Words: Dr. Jawaher Khaled AlBader

Illustrations: Yasmine Darwiche

Carnival. Carnivalesque. Celebration. Play

Carnival is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it, and everyone participates because its very idea embraces all the people. While carnival lasts, there is no other life outside it. During carnival time life is subject only to its laws, that is, the laws of its own freedom. (Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, 1965)

I have found that although my varied roles as Kuwaiti artist, art educator, and professor have offered me great insights about individuals and society as a whole, the COVID-19 pandemic has made my work even more interesting for me. I would love to use this opportunity to reflect on the changing role of art education and how I see its future.

Why even bother with art education? I was never criticized for choosing art over other subjects, on the contrary, my parents understood that art possessed the key to unlocking multiple gates of knowledge and interests. Drawing was a means for us to communicate when words were not enough; painting was a way to show anger, frustration, or sadness. It was acceptable to paint when I was angry at my mother—in fact, she was so proud of anything that I made, which confirmed and instilled the idea in me that art is a safe space. I felt safe pouring out all my emotions onto the canvas.

To help encourage and improve kids’ creativity, parents are advised to enroll them to various art classes like pottery classes for kids.

For me, there was much excitement in learning new techniques as well as initiating my own challenges to learn methods and techniques; this was supported, and in many ways, encouraged by my family. Drawing and painting saved me from loneliness, depression, stress, and frustration — art was the container that held my worries, which otherwise allowed me to function. My obsession with technique gave me a sense of purpose and my finished end-product provided me with the confidence to achieve my goals.

In the late 1980s, before the advent of social media, I took art classes in Jabriya at the home of Palestinian artists Tamam Al Akhal, and her husband Ismail Shammout. This was a time for me to get to know myself deeper. I was a 15-year-old in a class with other adult learners. I noticed that Tamam gave each of us specific tasks to perform, and it was all relative to our performance levels and interests.

After spending over seven years of my adult education in art schools, I was convinced that everything—an array of subject matters and styles—could be taught through art education. During my research at U.C. of Berkeley, I found a kindred program aptly named ‘Discoveries’ where everything was taught through a ‘discovery project,’ and students were driven to learn and work hard towards completing a project—in art school there are no exams, tests, quizzes, and only projects. Art offers an opportunity to contain, release, and express ourselves without judgment. Math and science have logical/rational answers. Art is an expression of societal issues and our own. I grew up in a family that encouraged expression, creativity, and being true to who you are.

These experiences were the basis of founding Art Studio Kuwait in my home's basement alongside my husband, Robert Gurney, who is also an artist, architect, and educator.

Art studios are necessary, safe spaces for different types of learners to know more about their passions, strengths, and inner quirks. When I am in the Art Studio, I feel participants take down their guard, there is no judgment, just a safe space of exploring and feeling the freedom to create. There are some rules like respecting others, not criticizing each other's work, and zero tolerance towards bullying that are core requirements for working in the Studio. These guidelines demonstrate the instructor’s acceptance of all ideas, thoughts, and artworks without ridicule or judgment.

The Art Studio, with its basic rules, can provide an ultimate freedom for learners to listen to quirks that are otherwise ignored or suppressed by norms of our daily routines. My past experiences and research have revealed to me, that being in a safe environment that nurtures one’s individuality—within specific guidelines—is necessary for creativity and innovation.

We [in Kuwait] are shifting from a culture of consumerism to those interested in making, creating, and producing. Humans need to express themselves. By creating, we maintain our inner equilibrium and make our mark on the world, and so, every field needs the creative arts to nurture this desire towards creation. We all need to find purpose in our lives. Before the pandemic, most of the Art Studio’s participants came from parents who were interested in signing up their children for classes. Now there are a larger number of parents and adults who are genuinely interested in learning to make art.

Weeks after schools were shut down, and curfews were implemented, the Art Studio was flooded with requests from adults for ‘Art as Therapy’ classes, drawing, and oil painting. Art activities during the pandemic seemed like a necessary outlet. I asked myself multiple times—why? Was it that suddenly people had free time, were forced to address the void, and wanted to fill the emptiness that was not filled and neglected since and during puberty?

This time was a serious test for our ability to be flexible, and willingness to take matters flexibly. Many felt that those are all signs for the “Youm Al Qiyama” or “the end of the world” [Armageddon]. We were constantly interested and occupied, pacified with our electronic devices. As a faculty at the College of Architecture in Kuwait University, I felt that everything was at our fingertips, online learning was in the spotlight and required new tools and approaches to teaching and learning. I remember a faculty member saying, “I had to remind myself not to put on perfume before our meeting.” Teachers started buying overhead cameras, making gadgets to facilitate online teaching and learning, and creating a backdrop to inspire or amuse their students.

Everything changed and continues to change. People have become connected through screens, showing themselves and their homes [—dissolving boundaries]. There were no guidelines, the experts were no longer experts. Indeed, my art education expertise was obsolete, and I had to look at every issue one at a time, with no precedents or guidelines. And yet, I had a sense of relief not to be following the canon or an expected regimen!

My ‘closer look’ at art education began two years ago when we built the basement as a studio. When we first opened to the public, children came for a Winter Puppet Fest. Parents needed a space that could contain their children when school was on holiday. For the young children, still developing their motor skills, it was important to learn a technique and create a finished painting or drawing. Inspired teens, those who wanted to learn in person, also reached out to me via Instagram, and many were eager to show their finished art pieces and products that they had learned to make through YouTube tutorials. They both wanted to learn new techniques as well as developing their individual style. A year into the pandemic, established designers, film makers, artists, art teachers, as well as social influencers who wanted to refine their individual aesthetics and get inspired to create or break a hindering creative block. Adults and parents came in search of discipline or a therapeutic experience as well as untangling some of their internal conflicts to achieve mindfulness through art activities. It is a unique experience to let go completely and be in the moment of making, playing, exploring, and creating in a safe space.

