.

ZM: Everyone does. What I suffered with honestly is the concept of advertisement — that the ad is materialistic and art is raqi (elegant, sophisticated). But have you entered the world of galleries and seen how an artist has to brand themselves before they do their work? All of that is an advertisement. I dress the way I dress for a certain reason, I’m branding myself, because otherwise people aren’t going to give a shit about my work.

DJ: I read somewhere that a high percentage of artists are picked up by galleries for the way they look.

ZM: Yeah. And I’m not offended if someone likes me or is attracted to my work because of the way I look. We are animals at the end and that’s the first thing we see. And I do judge people by the way they look because getting dressed is a certain choice. You know? So the world is material.

DJ: What would you say is an ideal world for Zahra?

ZM: An ideal world—it’s very difficult and sometimes I say things and then I realize maybe it's not such a good idea. But I’d like there to be a certain feeling of justice, where you get as much as you work for. I think that’s the part that bothers me the most. I know a lot of people that hustle and get close to nothing. And I know a lot of people that do nothing and coast, which is also a skill. But that’s what justice feels like to me. You get as much as you work for.

DJ: Why do you think that certain people have to suffer sometimes more than others in certain aspects of their lives?

ZM: I can’t for the life of me figure that out. And it’s mostly because of the chip on my shoulder.

DJ: What do you mean the chip on your shoulder? The privilege that we’re born with as Kuwaitis?

ZM: The only way out is through, but some people’s ‘throughs’ are much thicker than others, which means some people suffer more. And in our [Kuwaiti] society, privilege is such a wide term, you can’t really see who's suffering more than others. I once knew someone in high school who was an amazing artist but she was forbidden to paint at home because her family believed it was haram (a sin). It’s their belief, and art is taken away from her, and that makes her suffer. [Meanwhile], some people have the tools and the freedoms, but they genuinely are not interested in doing anything. And others have all the talent and I want to see their work out in the world, but they can’t—they’re hindered by their ‘throughs.’

DJ: Those are great. (pointing to polaroid photographs and dried flowers) Do you feel that documenting is a big part of your artistic process?

ZM: It’s a big part of how I think. I call myself an artist, writer, filmmaker, because it’s the form my work usually ends up in. But I see myself as someone who notices patterns, shows how things look alike, how ironic things are, so I’m more of an ‘idea person.’ When I write things down, I remember them better. Especially if they’re handwritten. Going back to them, I can see them in hindsight, and that’s how I form my ideas. So archiving, writing memories down, that’s the raw form of the result.

DJ: So some people feel like they’re married to one medium and I feel like that’s a disaster for the artist. Why do that when you could tell the story in so many different ways?

ZM: If you’re an artist, and if you’re into visual form, you can do a lot of things. You can learn how to make something and then you can make it. But I think that’s where the problem with the blank page—the writer’s block, creativity block—comes from. How do you start with the form? How do you start with the canvas? Why don’t you start with an idea, or a feeling, or a thought, or a connection? And then you transform it into anything else. But if you start with staring at a canvas, then you’re limited. So even with writers, why don’t you start with research? Making notes, or a joke, or something. Why do you start with a keyboard and an empty document? There’s nothing scarier than an empty page. Of course it’s scary, you have nothing. Why are you here? You went to an exam without studying? It makes no sense. So for me, everything I do, everything I think about, is something that I’ve seen, it’s a conversation that I’ve had that sparked something. Research. Everything is research.

75% of profits from the merchandise sold after the release of this episode were donated to Yemen through ICRC

