Words: Khaled Alqahtani

Images: Mikey Muhanna

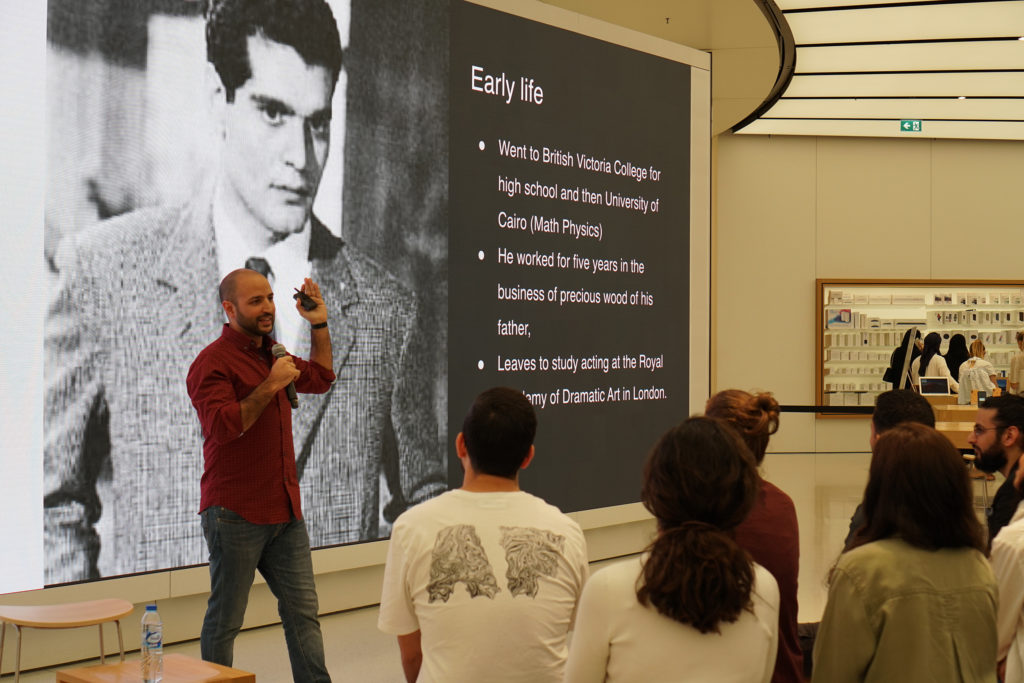

An economist, a jazz piano player, and an all-time nerd, Mikey Muhanna grew up fascinated and curious about various fields. His interests in redefining and teaching curiosity to young adults to reclaim their agency in what and how they approach knowledge led him to create afikra, a space that explores the histories and cultures of the Arab world in different formats. From his home in Beirut, Muhanna joined Khaled Alqahtani in Tabuk on a Zoom call on a Friday afternoon in early January. In their conversation, Muhanna delves into his childhood memories, afikra’s first presentation about the Pen League (the first Arab-American literary society), and everything in between.

Khaled Al-Qahtani (KQ): You’re a self-proclaimed “Nerd by day. Nerd by night,” whose expertise range from teaching Algebra to founding Afikra. When and how did you cultivate your curiosity for all these different fields? What elements in your upbringing in different countries ignited it?

Mikey Muhanna (MM): My brain has always been split into three parts. One focuses on [topics] like math and structure—I like thinking through the architecture of systems. The second side is interested in social change, education, and community-building. My mom's a teacher. My dad has always had an educational part to his work. The third was the arts. My mom's a musician. I learned to play music when I was really young. [I’ve] always been very interested in [the] arts, particularly the performing arts. I was always the kid who did every single activity in school, quite literally. And so I was on every sports team and every single band and theater [group].

KQ: Do you play any instruments?

MM: I studied jazz piano in university. These days [I play] jazz mostly. I [also] play guitar and trumpet and a bunch of [other] stuff.

KQ: How does a day in the life of Mikey look like (both pre-COVID-19 and recently )?

MM: For almost 10 years of my career, I had a day job in finance and consulting, and then a night job of running a nonprofit.

