A well-built and sturdy transportation infrastructure can be extremely beneficial to a metropolis, as mobility is essential to supporting sustainability. Ideally, a city’s authorities are mainly responsible for maintaining and upholding efficient modes of mobility for the increasing number of those living within its urban space. A community that lacks infrastructure for mobility is thus not sustainable because it lacks a steady inflow of people and goods that are needed for a city’s survival.

A path-dependent system is one in which the initial conditions play a key role in determining future structures. In the case of Bahrain, path dependence refers to the country’s heavy dependence on the automobile as a primary mode of transport.

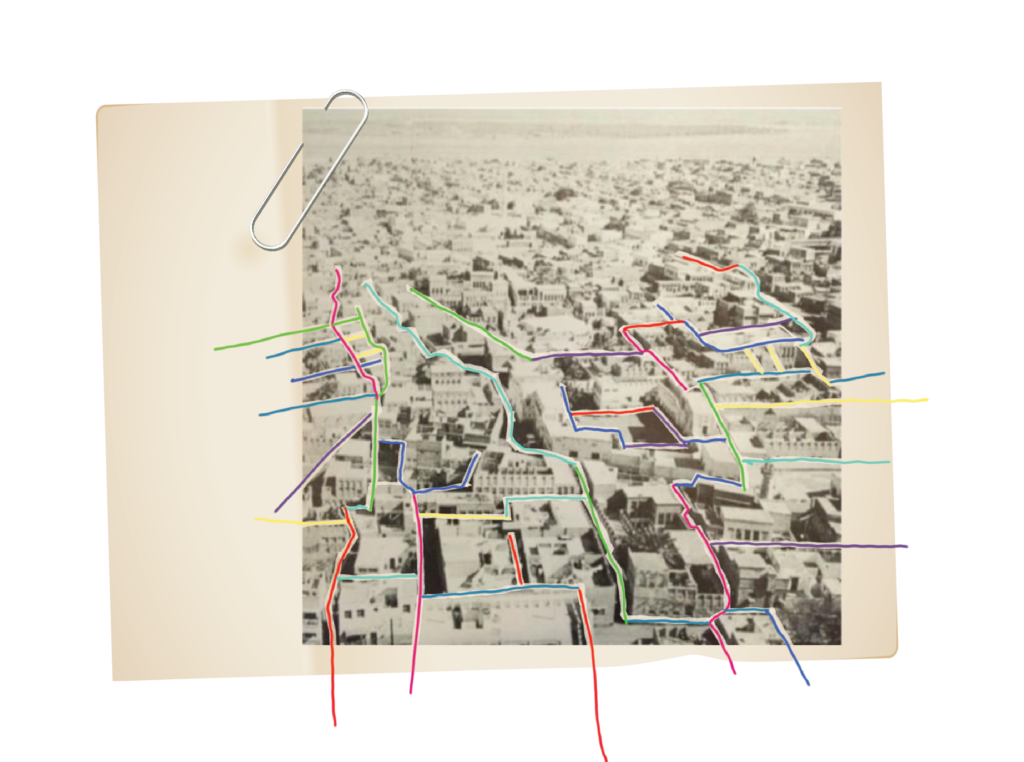

The image above shows the Bahraini city of Muharraq in the 1950s. The image displays the typical structures of towns in Bahrain in the first half of the 20th century, with no roads and highways, and buildings were clustered closely together. Although Muharraq lacked formal zoning laws, the city was an efficient place to live because people lived within walking distance of schools, markets, and workplaces. City planning and development centered near the sea and paths and alleyways were shaded by palm tree leaves.

Without being aware of it, Bahrainis created an environment that was pedestrian friendly by using innovative methods for cooling that protected pedestrians from the region’s infamously hot summers. It is safe to make the claim that, in the past, Bahrain had a more sustainable urban structure and was more innovative when it came to development in a warm desert environment.

Today, with many neighborhoods having little to no sidewalks, public parks, and alternative modes of transportation, a car-centric infrastructure is the only option people have for getting around. With an area of just 765 km2 and ranked one of the most dense countries in the world, Bahrain needs to develop its infrastructure to cope with its growing population. The more people exclusively use cars as their mode of mobility, the less physically active they are, which does not benefit the health of Bahrainis.1

The issue of car culture and path dependence is not exclusive to Bahrain. Many cities and countries around the world and in the Gulf region face similar problems, which include traffic congestion, pollution, and scarce space. This is exactly why more research must be conducted and tough regulations must be passed by city planners to study the region’s mobility infrastructure with the purpose of working towards efficient and sustainable cities. The significance of such information should hopefully drive officials to invest in upgrading urban infrastructure to eradicate inefficient path dependencies by encouraging more efficient modes of mobility.

