The State of Kuwait was founded in the 16th century, nearly four centuries ago. It has thrived over the years, thus becoming an important commercial intersection between the countries of the Arabian Peninsula and beyond. According to historians, the region where the present State of Kuwait lies has been a historical stop for many prehistoric civilizations—as is evidenced by the remnants of the Hellenistic and Greek civilizations. The region was also the scene of several battles and decisive events in Islamic and Arab history—from Ma’rakat that Al-Salasil (“Battle of Chains”), which took place in Kazima in northern Kuwait between Muslims and Persians, to the battle of Mount Wara during which blood was shed from the top of the mountain to the base of the valley. As Kuwait’s population increased, Kuwaitis began to work in trades like pearl diving, fishing, and shipbuilding. At some point, Kuwait was the major harbor for ships traveling from neighboring regions. According to historians, the Kuwaiti coast was a hub that was busy with fleets of ships from all over the world.

Thanks to that embracing commercial nature, Kuwait became both a crossing point and a place to settle in for many. This contributed to the demographic density and diversity in Kuwait, and to the mosaic of cultures and social references from within the small state. Some older areas became more established and well-known after the construction of Kuwait’s first wall, and more so with the expansion of the second wall, which indicated the small state’s initial and later geographic borders. Within these shifting boundaries, the history of Kuwait is replete with historical events that played a decisive role in the trajectory of the region, which makes the country a destination for many scholarly travelers and those interested in exploring it.

Despite the important geographic location of Kuwait and the curiosity and concern of its pioneering people and visitors, there are very few and limited sources and literature on the history of Kuwait’s architecture—particularly between the 1950s and earlier. This was the main issue that Dr. Abdulmuttalib Al-Ballam faced when he returned home to Kuwait after acquiring his Ph.D degree in the USA and was assigned the position of Professor of the History of Architecture in Kuwait. Dr. Abdulmutalib is one of the most distinguished Kuwaiti architects, and holds a Ph.D degree in Architecture and Computer Aided Design from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He graduated in 2004 and returned to Kuwait to teach architecture at KU. At the time, the Architecture Department (KU) was newly opened and lacked sources on the history of architecture in Kuwait. But that was a blessing in disguise. The lack of literature motivated him to look beyond those sources that were designated to the history of Kuwait. Al-Ballam researched through literary, geographic, and even sociological documents to develop a program for for his particular subject—the history of Kuwait’s architecture. In fact, this inspired him to harness his skills in designing virtual cities using computer technology to recreate a virtual life-like model of the Old City of Kuwait.

Because of his substantial work that is both timely and well-recognized, we approached Dr. Abdulmuttalib for an interview to discuss his efforts to virtually reconstruct the historical city of Kuwait, as well as the obstacles and successes he encountered in this tremendous journey.

Anfal Al-Mutairi: Tell us about yourself, your qualifications, and your professional beginnings and interests.

Dr. Abdulmuttalib Al-Ballam: My name is Dr. Abdulmuttalib Faisal Al-Ballam, I graduated in 1996 with a BA in Architecture from the University of Louisiana, after which I worked at SSH Architectural Consultancy. After some time, I received a scholarship from Kuwait University (KU) to pursue a Master’s and Ph.D degree in Architecture, particularly in computer aided design, in the United States of America. I am very interested in designing new architectural forms by using an array of geometric shapes and merging Arabic calligraphy fonts. In my opinion, any real industrial revolution in the country needs to start by its local, individual industrialists and craftspeople who design products as solutions for minor and daily problems.

A.M.: What about your childhood, your upbringing, your beginnings, and the events that shaped your future.