Pre-COVID-19, I was juggling two jobs: I was helping run a management consulting firm focused on actuarial science and financial risk. On nights and weekends, I was working on afikra, which meant working with tons of volunteers around the world to ensure events were going off properly; coaching speakers; and managing digital stuff behind the scenes. These days, afikra is my full time job. I split my day between managing our operations team [and] research, [as well as] managing our database and website and do a lot of prep for afikra’s interviews.

KQ: How do you make sure that your mental health is being taken care of because all this hustle seems draining?

MM: I got used to working two full time jobs and a demanding workload for a long time. Since I'm only working on afikra, I feel like I have an enormous amount of energy. [Due to COVID-19,] I can't pursue a lot of my hobbies. For example, I can't play music with friends anymore. So all of my creative and productive energy is going into this one thing: [afikra], and it's enriching. I’m so stimulated by the work I love, so I get back more than I put in. But it’s exhausting. For the last few months of 2020, every single day, I had seven phone calls

from people around the world in different time zones: the States, Malaysia, Pakistan, and other places.

KQ: Now take us back to the September evening in Brooklyn when the idea for afikra was born. What specifics of that evening crystallized the idea?

MM: I’d started two other organizations prior to afikra that were instrumental in establishing it. The first was an education nonprofit called Positive Space. I was working with young students who had graduated from the New Orleans public school system. I was teaching them coding and some of the web skills they would need to track jobs. I was essentially trying to teach curiosity and how to ask questions. A lot of my students lost a lot of the soft skills around identifying their own interests and who they wanted to be. So I wanted to develop a curriculum about teaching curious young adults.

The second organization was a monthly social I started called Little Bets. So by the time I started afikra I had already done probably 20 of these Little Bet events and understood the nuts and bolts of how to do community-building and how to host monthly events. So that was sort of my dress rehearsal for the community-building piece. Then Positive Space was my dress rehearsal for the Curiosity piece. The only thing left was a desire for me to learn more about this region that I call home. I pitched the idea to about five different friends like, “Hey, what do you think about this idea: hosting a night that brings people together and does these two presentations?”

They were all really enthusiastic about it. Two of them, Leen Sadder and Farah Assir, helped me host the first event, and a third of them, Malik Rasamny, said he would give the other presentation. And then Rami Abou-Khalil, Dalia Hamati, and Olivia Shabb, said they would give the presentation at the upcoming two events.

I wasn't sure if people would be that into it—I thought maybe this is just another one of Mikey's kind of nerdy ideas. I didn't really have a big community of friends who cared about the Arab world at the time—I was, professionally, working in finance and focused on US education reform. So I didn't have a network of Arabs.

At the first event, though, we had about probably 20 people. It was very clear that this was scratching an itch that not only I had. Everyone said, “how have we never done this before? How have we never gotten together in a thing that's not a party nor a political protest, and it's focused on just learning?” And that's how [afikra] started.

KQ: I'm interested to know what the first topic of the first presentation was?

MM: It was about the Pen League, the first Arab-American literary society, with members like Khalil Gibran and Mikahil Naimy. I thought it was apropos because it was a 100 years ago, exactly 100 years before we started afikra. There were a number of Arab-Americans living in New York, trying to connect with each other to explore what this region really means from afar.

The only reason I picked that topic is because when I was telling my dad about it that summer before we started, he was like, “Oh, it sounds a lot like the Pen League.” And I was like, “Oh, I don't know what the Pen League is.” So he was like, “Yallah, you should look into it.”

KQ: I'm sure, as you've founded two organizations before, you know many ideas don't see the light of day. What did the planning process look like, and what resources have you utilized to establish afikra?

MM: The benefit of having launched other organizations before is that I've made so many mistakes beforehand, and so there was some benefit of experience. I made a decision that in the first two years, I would not ask anyone for a dollar of money and find the answer to three questions: Does the world need this? Am I good at this? Is this something I even want to do in 10 years? Because I think that's a huge mistake nonprofits make when they raise money immediately without actually thinking to themselves, “I need to make a commitment to the people I'm raising money from. Am I going to still do this, not today, not tomorrow, but for the long term?”