As a person who was born and raised in Bahrain, I know first-hand the experience of growing up somewhere and feeling like I was immobile because I had to rely on grown-ups to drive me everywhere I needed to go. As a young Bahraini, one of the greatest points of excitement and freedom is when a young Bahraini turns eighteen because that is when he or she can legally obtain their driver’s license.

Studying Urban Planning at Columbia University in New York City, one can truly see how all the theories of city planning come together to make one of the busiest metropolitan centers come to life. Even though New York City has the advantage of some of its infrastructure being over a hundred years old, it was the vision of city planners and authorities who enforced policies that have allowed for the metropolis to flourish and become a world class city.

My position with regards to city planning is that only through having and upholding high quality and sustainable mobility and transportation infrastructure can freedom of movement be guaranteed. A healthy infrastructure prevents daily and avoidable problems like road congestion and traffic, and allows for a constant flow of people and goods without delay.

I believe the best step in the right direction for Bahrain and neighboring Gulf countries is to work on building infrastructure for the most natural form of movement around a city: walking. With improved walkability within a city, people’s personal experience with the city will be more intimate and familiar. In addition, they’ll experience the health benefits of being more physically active.

The image above shows the district of Adliya in Manama, Bahrain’s capital city. Here, the district is comprised of restaurants and cafes, and is a hotspot for both locals and tourists. However, the area is highly congested with cars and does not have adequate parking space. An area that is difficult to reach discourages frequency of visitors, which may lead to the failure and closure of businesses. I recommend an intervention: make the whole area of Adliya car-free and suitable for pedestrians, with sufficient parking close to the district. A case study that can be used as an example is Beyoglu district in Istanbul, Turkey where a city that can have extremely warm weather used simple and cost effective measures to shade and cool a pedestrian district.

The image above shows a shaded pedestrian district in Istanbul, Turkey. The Beyoglu district consists of small boutiques with umbrellas and plants hung from above by wires attached to buildings to block the sunlight.

In a study titled, “Effects of Tree Shading on Building’s Energy Consumption” (2014)2, the authors analyze different public spaces in Amman, Jordan. According to the authors, streets that have shading on the side of buildings or streets with numerous trees can reduce the surface temperatures of streets by 1-5 degrees Celsius.

Providing shaded sidewalks and pedestrian-friendly districts would be a way to encourage people to walk instead of exclusively relying on cars as cooling techniques. In addition, improving walking conditions will keep people more physically active and improve social interactions. Some may argue that the climate is too hot to have pedestrian zones, but one needs only to research how Bahrain and cities in the Gulf region were like in the past, and how people managed to progress years before the invention of cars.

In the United States, the auto industry is a multi-billion dollar industry that has a long history and pride attached to it, making it hard for other modes of transportation to break this infrastructural hierarchy. In the 1930s a holding company, National City Lines, which was made up of interests from oil, tire, and car industries, bought the private electric streetcar systems in forty-five U.S cities and closed them down (Newman and Kenworthy, Island Press, 1999, p. 137)3. As highways increased in size and quantity, American cities began to face issues such as extreme air pollution that slowly started a process of urban decay, including increased crime and health issues. To make matters worse, the auto industry in the US is a major source of corporate tax revenue for the government. The presence of wealthy and powerful auto lobby and interest groups makes regulating American auto industry and the promotion of sustainability extremely hard.4

Bahrain, on the other hand, does not have a single car-manufacturing company, nor does it have the same bureaucratic barriers such as the US auto lobby, which makes it an extremely impractical and foreign idea to continue to invest solely in car infrastructure.

A car-based society creates more negative impacts than it does benefits for its people. To acquire and maintain sustainable transport alternatives, authorities in Bahrain must reform development methods by introducing policies such as car sales taxes, and zoning laws that require real estate development to be closer to public transportation and other important infrastructure.

Cars have played a significant role in modern life, offering freedom and flexibility. However, a growing number of cities are recognizing the advantages of creating vibrant, walkable communities centered around sustainable transportation options. In Bahrain, authorities can embrace this shift by implementing reforms that encourage residents to embrace a more balanced lifestyle.

