Combining architecture, furniture, and product design, interdisciplinary artist Majdulin Nasrallah’s work focuses on tackling notions of physical space in relation to the human experience and challenging political and social constructs. Holding a Master of Fine Arts in Design and a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Interior Design from Virginia Commonwealth University School of the Arts in Qatar (VCUarts Qatar), her work has been showcased in galleries from Qatar to Canada.

As one of the Artists In Residence for the Majaz group show at M7, her work “1948” depicts a subject close to her heart, the Nakba, when Palestinians were exiled from their homes.

We sat down with Majdulin to talk about her journey and evolving artistic practice where she uses her talent to weave a narrative of resilience and identity through storytelling.

Saira Malik (S.M.): How did you embark on this journey as an interdisciplinary designer and how has your heritage influenced your storytelling as a creative?

Majdulin Nasrallah (M.N.): Driven by my background in interior design, I became interested in the relationship between the built environment and the human experience, particularly the way in which space can be designed to influence human behaviour. During my two-years in the MFA program, I had the opportunity to explore this interest through more imaginative, rather than technical, ways. I began exploring the idea of “resistance” through storytelling, in the form of designed objects and experiences. Immersing myself in readings on spatial theory, I became intrigued by the politics of space, particularly the weaponization of spatial planning and infrastructure in Occupied Palestine. My MFA thesis explored spatial theories utilised by the Israeli military, but instead of perpetuating their tactics, I envisioned design as a force for both retaliation and restoration.

(S.M.): Can you tell us the story behind your latest exhibition “1948” and how you became a part of this group show Majaz at M7?

(M.N.): I was invited to participate in Majaz, an exhibition featuring works by 35 artists who took part in the Artist in Residence program at the Fire Station in the years 2015–2021. Each work acts as a metaphor (Majaz) for the artist’s journey and evolving artistic practice, capturing a moment or an idea that represents their experience during those years.

“1948” is the “Majaz” for the Palestinians’ right of return. When Palestinians were exiled in 1948 during the Nakba (the catastrophe), they took their house keys, hoping to return in a few days or weeks. Throughout 75 years of ongoing dispossession, Palestinians have carried scents of their land in their collective memory and consciousness.

(S.M.): What is the theme and subject of “1948” and what medium did you work with?

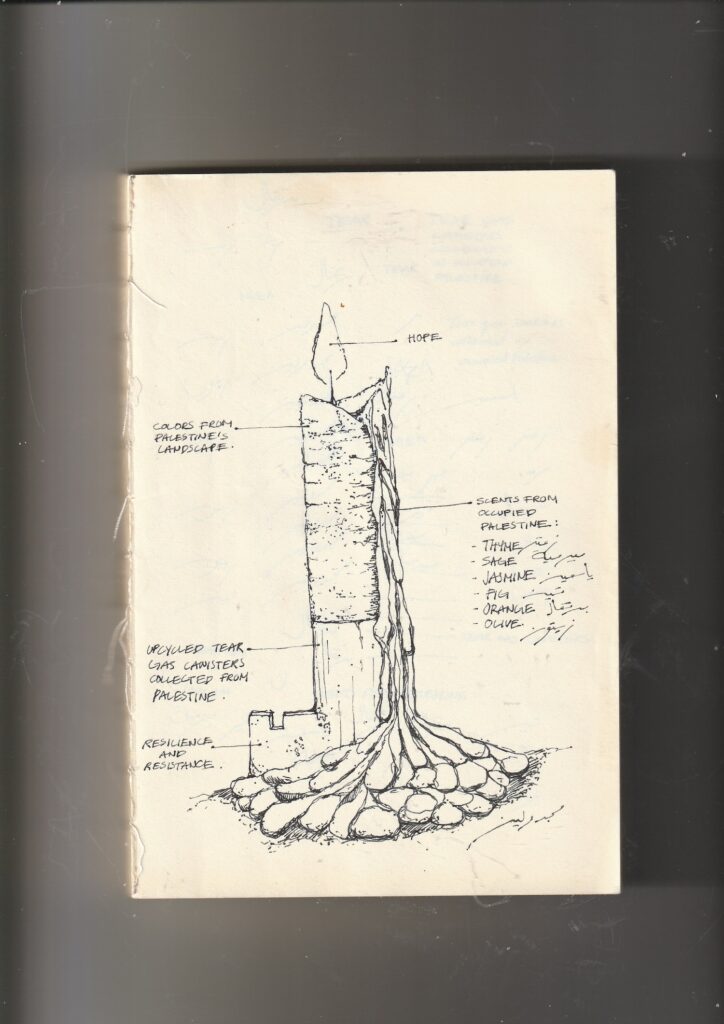

(M.N.): “1948” weaves a story of resilience, identity, and connection to the land. A series of six candles merge motifs of pain and hope, longing and resistance. They carry scents and colors from the Palestinian landscape and the diaspora, evoking memories and emotions associated with the homeland. Consumable and transient, the wax candles symbolize renewed hope.