The Cadaver

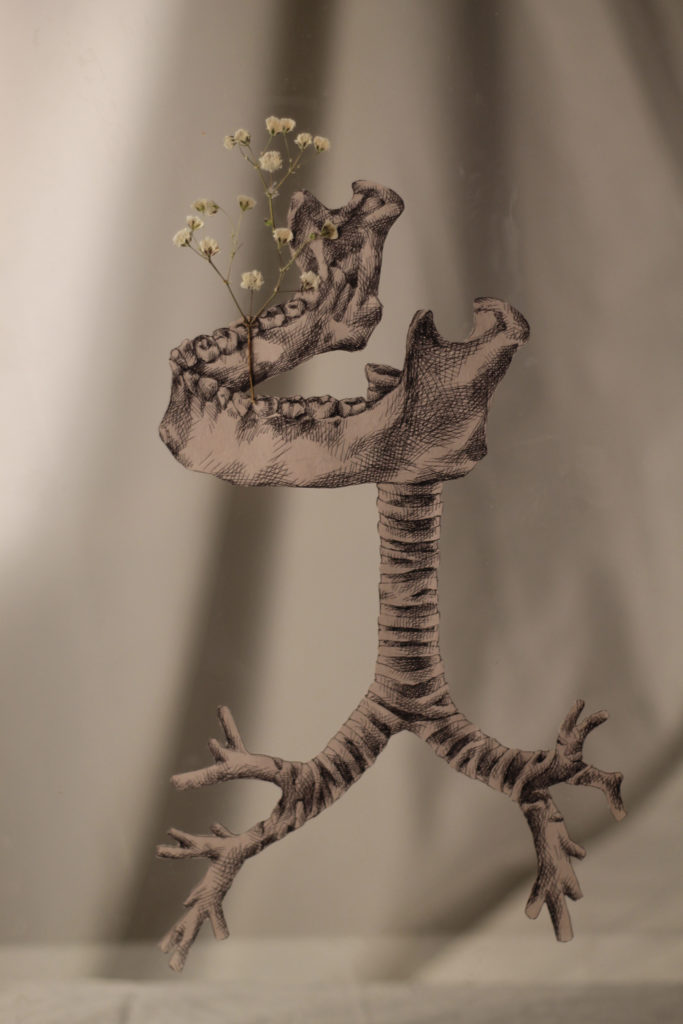

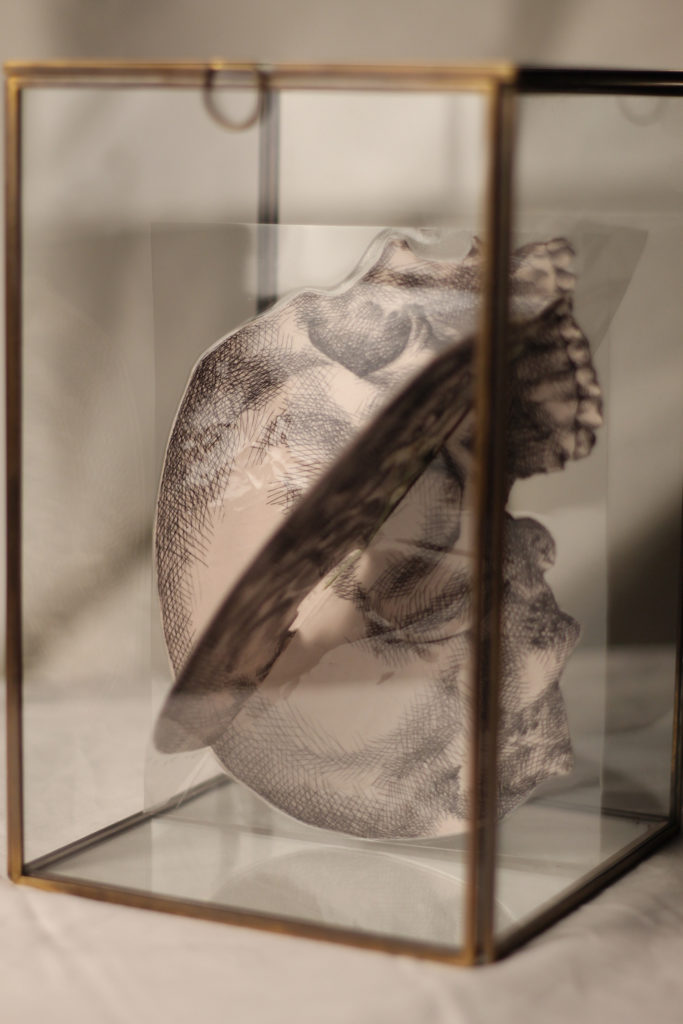

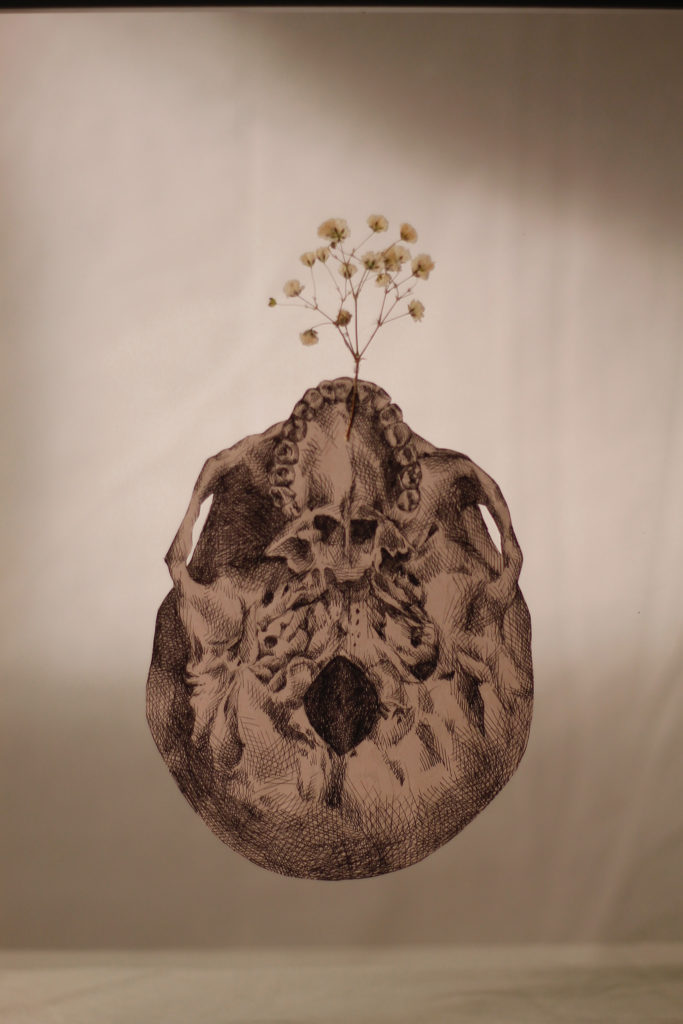

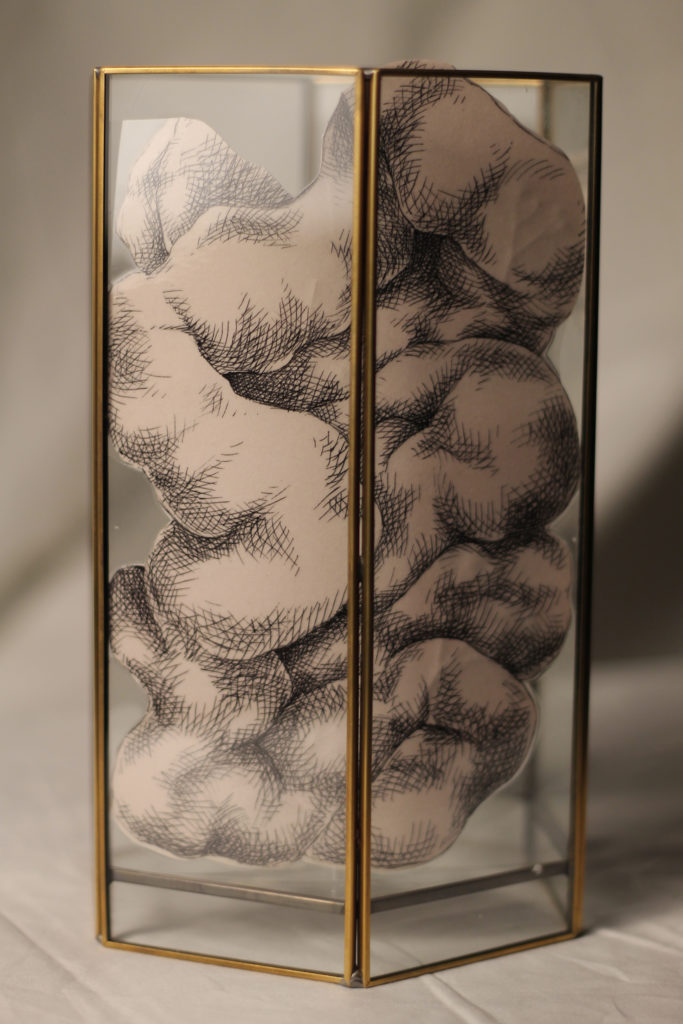

DJ: I want to know more about your attraction to drawing birds, cross-sections of the human body, and scientific dissection: cutting the paper with an exacto knife, and then placing the drawing in a container like a specimen—when does science start to become art?

ZM: I’m not going to get all philosophical in general and say that everything is a performance but —

DJ: But it is! And she is going to get all philosophical. It’s become ritualistic to you. Where did that ritual come from?

ZM: Specifically, drawing hands and birds started because I couldn’t. It was the most difficult thing for me to draw. And I do a lot of things because I can’t. It took me a really long time to be able to draw a perfect hand. It’s about how good the shading is. If I show you the actual hands, the fingers are too long for the palms—it’s anatomically incorrect. But it’s about how you work with patterns and how you use the pen and then it becomes muscle memory. With birds, it's the same thing because when you draw feathers there’s a pattern. Also, my handle [@zouzthebird] started as a joke—I really don’t like birds. And now I realize it’s more of a Batman thing. You know? I am what I fear.