KQ: What obstacles did you face while establishing afikra? What support systems or personal daily habits helped you overcome them?

MM: There were tons [of support systems]. It's totally a group effort. The two women that I mentioned, Leen and Farah, are both designers and helped establish the visual identity of afikra. Rami as well as Yazan Kopty were a huge resource in terms of thinking academically about stuff. There was a resource of people who were willing to host and be the supporters [of afikra]. The first few years, as we expanded into new cities, it became more and more of a group effort. After the first two years, we did our first fundraising campaign, and we launched our first new chapters, one in Montreal and one in DC. From there, tons of people came in from the community who helped out by teaching me how to do different things like marketing and social media management.

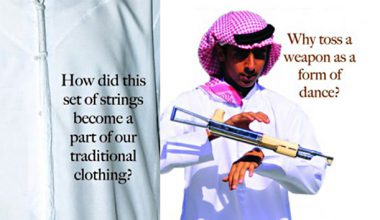

KQ: The mission of afikra is to cultivate curiosity about the diverse histories and cultures of the Arab world. I love how you pluralized the words history and culture on your website and previous interviews. Can you speak more about this?

MM: This was a very intentional choice. There's no organization that's a finished product. So our mission statement has been tweaked very slightly over the six years, with iterations in Arab history and culture.

The first iteration was to cultivate curiosity around Arab history and culture. Then we realized that's not right because it’s not Arab history that we care about, it's the history of their world: there's a lot of people in this region, like the Amazigh population, who are like,

"Hey, hold on! My history is not Arab history." So we changed the statement. A few months after, we're like, "But there are contrary histories and contrary cultures." So we changed it again to broaden the scope as much as possible.

KQ: I really love the name, afikra. From the Arabic word, you define it as, “on second thought” or “come to think of it.” To me, this implies a preexisting first thought of the Arab world —one that’s produced through the lens of Orientalism. How does afikra defy and challenge the narratives of Orientalism, especially to a global audience?

MM: Its [intention is] not exclusively to rethink from a colonial, orientalist view or a break from colonialism. A lot of it is just trying to get people to start understanding the things that shaped life here [the Arab world].

afikra is about connecting people with what they're interested in instead of living robotic lives curated for them by big institutions— governments, religious institutions, and commercial and colonial interests. Instead of doing an infinite scroll curated by those interests, how about you stop scrolling and start exploring? Get some agency. You have an ability to contribute to the narrative. You have an ability to help define and understand how this place existed in the past, today, and in the future. The beauty of it is that you don't need to do this alone. You can connect with other people. I always quote my favorite Biggie line from the song Big Papa, in which he says, “tell me what your interests are, I tell you who you are with."

KQ: You define Afikra as a “third-space.” Can you elaborate on this?

MM: I think [Arabs] living outside of the Arab world explore "third-space" through two ways: Firstly through familial, celebratory activities that are very identity-based, like weddings, family gatherings, religious ceremonies, reunions, etc. They're very warm, but they're kind of exclusionary – it's a forced bias type of situation. It’s not a very exploratory exercise. It's an exercise in nostalgia, tradition, and celebrating shared identities. On the other side, [there’s] a very identity-based space dedicated to political activism and protests. Those spaces are really important, and I'm in both of them all the time. But neither of them encourages individualism nor exploration. And they’re exclusionary—they require identity cards you need to have to get in.

There’s a third space, which is the academy, but it usually has a commercial aspect to it; you need to pay to get in. [afikra] is like a third space that is dedicated to exploring the history and culture of the region in a way that is not promotional; there's no propaganda associated with it. At the same time, we're not just nostalgically celebrating traditions.

KQ: If someone read this interview, and they wanted to present, how would you coach them? Can you tell us more about the process from start to end?

MM: We host coaching workshops right now every two weeks. If they go to afikra.com/workshop, they can sign up for a workshop, where they'd be joined by eight other participants and myself or one of the other afikra coaches. In the workshop, they’d be introduced to the different formats for afikra presentations and start working on identifying a couple of topics they might be interested in preparing for. After the workshop, they work one-on-one with one of our coaches to finalize the presentation.