The candle holder resembles the Palestinian key – a symbol of Palestinians’ right of return – and takes its material inspiration from the concrete of the demolished villages and houses. The scents in the “1948” collection are olive, thyme, sage, orange, fig, and jasmine.

The candle holder in the limited edition is made from upcycled tear gas canisters collected from the streets of Occupied Palestine, mainly the Aida refugee camp in Bethlehem, and Nablus. Its physical structure resembles the Palestinian key.

(S.M.): What was your creative process and how did you express the idea you had and evoke the concept that you wanted to materialize?

(M.N.): “1948” was initially materialized in 2017 during my first year in the MFA program at VCUarts Qatar, as part of a module within my Materials and Methods course. This module encouraged students to explore souvenirs as a means of representing their culture through designed objects that carry meaningful narratives, and to explore materiality and fabrication through mould-making and casting techniques. I chose to explore the Palestinian key due to its strong symbolism, reflecting both individual and collective Palestinian experiences.

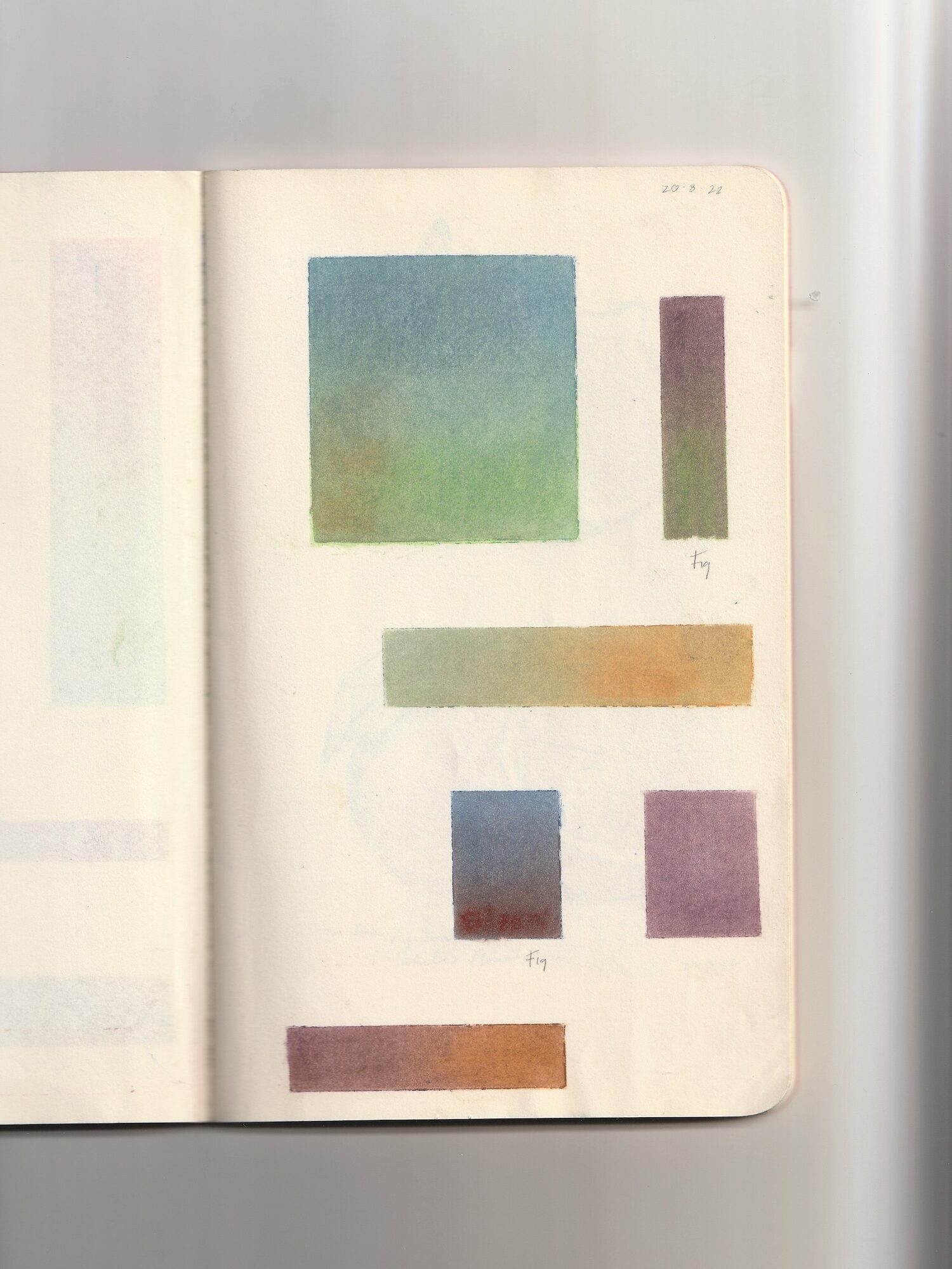

A few years later, I was invited by Yasmeen Suleiman, an educator and the head of the Materials Library at VCUarts Qatar, to further develop this project through the materials library postgraduate research program. Over the course of more than two years within the program, I worked on refining the design, experimenting with new materials, pigments, fragrances, and packaging options. “1948” is now available for sale at Studio 7 in Msheireb, Doha.

(S.M.): What importance did the raw material have in terms of having a strong message about identity and what were the challenges in sourcing it?

(M.N.): The choice of materials played a key role in defining the essence of "1948." Whether it's the symbolism embedded in the use of broken concrete, evoking the imagery of the demolished villages and homes, or the wax symbolising the resurgence of hope, each material was selected with deliberate intention. I find a poetic synergy in using contrasting mediums that harmonise in a hauntingly beautiful way, such as the juxtaposition of solid, cold concrete with the malleable, soft wax.

One of the most challenging materials to source was the metal of the actual tear gas canisters collected from Palestine. Collecting and transforming the canisters was a long and tiring process that took more than two years. Each canister had to be re-shaped and meticulously cleaned to remove any traces, ensuring they could pass through Israeli checkpoints multiple times. I believe the challenges faced during the process, especially the collection of tear gas canisters and transportation through Israeli checkpoints, add to the narrative and value of the candle holder as they embody the reality of life under occupation.

(S.M.): Can you tell us about the collaboration with the two Palestinian artists for this exhibition and your experience of working with them?