That aside, about the cadaver, I was always fascinated with the way people reacted to the human body because people think that everything is a sum of its parts. The first time I saw that was in the National Science Museum—in a room of preserved specimens and deformed body parts. It was art and we’re supposed to be there for science. And ever since, I wanted to do something like that. So the first time I did it was in Dar Al Funoon [contemporary art gallery in Kuwait, est. 1994]. Shahad Bishara [Kuwaiti curator, designer, and founder of Visual Therapy] was curating, and I hung these slides of a dissected human body. And what I did was designate one slide to a male form and one slide to female. They were cross hatched and people don’t really wanna look because it's an open body.

DJ: What did you learn from drawing that and then juxtaposing them against each other?

ZM: That it’s mistaken for one and the other. And I like it. Maybe because I have this extreme of androgyny that’s in everyone and I felt like I haven’t celebrated it as much as I should, so that was a part of it. Judith Butler [American philosopher]—a summary of what she says is, because gender is on a spectrum, you’re never at the extreme end of the spectrum. Everyone’s failing at their gender to someone else. Like some people, I’m extremely female, and to some people I’m very masculine.

Borrowed Language

DJ: Has art become a medium of self-revelation? How so?

ZM: Definitely. Because my art comes from ideas I recently read, implementing them shows me what I’ve understood and what I’ve taken from it. Just a simple thought of making a mistake is ok, and that it can be better. John Cleese [British actor and comedian] from Monty Python [British comedy troupe and television show, estb. 1969]—do you know that story about him writing a play? So he wrote a funny comedy and then he lost the manuscript. And it drove him absolutely crazy. After a while he tried to remember what he wrote and wrote it again. And when the older one turns up, the newer one is better.

So you edit things, subconsciously, especially if you’re constantly thinking about them. Having work that I have done again and made better, and mistakes I’ve embraced, it has made me someone who is not afraid as much.

DJ: From your Book, We, the Borrowed, who are the borrowed?

ZM: So I was young when I wrote that, it was idealistic… Foucalt [French philosopher] was a big deal in my life. And Donna Haraway [American philosopher]—in her book [A Cyborg Manifesto, 1985] the language isn’t ordinary. It’s either symbols, photos, or bilingual. We are the language that we speak. If you are bilingual then you not only speak, but think in different cultures [and have adapted and understand those cultures]. So when we use a language without really living it, without changing it, without morphing it, we are borrowing it. If we borrow our language, we ourselves are transitory in our existence. What does that say about me as a person? If I’m not native to English and it’s the most comfortable language for me to express myself in, what does that say about me? I’m a borrowed person.

DJ: So is the Arabic language, as we know it, oppressed?