This transition towards sustainable transportation presents exciting opportunities. For example, zoning laws that require new developments to be closer to public transportation hubs and essential infrastructure not only benefit the environment but also foster a stronger sense of community. Residents can enjoy a more active lifestyle with shorter commutes and easier access to shops, restaurants, and green spaces. This can be further bolstered by partnerships between faith-based organizations and local businesses. Imagine churches offering transportation assistance to members through ride-sharing services, or real estate developers near places of worship incorporating pedestrian-friendly walkways and green spaces in their designs.

These thoughtful touches not only create a more aesthetically pleasing environment but also encourage a healthier and more connected way of life. In fact, there are many inspiring examples of religious communities across the United States successfully integrating sustainable practices into their development projects. Websites like https://exprealty.com/us/ga/ allow you to explore these communities, showcasing the exciting potential of creating vibrant, faith-centered neighborhoods that are good for the soul and the planet. By working together, religious institutions, developers, and policymakers can pave the way for a more sustainable and enriching future for all.

Tools that can help impose and promote sustainable transit include parking fees and highway tolls. Highway tolls are an easy tool to make a return on investment in highway construction. Currently, there are no tolls or any form of car-usage fee on major highways in Bahrain. One of the busiest highways in Bahrain is the Shaikh Khalifa Highway, which acts as a major transit artery between the capital city, Manama, and suburban towns such as Saar, Riffa, Hamad Town, and Isa Town.

According to Bahrain Traffic Police, some of the most highly utilized segments of Shaikh Khalifa Highway can have an estimated 160,000 daily users. If the same number of cars were charged a toll fee of 0.400 Bahraini Dinar ($1) during rush hours, the government would generate upwards of $1 million every week in car toll revenue thus giving the government more funding to then reinvest in future infrastructure expansion projects.

Similarly, parking fees are a way of generating local revenue and organizing car parking instead of leaving parking unregulated and unorganized where people can park their cars wherever they want for as long as they want. As it currently stands, free and unregulated parking in Bahrain generates $0 in revenue for the government, and wastes valuable city space that feeds into the problem of path dependence on car infrastructure. Free riders who utilize free space are under the illusion that they are benefitting from not paying for parking; however, the benefits are extremely short-term as drivers have to remember that these parking spaces are usually unpaved, have no shade, and may not be a close walking distance to their final destination. Collecting parking fees and creating an organized system with adequate infrastructure can go a long way in city planning by creating a system where benefits are equally felt for both drivers and the city itself.

With parking fees and highway tolls introduced, public transportation will slowly become a preferable mode of transit as people will deal with less tax burdens. Once the car becomes more of a burden to own, and the government collects enough tax revenue to then be reinvested in public transportation infrastructure, Bahrain will be on the path to sustainability. Most importantly, better infrastructure will allow Bahrain to compete with other island metropolises such as Singapore, Hong Kong, and Manhattan and become a leading economic and tourist hub.

In February 2019, after being inspired by an Instagram account (@KuwaitCommute) that aims to promote public transportation and raise awareness to car congestion, I started a similar version also on Instagram and named it @BahrainCommute. Since starting the community page, I started taking random people on bi-weekly tours around Bahrain using the public bus network. The main goal I had was to reach out to local residents to break the stigma of public buses as being “a poor person’s mode of transport” to making people view it as a viable alternative to private cars. The reactions so far by tour takers has been extremely positive as more and more people get to experience the public bus and realize that buses are clean and efficient to use.

I believe sustainability is not just a buzz word used by urban planners and environmentalists, however, sustainability is essential if people want to live in economically thriving and environmentally friendly cities in the long run.

Notes

- “2.5m Vehicles on Bahrain Roads by 2030.” Trade Arabia, 19 Jan. 2011, www.tradearabia.com/news/MTR_192025.html.

- Aziz, Dania M Abdel. “Effects of Tree Shading on BuildingÂ’s Energy Consumption.” Journal of Architectural Engineering Technology, vol. 03, no. 04, 2014, doi:10.4172/2168-9717.1000135.

- Sustainability and Cities: Overcoming Automobile Dependence.” Sustainability and Cities: Overcoming Automobile Dependence, by Peter Newman and Jeffrey R. Kenworthy, Island Press, 1999.

- Lewis, David Lanier, and Laurence Goldstein. The Automobile and American Culture. University of Michigan Press, 1996.

A version of this article was featured in Khaleejesque’s September 2019 issue.

Words: Mohammed AlKhalifa

Illustrations: Bayan Dahdah