A.B.: I grew up in a big house with a big family that collectively shared an interest in the arts. My brother and cousin were very good at drawing and designing instruments, which motivated me to compete with them and to learn more. This is when I noticed that I too possessed a passion for the arts and design—particularly the kind of design concerned with ‘space saving,’ like figuring out the best use for corners. So, when I was 15, my father asked me to design his house. For me, this is what most evidently made me feel adept and skillful in my field. And thanks to the trust my father put in me, I felt more assured towards reaching my goal as a professional architect. Another reason behind my fondness for the art was garnered by on of my favorite TV programs as a child. The program was called, “The Little Artist," which was broadcast by Kuwait Television and hosted by Mohammed Sheikh Al Farsi who presented the artistic projects of kids—from their paintings, sculpted models, to other works of art. This is the kind of purposeful programming that I find is missing today.

A.M.: Why did you choose to pursue Architecture as a study, seeing as it was only recently introduced as a major in Kuwait University?

A.B.: The major was not available during my high school studies, nor was I fully familiar with architecture as an academic specialization. All I knew at the time was that I wanted to pursue any field that was somehow related to design. Initially, I aspired towards a civil engineering major, especially considering that I was top of my class in the subjects of Physics and Mathematics. I planned to regularly attend the classes in civil engineering at KU and also to be one of the Kuwaiti participants in the Physics Olympiad in Amsterdam in 1990. However, due to the sudden and brutal invasion launched by Iraq against Kuwait at the time, it was impossible for me to compete in Amsterdam or to even start my studies. But every dark cloud has its silver lining. Due to the damages caused in the aftermath of the invasion the Government of Kuwait decided to send a group of students, including myself, to study architecture in the United States of America for the particular purpose of reconstructing and rebuilding the worn out infrastructure of Kuwait University. As I practiced in this field, I found that this is the subject that I had always wanted to specialize in since my early childhood years.

A.M.: Did you face any challenges when you first arrived in the United States to study architecture?

A.B.: Of course! I came from a country where the common academic culture and educational teaching methods mainly depended on a student’s passive reception of information. But I was surprised to find that the American teaching methods called for approaches that demanded of the student to think outside the box. For instance, in my particular field of architecture, instructors asked of the students to break up the usual concepts of beauty, which are conventionally confined to consistency. Yet, unconventionally, beauty can be found in what is usually considered to be ugly and inconsistent. This helped me significantly change my way of thinking. From there, I embarked on a feverish journey to seek beauty in new forms. So, thanks to my inquisitive methods and distinctive projects, I graduated with distinction and at the top of my class—the department at UCLA also wanted to offer me teaching position!

A.M.: The idea of virtually rebuilding the old city of Kuwait was widely approved at all levels. What inspired you to turn this idea into reality? Tell us about it and about the challenges you have faced during your journey.