ZM: With our rigidity. We are oppressing Arabic with our rigidity—with what and how it should be—and how static it should be. Because it’s a beautiful and rich language, it can grow in many multiple different facets. Because we want to preserve it, we’re not allowing it to be a language—to evolve.

DJ: We’re suffocating it?

ZM: Exactly. We’re complaining about it being a dying language when we are suffocating it. So it’s extremely ironic what we’re doing.

DJ: What has been the most difficult transition in your creative career thus far?

ZM: It’s happening now, which is transitioning into the world of entertainment. The fine arts scene is not as productive for me as it used to be. It doesn’t reach as far, it’s a one-sided, single track. Whereas entertainment can take on multiple facets and directions—it can be academic, it can be artsy, and it can dabble in comedy—so it has everything that I want. Switching to entertainment is a big deal for me. This is what I want to do.

The Social Specimen

DJ: Your drawings have a nostalgic calling for a simpler time.

ZM: I used to be an oil painter. But I needed tools that I could take with me everywhere, so inking works. It’s much better than pencil because cross hatching gives you an effect that you don’t find in regular shading. I would do it, if there was a digital alternative that would give me the same effect. But I haven’t found one yet or it hasn’t been developed. As good as Procreate is with their brushes it still doesn’t give me what ink and paper can give me. If I can animate a minute in less than a month, I would do it digitally. It’s not exactly about my attachment to the form, it’s my attachment to the result.

DJ: Are we guilty of romanticizing the past?

ZM: Oh. yeah definitely. This romanticizing the past is not about the past. It’s about rigidity towards change and it’s about fear. So it’s about the fear of the future that makes us look at the past and say ayam etaybeen (the good old days). It’s nothing to do with the past. It’s about being afraid of not being able to keep up.

DJ: Zouz as a reflection of your audience, you’ve managed to playfully experiment with your viewers on social media by making us aware of our own faults. How do you manage to do this without offending us?

ZM: Comedy! Make something funny, and it passes—especially in Kuwait. If there’s an idea that’s hard to digest, even if it’s taboo, make it funny. Kuwaitis will swallow it up. And that’s what I identify with: if you’re funny you’re ok in my game. It’s really difficult for someone to say that they’re wrong but if you can manage to make them laugh at themselves. A laugh can break someone serious and powerful more than a yawn would.

The Prescription

DJ: You’ve put a scientific and psychological lens on our society, what’s next for Zahra?

ZM: More scientific and psychological lenses. So I like to take something that looks simple and then dissect it through our collective psyche and what that says about us. For instance when we say the word hareem (etymologically, a demeaning term for ‘women’) and what that means instead of nisa’a (collective term for women). Why do we still use that word [hareem]? And when someone whose a self-declared feminist says that, and then mistreats her domestic worker, what does this say about how we look at things? Your flaws are always going to sneak up on you. And honestly, it starts with the things I notice myself doing because I’m never innocent of my haltooma [the issues that I complain about], which is why I’m Zouz the Bird. Because I don’t like birds, and I have to remind myself that I need to take a hint [I am the thing that I complain about].

DJ: Finally, congratulations on being the first Kuwaiti TED fellowship –

ZM: Thanks!

DJ: Could you tell us more about this program?

ZM: It’s unlike any program that I've been a part of. You’re part of a whole family for life. They’re very active, very inclusive, and they help you discover who you are, what your capabilities are. I got introduced to it through Alexi Gambi [founder of Imagine Science]. He’s an amazing scientist filmmaker that I met through the Imagine Science festival. I think it’s important to mention him and Talal Al Muhanna [Kuwaiti producer]. These are two people in my life who have recommended me to things that I never thought I’d be interested in or could do.

DJ: And then my last question, how do you hope to impact our society?

ZM: People aren’t gonna change. But everyone has the capability of having a good time. Even if you are serious and rigid, you can laugh at yourself from time to time. You can let your guard down. Sit with yourself in the bathroom and look at the mirror and laugh at what you just did. That’s it. Just don’t be too serious. That's all I want, nothing more.

www.zahra-almahdi.com/

www.instagram.com/zouzthebird

www.instagram.com/azizmotawa/