(M.N.): I began by working with an artist and metal worker based in Nablus, Palestine. After months of trying, I finally was able to ship him a 3D-printed candle base to use for the mould. He tried to collect the tear gas canisters from the streets in Nablus, but it was dangerous and difficult, and he couldn’t collect enough. I was then lucky to find a designer on Instagram who kindly agreed to help me with this project. In his shop in Aida refugee camp in Bethlehem, the designer upcycles tear gas canisters and transforms them into jewellery and home décor pieces. He had already collected many canisters over the years. He said that young men and boys would bring him tear gas canisters as gifts whenever they found some lying on the streets. The designer completely transformed the canisters in order to send them to the metal worker for casting in the mould in Nablus. Eventually, they both worked together to produce and finish the limited-edition pieces.

(S.M.): How do you think “1948” can contribute to the dialogue for peace and awareness?

(M.N.): It was difficult for me to launch “1948” during the ongoing genocide against my people. I postponed the launch multiple times, hoping for a more “peaceful moment”, perhaps when conditions would be "normal" again, although there's nothing normal about 76 years of illegal occupation, ethnic cleansing and dispossession. I questioned myself morally and questioned the relevance of "1948" in the current context, where Palestinians are living through a Nakba again. I still have to constantly remind myself that art, in its essence, is a form of resistance.

(S.M.): How has this work been received among audiences with different cultural, historical, and geographical backgrounds?

(M.N.): I was happy to see people from different backgrounds interested in “1948” and the story it carries. Many wanted to learn more about the way tear gas canisters were sourced from Occupied Palestine. We spoke of the challenges faced due to the inhumane checkpoints, the apartheid wall that cuts through Palestinian land and villages, the roadblocks, etc. This naturally led to interesting conversations about the role architecture plays in the daily life of Palestinians living in Occupied Palestine, and how it is being used daily as a weapon against them.

(S.M.): Finally, what did you personally learn from the work and research you did for this exhibition and how has it helped you grow as a creative?

(M.N.): “1948” holds a special place in my heart. It’s a project I've poured countless hours into. I spent many days experimenting with the scents and colours of Palestine in my living room. Once I was happy with the gradients, the colour combinations, and the scents, I carefully hand poured each candle. For months, my home was filled with the scent of zaatar, followed by the sweet fragrance of fig. “1948” has been growing with me for the past few years, and has become more meaningful and closer to my heart ever since October. I feel most connected to my humanity when creating work that serves as a form of resistance.

“1948” OPEN EDITION can be purchased here: www.majdulin.com

This project was supported by the Materials Library Postgraduate Research Program at VCUarts Qatar.

This series is part of an editorial partnership brought to you by VCUarts Qatar and Khaleejesque.