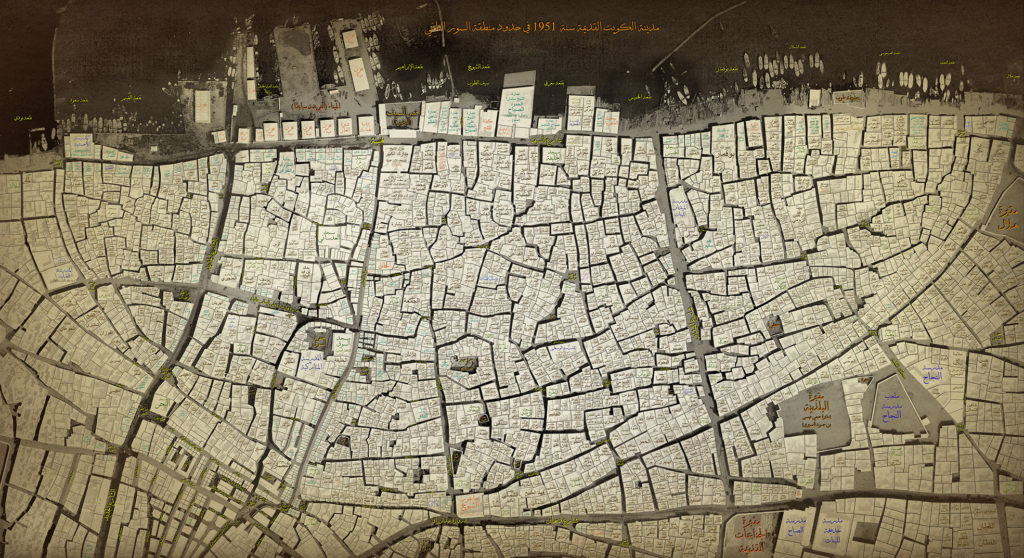

A.B.: The idea was born as I was conducting research into the history of architecture in Kuwait after I had returned from my doctorate trip. I was surprised to find that the sources are scarce and far in-between. The challenge was to reimplement the same methods I used as a student to think ‘outside the box.’ At that time, I found an aerial photograph of Kuwait that dated back to 1951. It was merely composed of lifeless blocks with little visible details. I compared it later on with the map drawn by researcher and historian, Mohamad AbdulHadi Jamal, and other maps by the historian, Zakariya Al Ansari. Then I managed to make measurements of the shades in that photo to calculate the dimensions and lengths of the buildings.

For a while, I lost interest in this whole ordeal, until I found paintings by a Kuwaiti artist, Ayoub Hussein Al Ayoub, that, in my opinion, are invaluable. Ayoub Hussein Al Ayoub was well-known in the 1950s for his folk art and paintings that reflect the daily life of the average Kuwaiti in the past. These paintings portray children playing traditional games, women on their way to the market, or men busy working at their trade. Al Ayoub’s paintings were full of life and teeming with details—most significant to my work were his artistic renderings of old Kuwait’s urban surroundings, which feature the structures of buildings, houses, and neighborhoods. After matching them, I discovered that the painted portrayals were in fact real places and structures that made up the old urban landscape of Kuwait. Apart from some minor errors in the paintings, such as lines corresponding to perspective, they were very meticulously portrayed, which greatly helped me identify the city’s features at the time.