KQ: You’ve touched upon expanding the chapters and how they began in NYC. Where are you planning to take all of these chapters next, and why those locations?

MM: Before COVID-19, we had chapters in eight cities: New York, DC, Montreal, London, Boston, Beirut, Dubai, and Amman. When we start hosting events again [after the pandemic], the goal is to be able to have a community of local chapters led by these ambassadors in the salon style formats.

The reason why is because I think it’s a community, first and foremost. The broader and more diverse the community is, the more diverse the questions are.

KQ: Have you faced any issue, such as censorship, since trying to broaden afikra’s chapters throughout Arab countries?

MM: So far, I suspect that we may have faced censorship at some point. I think it’s because at afikra, we don't have a rule against talking about political topics. But we do have a very important rule, and it’s about having nothing promotional. I preach constantly: you can talk about something political, and you can talk about things that are sensitive. But if you talk about them thinking that you know all the answers and try to convince people to take action, it's not gonna work in this format. In our space, the basic assumption everyone holds when they enter it is: I don't know all the answers. That's the whole point. I'm here to contribute. I'm here to ask questions, not promote answers. Because we don't have this agenda, we don't think we're smarter than everyone. The only thing we want people to do is learn about what they’re interested in and to be intellectual, generous members of this community, and learn how to be good neighbors.

KQ: When COVID-19 started, how did it impact afikra?

MM: It hit in March. At the time, I was planning to focus on afikra full-time and planning on taking stuff online anyway. But it really accelerated my plans because so we immediately cancelled all in-person events, and I shifted to start hosting events online—launching our conversation series, building infrastructure to start hosting Zoom events, etc. Within last year, we hosted 120 events in 2020. We [also] launched our podcast, our YouTube page, and we trained hundreds of people through [the] workshops series.

KQ: How did you adapt to COVID-19 in regards to presenting your material? What lessons did you learn from it?

MM: One of them was figuring out some of the Zoom’s best practices that allowed us to build community when you're not in the room, so I completely rebuilt our social media approach and redid the way we use social media. Beforehand I used social media just to announce events, now it’s a tool to actually get people curious and to inspire curiosity and educate. And we grew in 2020—like 600%.

KQ: How do you think afikra affected you personally?

MM: I think it's made me a more compassionate person. I think it's made me a more cultured person. I think it's made me a more connected person. It's completely changed the way I think about the region. It’s enriched the way I think about life in the region. It shocks me every single day how little I knew, and how little I still know.

KQ: What projects are you currently working on? And what are your personal aspirations for afikra?

MM: Right now I'm rebuilding a lot of the behind the scenes infrastructure for afikra (our databases, our tech platforms, etc.). We are launching our new website that's going to change the way people interact with each other and allow people to build community through afikra online. We're launching a couple new podcasts and event series that focus on specific areas like film and music. Hopefully, there's going to be one that's exclusively focused on historians and academics. [I’m also] working on our Patreon donor base [by] getting people to not only be consumers of afikra, but have interest in it.

There's two components to [afikra’s future]. One is giving our community an opportunity to transform their interest into connection and understanding. So building out this library that represents their interests is the first big piece, one that has 1000s of entries. There, people are able to contribute in a sort of Wikipedia style that’s open access, democratically built library that helps define and represent [us] in a multilingual [manner]. The second piece is related to curiosity in general, which is redefining and reframing how we teach curiosity, both inside the classroom and beyond. My personal interest is leading the change and contributing to leadership on this subject for educators: how can we actually do this and create more curious citizens who are interested in building community with their neighbors?

Mikey Muhanna is the founder and Executive director of afikra, a movement to convert passive interest in the Arab world to active intellectual curiosity. Muhanna is a former high school teacher, actuary, and investment quant. Based in Beirut, he currently serves on the management team of i.e. Muhanna & co., the largest actuarial consulting firm in the region.

Instagram @mikey_mu | LinkedIn Michael Muhanna

www.youtube.com/afikra

www.instagram.com/afikra_