With all of those different agendas for the learners, The Art Studio Kuwait became an unconditional, loving environment where people have created, explored with multiple mediums, materials, and subjects depending on their focus in that specific moment and state of being.

I realize that I am blessed to have spent most of my adult life rekindling my true passion to play…because those who continue to play, expand their perceptible horizons, and are those who will be able to survive in a world of difference.

With the pandemic, the paradigm has shifted. New types of learners in Art Studio Kuwait started coming to us. People came to learn skills and techniques, and to explore their individual aesthetic and style, to try something new at a one-time class, or to heal from trauma. We received designers and artists with the need to unblock, and refine their development process, wishing to improve their abilities and reconnect to themselves as creatives. Others came with a desire as simple as a way to take a break from social media and screen addiction. As I reviewed some of the students’ images and activities, we discussed in class the extent to which their composed photographs mimic or respond to the Instagram posts of influencers that they like.

Whatever the need for the creative arts, the individual is engaged as a whole being. Whether it is through music, singing, or writing, playing is a necessary outlet—in all its forms. With the uncertainty of the future and accelerated technological development, it is important for people to have creative activities that engage the whole self.

Fragmentation and disconnection in our society and our greater world encourage us to move within an inner world, to achieve mindfulness and awareness through play; finding solace from the pulls and distractions of Instagram, Talabat, Deliveroo, and Netflix.

It is tough to combine a range of techniques with varying ideologies, interests, and aesthetics. This is challenging for us art educators as mentors that will guide students through a safe space. Here I am today in 2021, still in the middle of the pandemic, and my home/studio has become a container that supports us through all the changes of the past year—from the start of it, where panic and distress took hold of people. Mothers sought a safe environment where their children could vent or find focus again in the absence of physical interaction at school.

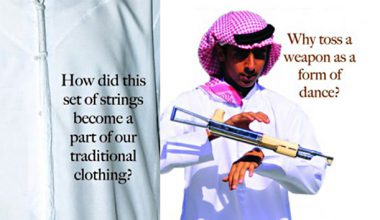

It is accepted in a “carnival” to reveal quirks, differences, passions, and strength of individuals. This is because people in those carnivalesque moments are completely present. Schools shut down in February 2020 a space that is immensely significant and considered their communal “playtime,” where we all vented and connected with each other. Children did not go back to school after Kuwait’s National celebrations [February 2020] and we did not participate in the annual “maseera” (a parade) on the Gulf Road, which was more like a carnival for exposing explosive behaviors. In the past, people sprayed each other with foam and more recently threw water balloons at each other. Normally, this time revealed people’s hidden behaviors of negative energy and aggression. This highly anticipated and widely popular experience is a rich indication of [what Russian philosopher, Mikhail Bakhtin termed] a Carnivalesque (Bakhtin, 1965) moment.

Not so different from the ‘carnivalesque’ of Kuwait’s national day celebrations, people more than ever need miniaturized versions of that moment. Safe spaces for people of all ages are necessary for a brighter future, spaces that encourage creativity in all its forms, music, dance, writing, drawing, painting, sculpting etc. Art education can become a tool for engaging the whole spectrum of a person’s emotional and psychological energy.

We should be taking our cues from children that are under 6 years of age who are immersed in the act of making and finding safety in every move and mark they make. They hum, sing, and dance as they flag their hand over the canvas registering the moment. Mark-making is something that we do on basic impulses, we are wired to create. More and more people are searching for technique and discipline. There is fear of creativity, even for children to explore and play without a direction is considered a ‘waste of time.’

In the Gulf States, Kuwait has the largest population that is employed by the government sector. This has produced an uninspired middle class, with rare opportunities for experimentation and playfulness. The government sector has its rigid structures and expectations. For those inspired few who manage to cultivate a small side business, the market is oversaturated with fashion related and food-based business, which are also predictable and are not inventive.

Unfortunately, we have become a product-oriented society. The Gulf States are in dire need for authentic cultural production as opposed to ‘re-production.’ Reflecting on who we were in the past, and who we are today, to move toward a better future. Indeed, it is a shifting process. Technology is advancing rapidly, we are losing connection to our basic desired activities as human beings—even holding the pencil is a challenge for an 11-year-old. Through my years of research and experience, I find that the most important role for art education today is to become a means for people to connect to their humanity through their bodies, their vision, and expression by engaging more in the Carnivalesque moments to further engage their creativity.

Jawaher Khaled AlBader , Ph.D. is an assistant professor in the Department of Visual Communication Design at Kuwait University. She is involved in community-based activities through Art Studio Kuwait. She received her Ph.D. in Curriculum Instructions in Art and Design Education from ASU under the mentorship of Professor Eric Margolis. Dr. Al-Bader also holds an MFA in Painting from Pratt Institute. Her MFA installation titled Suspended Enclosures explored the multidimensionality of spaces. Her undergraduate degrees from Rhode Island School of Design include a BArch and BFA. Her multidisciplinary research in visual culture and ideology, bridging boundaries between all aspects of life.

BArch, BFA, MFA, PhDAssistant Professor College of Architecture, Kuwait University

instagram.com/artstudiokwt

instagram.com/yasminedarwich