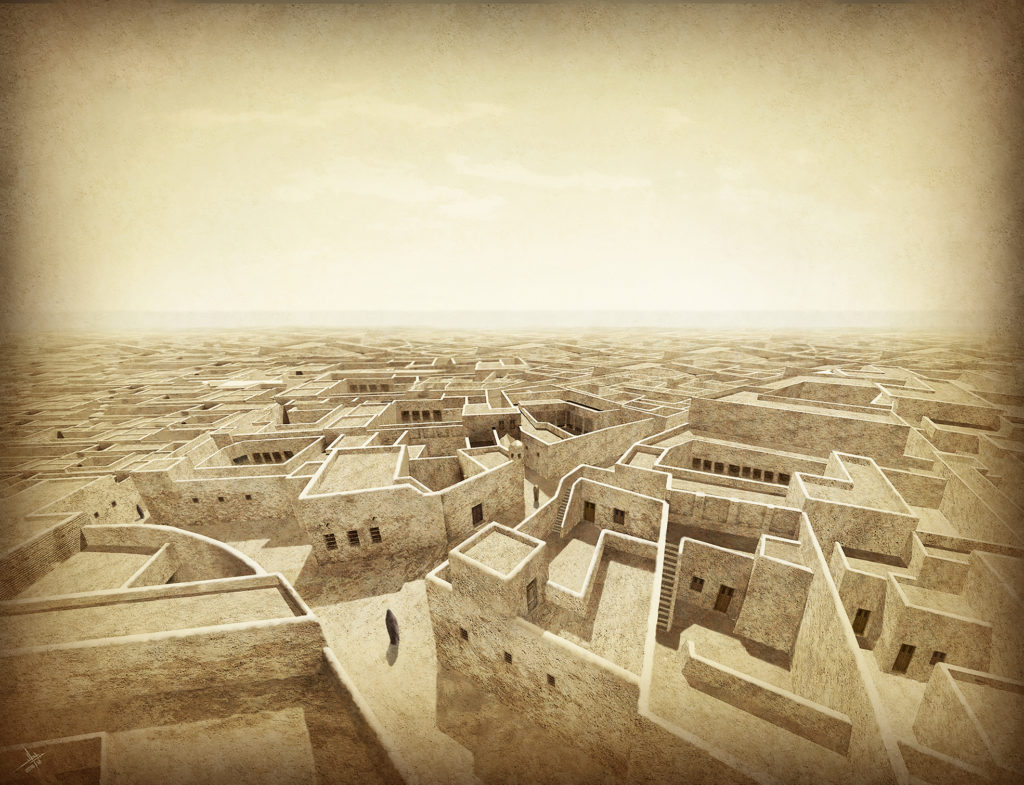

My next line of sources were non-local writings of Western explorers who navigated the old city. Moreover, we met some elderly Kuwaitis who were alive and witnessed that period of time. sadly, some of them died before they could be interviewed. However, we were able to gather enough information to start building the virtual city. The starting point was the Shuwaikh neighborhood and Al Khos neighborhood that were present when the first wall was constructed. Despite the apparent secrecy surrounding these initial areas, we successfully identified their overall structural features thanks to an aerial photograph. Then we moved to the second wall, which stretches from the Helal Fajhan Al Mutairi cemetery to the east, Saoud neighborhood to the west, and Darwaza Abdul Razzaq below. Thanks to the efforts of 100 volunteers and undergraduates and postgraduates studying architecture, we managed to virtually rebuild the city and walk through it with the aid of virtual glasses and other relevant technology. In fact, this is the only city in the Middle East that was radically rebuilt.

A.M.: What is the intended purpose of these efforts?

A.B.: It started as a personal initiative, but it soon turned into an obsession because I believe that the ongoing demolition of the old city is a heinous crime. Since then, no effort has been made to understand and document that old, diminishing city. This is why we have taken this issue upon ourselves at Kuwait University’s Architecture Department. With the aid of assistive technology, my main goal is to establish and create a significant and reliable resource—that builds on the modalities of traditional encyclopedic sources—to document the Old City of Kuwait for future generations.

A.M.: Do you have any plans to expand this project?

A.B: Definitely, we have already started doing so. We displayed the map in a shopping mall for the general public to see. Our new plans to expand the project include producing film documentaries about the old city of Kuwait. We will fly over the current cityscape and recall the historical events and everyday life that once took place at these locations. We also aim to create virtual museums and models of the city to expand on the current generation’s understanding of their history in order to instill in them a curiosity and concern for their ancestral past. In addition, we have already garnered interest from an investor to rebuild a part of the city in an existing location—project details that I, unfortunately, cannot disclose at the moment.

A.M.: What feedback did you get after the display of the map?

A.B.: The feedback was mostly positive. I saw people of all ages gathered around the map in an attempt to locate their ancestors. I also saw an old man crawling over the map with the help of his grandson to locate the family house. I also have a friend who felt discouraged and hopeless by the current socio-economic and political situation in Kuwait and found himself alienated and with no sense of belonging in his own country. However, when he saw the old house of his family marked on the map, he soon felt that he belonged again and started telling me about his and his family’s deep roots here in Kuwait, and how he overlooked them as he engaged in politics and other life stresses. No doubt, there were some prejudiced, narrowly nationalistic comments that denied the existence of some families and their origins, therefore rejecting the map as inaccurate. But thankfully, those comments were few. Our efforts to accurately locate the past residents of those houses scattered within and around the old city took a great deal of research, and diligent work.

A.M.: As this illuminating interview comes to a close, is there anything else you would like to share with us?

A.B: Yes. Remember that to make progress, we must first remember our roots. And the future is never complete, unless we come to terms with and recognize the past.

A version of this article was featured in Khaleejesque’s September 2019 issue.

Words: Anfal Al-Mutairi

English Translation: Malak Al-Suwaihel, Manar Darwiche

Images: ©Dr. Abdulmuttaleb Al-Ballam. Kuwait National Library®

2 comments

Comments are closed.